1

/

of

10

HTM Apiary

Monastery Raw Honey

Regular price

$18.00

Regular price

Sale price

$18.00

Unit price

/

per

Shipping calculated at checkout.

Share

Just Arrived!

-

UFOs: The Demonic Connection

Regular price $10.00Regular priceUnit price / per -

Sold out

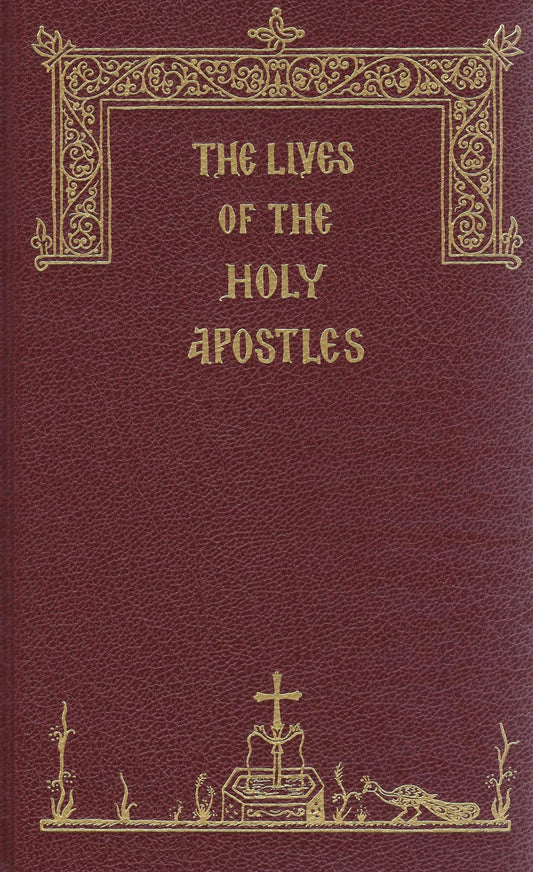

Sold outThe Lives of the Holy Apostles

Regular price $26.00Regular priceUnit price / per -

Healing the Soul: Saint Porphyrios as a Model for Our Lives

Regular price $17.00Regular priceUnit price / per -

The Dead Are in Great Need of Our Help

Regular price $4.00Regular priceUnit price / per -

St. John of Kronstadt Mounted Jordanville Icon

Regular price From $25.00Regular priceUnit price / per -

Hand Censer 08

Regular price From $16.50Regular priceUnit price / per -

Enduring Love: Laying Christian Foundations for Marriage

Regular price $30.00Regular priceUnit price / per -

Saint Silouan, the Athonite

Regular price $33.00Regular priceUnit price / per -

The Synaxarion: The Lives of the Saints of the Orthodox Church (Complete 7 Volume Set)

Regular price $350.00Regular priceUnit price / per -

Sts. Sophia and Daughters Mounted Jordanville Icon

Regular price From $25.00Regular priceUnit price / per$40.00Sale price From $25.00Sale -

Saints of England's Golden Age

Regular price $13.95Regular priceUnit price / per -

A Child’s Guide to Prayer

Regular price $19.25Regular priceUnit price / per -

Hand Censer 24

Regular price From $18.50Regular priceUnit price / per -

Current Issues in the Orthodox Church: Book 1

Regular price $10.00Regular priceUnit price / per -

Meditations for Holy Week: Dying and Rising with Christ

Regular price $13.50Regular priceUnit price / per -

St. John the Baptist Mounted Jordanville Icon

Regular price From $25.00Regular priceUnit price / per -

Old-Rite Orthodox Prayer Book

Regular price $35.00Regular priceUnit price / per -

Thirty Steps to Heaven: The Ladder of Divine Ascent for All Walks of Life

Regular price $18.95Regular priceUnit price / per -

Meditations for Great Lent: Reflections on the Triodion

Regular price $9.95Regular priceUnit price / per -

Commemoration Book - Our Lord Jesus Christ

Regular price $7.50Regular priceUnit price / per -

Candle Holder 05

Regular price $19.50Regular priceUnit price / per -

Explanation of James

Regular price $17.30Regular priceUnit price / per -

Violet - Jordanville Incense

Regular price From $4.00Regular priceUnit price / per$6.00Sale price From $4.00Sale -

