I would like to take a Protestant church's electronic sign for a starting point. The sign, with a portrait of Martin Luther to the right, inviting people to an October 31st “Reformation Day potluck.” When I stopped driving to pick up a few things from ALDI's, I tweeted:

I passed a church sign advertising a “Reformation Day” potluck.

I guess Orthodox might also confuse Halloween with the Reformation…

The Abolition of Man and The Magician's Twin

When I first read The Abolition of Man as a student at Calvin College, I was quite enthralled, and in my political science class, I asked, “Do you agree with C.S. Lewis in The Abolition of Man ab—” and my teacher, a well-respected professor and a consummate communicator, cut me off before I could begin to say which specific point I was inquiring about, and basically said, “Yes and amen to the whole thing!” as as brilliant analysis of what is going on in both modernist and postmodernist projects alike.

C.S. Lewis's The Abolition of Man (available online in a really ugly webpage) is a small and easily enough overlooked book. It is, like Mere Christianity, a book in which a few essays are brought together in succession. In front matter, Lewis says that the (short) nonfiction title of The Abolition of Man and the (long) novel of That Hideous Strength represent two attempts to make the same basic point in two different literary formats. It isn't as flashy as The Chronicles of Narnia, and perhaps the first two essays are not captivating at the same level of the third. However, let me say without further argument here that the book is profoundly significant.

Let me bring in another partner in the dialogue: The Magician's Twin: C.S. Lewis, Science, Scientism, and Society. The title may need some explanation to someone who does not know Lewis, but I cannot ever read a book with so big a thesis so brilliantly summarized in so few words. There are allusions to two of his works: The Abolition of Man, which as discussed below calls the early scientist and the contemporary “high noon of magic” to be twins, motivated by science, but science blossomed and magic failed because science worked and magic didn't. (In other words, a metaphorical Darwinian “survival of the fittest” cause science to ultimately succeed and magic to ultimately fail). In The Magician's Nephew, Lewis has managed to pull off the rather shocking feat of presenting and critiquing the ultimately banal figures of the Renaissance magus and the Nietzchian Übermensch (and its multitude of other incarnations) in a way that is genuinely appropriate in a children's book. The title of “The Magician's Twin,” in three words including the word “The”, quotes by implication two major critiques Lewis provided, and one could almost say that the rest, as some mathematicians would say, “is left as an exercise for the reader.”

The book has flaws, some of them noteworthy, in particular letting Discovery Institute opinions about what Lewis would say trump what in fact he clearly did say. I detected, if I recall correctly, collisions with bits of Mere Christianity. And the most driving motivation is to compellingly argue Intelligent Design. However, I'm not interested in engaging origins questions now (you can read my muddled ebook on the topic here).

What does interest me is what The Magician's Twin pulls from The Abolition of Man's side of the family. On that point I quote Lewis's last essay at length:

Nothing I can say will prevent some people from describing this lecture as an attack on science. I deny the charge, of course: and real Natural Philosophers (there are some now alive) will perceive that in defending value I defend inter alia the value of knowledge, which must die like every other when its roots in the Tao [the basic wisdom of mankind, for which Lewis mentions other equally acceptable names such as “first principles” or “first platitudes”] are cut. But I can go further than that. I even suggest that from Science herself the cure might come.

I have described as a ‘magician's bargain' that process whereby man surrenders object after object, and finally himself, to Nature in return for power. And I meant what I said. The fact that the scientist has succeeded where the magician failed has put such a wide contrast between them in popular thought that the real story of the birth of Science is misunderstood. You will even find people who write about the sixteenth century as if Magic were a medieval survival and Science the new thing that came in to sweep it away. Those who have studied the period know better. There was very little magic in the Middle Ages: the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries are the high noon of magic. The serious magical endeavour and the serious scientific endeavour are twins: one was sickly and died, the other strong and throve. But they were twins. They were born of the same impulse. I allow that some (certainly not all) of the early scientists were actuated by a pure love of knowledge. But if we consider the temper of that age as a whole we can discern the impulse of which I speak.