Explanation of Hebrews

Regular price $21.95Regular priceUnit price / per -

Prosphora Dough Cutting 02

Regular price $30.00Regular priceUnit price / per

Discounted Items

-

Calendar of Liturgical Seasons 2025 (Julian version, old calendar)

Regular price $6.00Regular priceUnit price / per$24.00Sale price $6.00Sold out -

Sold out

Sold outSt. Nicholas Icon Ornament 1

Regular price $2.25Regular priceUnit price / per$9.00Sale price $2.25Sold out -

Sold out

Sold outChrist Pantocrator Icon Ornament 1

Regular price $2.25Regular priceUnit price / per$9.00Sale price $2.25Sold out -

Air freshener for car - Crown

Regular price $7.50Regular priceUnit price / per$15.00Sale price $7.50Sale -

Jordanville Cathedral Glass Engraving

Regular price $32.00Regular priceUnit price / per -

Iconostasis with Electric Lamp: Christ and the Theotokos 1

Regular price From $26.00Regular priceUnit price / per$52.00Sale price From $26.00Sale -

St. Spyridon, Small Icon, Silver border

Regular price $6.25Regular priceUnit price / per$25.00Sale price $6.25Sold out -

St. Panteleimon, Silk Screen Icon on Wood

Regular price $19.75Regular priceUnit price / per$39.50Sale price $19.75Sold out -

Sale

SaleCeramic Lampada 03

Regular price From $11.25Regular priceUnit price / per$15.00Sale price From $11.25Sale -

St. John the Baptist, Small Icon, Silver border

Regular price $6.25Regular priceUnit price / per$25.00Sale price $6.25Sold out

Bestselling Icons

-

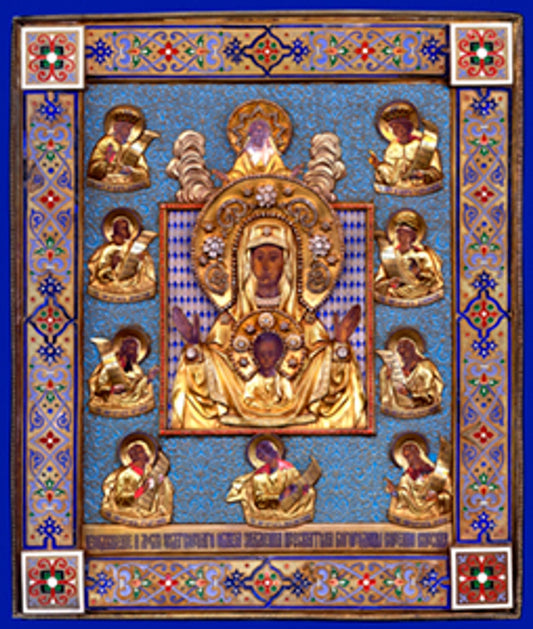

Theotokos (Iveron-Hawaii) Mounted Jordanville Icon

Regular price From $18.00Regular priceUnit price / per$40.00Sale price From $18.00Sale -

Christ (Saver of Souls) Mounted Jordanville Icon

Regular price From $25.00Regular priceUnit price / per -

Fr. Seraphim Rose Mounted Jordanville Portrait

Regular price From $25.00Regular priceUnit price / per$40.00Sale price From $25.00Sale -