There is something which unites magic and applied science while separating both from the wisdom of earlier ages. For the wise men of old the cardinal problem had been how to conform the soul to reality, and the solution had been knowledge, self-discipline, and virtue. For magic and applied science alike the problem is how to subdue reality to the wishes of men: the solution is a technique; and both, in the practice of this technique, are ready to do things hitherto regarded as disgusting and impious — such as digging up and mutilating the dead.

If we compare the chief trumpeter of the new era (Bacon) with Marlowe's Faustus, the similarity is striking. You will read in some critics that Faustus has a thirst for knowledge. In reality, he hardly mentions it. It is not truth he wants from the devils, but gold and guns and girls. ‘All things that move between the quiet poles ‘shall be at his command' and ‘a sound magician is a mighty god'. In the same spirit Bacon condemns those who value knowledge as an end in itself: this, for him, is to ‘use as a mistress for pleasure what ought to be a spouse for fruit.' The true object is to extend Man's power to the performance of all things possible. He rejects magic because it does not work; but his goal is that of the magician. In Paracelsus the characters of magician and scientist are combined. No doubt those who really founded modern science were usually those whose love of truth exceeded their love of power; in every mixed movement the efficacy comes from the good elements not from the bad. But the presence of the bad elements is not irrelevant to the direction the efficacy takes. It might be going too far to say that the modern scientific movement was tainted from its birth: but I think it would be true to say that it was born in an unhealthy neighbourhood and at an inauspicious hour. Its triumphs may have-been too rapid and purchased at too high a price: reconsideration, and something like repentance, may be required.

Is it, then, possible to imagine a new Natural Philosophy, continually conscious that the natural object' produced by analysis and abstraction is not reality but only a view, and always correcting the abstraction? I hardly know what I am asking for. I hear rumours that Goethe's approach to nature deserves fuller consideration — that even Dr Steiner may have seen something that orthodox researchers have missed. The regenerate science which I have in mind would not do even to minerals and vegetables what modern science threatens to do to man himself. When it explained it would not explain away. When it spoke of the parts it would remember the whole. While studying the It it would not lose what Martin Buber calls the Thou-situation. The analogy between the Tao of Man and the instincts of an animal species would mean for it new light cast on the unknown thing. Instinct, by the only known reality of conscience and not a reduction of conscience to the category of Instinct. Its followers would not be free with the words only and merely. In a word, it would conquer Nature without being at the same time conquered by her and buy knowledge at a lower cost than that of life.

Perhaps I am asking impossibilities.

I'm drawing a blank for anything I've seen in a life's acquaintance with the sciences to see how I have ever met this postulate as true.

In my lifetime I have seen a shift in the most prestigious of sciences, physics (only a mathematician would be insulted to be compared with a physicist), shift from an empirical science to a fashionable superstring theory in which physics abdicates from the ancient scientific discipline of refining hypotheses, theories, and laws in light of experiments meant to test them in a feedback loop. With it, the discipline of physics abdicates from all fully justified claim to be science. And this is specifically physics we are talking about: hence the boilerplate Physics Envy Declaration, where practitioners of one's own academic discipline are declared to be scientists-and-they-are-just-as-much-scientists-as-people-in-the-so-called-“hard-sciences”-like-physics.

I do not say that a solution could not come from science; I do say that I understand what are called the STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) disciplines after people started grinding a certain very heavy political axe, I've had some pretty impressive achievements, and C.S. Lewis simply did not understand the science of his time too far above the level of an educated non-scientist: probably the biggest two clues that give away The Dark Tower as the work of another hand are that the author ineptly portrays portraiture gone mad in a world where portraiture would never have come to exist, and that the manuscript is hard science fiction at a level far beyond even Lewis's science fiction. Lewis may have written the first science fiction title in which aliens are honorable, noble beings instead of vicious monsters, but The Dark Tower was written by someone who knew the hard sciences and hard science fiction much more than Lewis and humanities and literature much less. (The runner-up clue is anachronous placement of Ransom that I cannot reconcile with the chronological development of that character at any point in the Space Trilogy.)