Triptych for Car 03

Regular price $3.95Regular priceUnit price / per -

Royal Martyrs Mounted Jordanville Icon

Regular price From $25.00Regular priceUnit price / per -

Old Testament Holy Trinity Mounted Jordanville Icon

Regular price From $25.00Regular priceUnit price / per -

St. Mary of Egypt Mounted Jordanville Icon

Regular price From $25.00Regular priceUnit price / per -

Guardian Angel Mounted Jordanville Icon

Regular price From $25.00Regular priceUnit price / per -

St. John of San Francisco Mounted Jordanville Icon

Regular price From $25.00Regular priceUnit price / per -

St. Xenia Mounted Jordanville Icon

Regular price From $25.00Regular priceUnit price / per -

Theotokos (Kursk Root) Mounted Jordanville Icon

Regular price From $25.00Regular priceUnit price / per -

St. Seraphim of Sarov Mounted Jordanville Icon

Regular price From $25.00Regular priceUnit price / per -

Theotokos (Saver of Souls) Mounted Jordanville Icon

Regular price From $22.00Regular priceUnit price / per$25.00Sale price From $22.00Sale -

Theotokos (Iveron-Montreal) Mounted Jordanville Icon

Regular price From $18.00Regular priceUnit price / per$40.00Sale price From $18.00Sale -

New Martyrs of Russia Mounted Jordanville Icon

Regular price From $25.00Regular priceUnit price / per -

Triptych for Car 02

Regular price $3.95Regular priceUnit price / per -

St. Joseph the Hesychast Mounted Jordanville Icon

Regular price From $25.00Regular priceUnit price / per -

St. Elizabeth the New-Martyr Mounted Jordanville Icon

Regular price From $25.00Regular priceUnit price / per -

Triptych for Car 01

Regular price $4.95Regular priceUnit price / per -

St. George - Byzantine Icon

Regular price $12.00Regular priceUnit price / per -

Triptych for Car 08

Regular price $5.75Regular priceUnit price / per -

Archangel Michael Mounted Jordanville Icon

Regular price From $25.00Regular priceUnit price / per -

Russian Icon: St. Paisios of Mount Athos

Regular price $15.00Regular priceUnit price / per -

St. Paisios of Mount Athos Mounted Jordanville Icon

Regular price From $25.00Regular priceUnit price / per -

Theotokos (Of the Sign) Canvas Mounted Icon

Regular price From $38.00Regular priceUnit price / per

Baptismal Crosses, etc.

-

Wooden Pendant Cross 01

Regular price $5.00Regular priceUnit price / per$7.50Sale price $5.00Sale -

Sold out

Sold outTheotokos Necklace in Velvet Box 01

Regular price $16.00Regular priceUnit price / per$32.00Sale price $16.00Sold out -

Metallic Ring 01 - Jesus Prayer (Greek)

Regular price $9.00Regular priceUnit price / per -

Sterling Silver Cross 393

Regular price $15.00Regular priceUnit price / per -

Sterling Silver Chain 925

Regular price From $45.00Regular priceUnit price / per -

Sterling Silver Cross 541

Regular price $14.00Regular priceUnit price / per -

Sold out

Sold outWooden Baptismal Cross 18

Regular price $4.00Regular priceUnit price / per -

Sold out

Sold out -

Metallic Ring 01 - Cross

Regular price $11.00Regular priceUnit price / per -

Soldier Cross™ Sterling Silver with Blue Enamel

Regular price $74.00Regular priceUnit price / per

Prayer Ropes

-

50-Step Leather Lestovka Prayer Rope

Regular price $40.00Regular priceUnit price / per -

50-knot Prayer Rope 01

Regular price From $7.32Regular priceUnit price / per -

Black Ebony Wrist Prayer Rope with Accents

Regular price $13.00Regular priceUnit price / per -

Sold out

Sold out100-knot Black Prayer Rope 02

Regular price $12.00Regular priceUnit price / per -

Black Ebony Wrist Prayer Rope

Regular price $11.00Regular priceUnit price / per -

Black Ebony 33-Bead Prayer Rope

Regular price $15.00Regular priceUnit price / per -

Black Ebony 100-Bead Prayer Rope

Regular price $21.00Regular priceUnit price / per -

Black Ebony Finger Prayer Rope

Regular price $4.00Regular priceUnit price / per -

WW - 33 Bead Wooden Prayer Rope, Gold Cross

Regular price $6.75Regular priceUnit price / per -

Bethlehem Olive Wood 100-Bead Prayer Rope

Regular price $29.00Regular priceUnit price / per -

33-knot Prayer Rope w/ Single Bead

Regular price $18.68Regular priceUnit price / per -

33-knot Satin Prayer Rope w/ Mother of God Cross Bead

Regular price $18.00Regular priceUnit price / per -

33-knot Prayer Rope w/ Accents

Regular price $19.25Regular priceUnit price / per -

WW 100 Bead Black Wooden Prayer Rope, Metal Cross

Regular price $10.00Regular priceUnit price / per -

WW 50 Bead Wooden Prayer Rope, Antique Gold Small Metal Cross

Regular price $8.50Regular priceUnit price / per

Candles

-

7-day Vigil Candle

Regular price $4.95Regular priceUnit price / per -

2A: Bundle of Candles

Regular price $19.95Regular priceUnit price / per -

Votive Candles - Box of 6

Regular price $15.95Regular priceUnit price / per -

1B: Bundle of Candles

Regular price $19.95Regular priceUnit price / per -

3E-18: Bundle of Candles

Regular price $19.95Regular priceUnit price / per -

2B: Bundle of Candles

Regular price $19.95Regular priceUnit price / per -

Sold out

Sold outGlass for votive candles

Regular price From $2.50Regular priceUnit price / per -

3B: Bundle of Candles

Regular price $19.95Regular priceUnit price / per -

Tealights in Plastic Cups (pack of 10) (candles)

Regular price $11.95Regular priceUnit price / per -

2C: Bundle of Candles

Regular price $19.95Regular priceUnit price / per

Incense

-

Roll of 33mm Three Kings Charcoal

Regular price $3.50Regular priceUnit price / per -

Holy Cross Incense - Old Church

Regular price From $10.00Regular priceUnit price / per -

Holy Cross Incense - Byzantium

Regular price From $9.00Regular priceUnit price / per -

Box of 40mm Three Kings Charcoal

Regular price $33.00Regular priceUnit price / per -

Box of 33mm Three Kings Charcoal

Regular price $22.00Regular priceUnit price / per -

Roll of 40mm Three Kings Charcoal

Regular price $4.00Regular priceUnit price / per -

Holy Cross Incense - Catacombs

Regular price From $10.00Regular priceUnit price / per -

St. Elizabeth Incense - Sarov Forest

Regular price From $15.40Regular priceUnit price / per -

Holy Cross Incense - Damask Rose

Regular price From $10.00Regular priceUnit price / per -

Sold out

Sold outHoly Cross Incense - Bethlehem Rose

Regular price From $8.00Regular priceUnit price / per -

Ethiopian Frankincense Tears - Pure Resin Jordanville Incense

Regular price From $5.00Regular priceUnit price / per -

Ethiopian Frankincense Siftings - Pure Resin Jordanville Incense

Regular price From $3.00Regular priceUnit price / per -

Holy Cross Incense - Orange Blossom

Regular price From $8.00Regular priceUnit price / per -

Bethlehem Incense, Dochiariou Monastery

Regular price From $8.00Regular priceUnit price / per -

Hand Censer 24

Regular price From $18.50Regular priceUnit price / per -

Holy Cross Incense - Cassia

Regular price From $8.00Regular priceUnit price / per -

Frankincense & Myrrh Blend (Ethiopian) - Pure Resin Jordanville Incense

Regular price From $6.00Regular priceUnit price / per -

St. Elizabeth Incense - Jordanville

Regular price From $12.85Regular priceUnit price / per -

St. Elizabeth Incense - Damascus Rose

Regular price From $15.40Regular priceUnit price / per

Church Supplies

Upper Store

English Books

Lower Store

Russian Books

Lower Store

NaN

/

of

-Infinity