However, that is just a distraction.

A third shoe to drop

There are three shoes to drop; one prominent archetype of modern science's first centuries has been hidden.

Besides the figure of the Renaisssance Magus and the Founding Scientist is the intertwined figure of the Reformer.

Now I would like to mention three reasons why Lewis might have most likely thought of it and not discussed it.

First of all, people who write an academic or scholarly book usually try to hold on to a tightly focused thesis. A scholar does not ordinarily have the faintest wish to write a 1000-volume encyclopedia about everything. This may represent a shift in academic humanism since the Renaissance and Early Modern times, but Lewis has written a small, focused, and readable book. I don't see how to charitably criticize Lewis on the grounds that he didn't write up a brainstorm of every possible tangent; he has written a short book that was probably aiming to tax the reader's attention as little as he could. Authors like Lewis might agree with a maxim that software developers quote: “The design is complete, not when there is nothing more to add, but when there is nothing more to take away.”

Second of all, it would cut against the grain of the Tao as discussed (the reader who so prefers is welcomed to use alternate phrasing like “first platitudes”). His appendix of quotations illustrating the Tao is relatively long and quotes Ancient Egyptian, Old Norse, Babylonian, Ancient Jewish, Hindu, Ancient Chinese, Roman, English, Ancient Christian, Native American, Greek, Australian Aborigines, and Anglo-Saxon, and this is integrated with the entire thrust of the book. If I were to attempt such a work as Lewis did, it would not be a particularly obvious time to try to make a sharp critique specifically about one tradition.

Thirdly and perhaps most importantly, C.S. Lewis is a founder of ecumenism as we know it today, and with pacifism / just war as one exception that comes to mind, he tried both to preach and to remain within “mere Christianity”, and it is not especially of interest to me that he was Protestant (and seemed to lean more Romeward to the end of his life). C.S. Lewis was one of the architects of ecumenism as we know it (ecumenism being anathematized heresy to the Orthodox Church as of 1987), but his own personal practice was stricter than stating one's opinions as opinions and just not sledgehammering anyone who disagrees. There is a gaping hole for the Mother of God and Ever-Virgin Mary in the Chronicles of Narnia; Aslan appears from the Emperor Beyond the Sea, but without any hint of relation to any mother that I can discern. This gaping hole may be well enough covered so that Christian readers don't notice, but once it's pointed out it's a bit painful to think about.

For the first and second reasons, there would be reason enough not to criticize Reformers in that specific book. However, this is the reason I believe C.S. Lewis did not address the third triplet of the Renaissance Magus, the Founder of Science, and the Reformer. Lewis's words here apply in full force to the Reformer: “It might be going too far to say that the modern scientific movement was tainted from its birth: but I think it would be true to say that it was born in an unhealthy neighbourhood and at an inauspicious hour.”

You have to really dig into some of the history to realize how intertwined the Reformation was with the occult. Lewis says, for one among many examples, “In Paracelsus the characters of magician and scientist are combined.” Some have said that what is now called Lutheranism should be called Melancthonism, because as has happened many times in history, a charismatic teacher with striking influence opens a door, and then an important follower works certain things out and systematizes the collection. In Melancthon the characters of Reformer, Scientist, and Astrologer are combined. Now I would like to address one distraction: some people, including Lewis (The Discarded Image), draw a sharp distinction between astrology in the middle ages and the emptied-out version we have today. He says that our lumping astrology in with the occult would have surprised practitioners of either: Renaissance magic tasserted human power while astrology asserted human impotence. The Magician's Twin interestingly suggests that astrology as discussed by C.S. Lewis is not a remnant of magic but as a precursor to present-day deterministic science. And there is an important distinction for those who know about astrology in relation to Melancthon. Medieval astrology was a comprehensive theory, including cosmology and psychology, where “judicial astrology”, meaning to use astrology for fortune-telling, was relatively minor. But astrology for fortune-telling was far more important to Melanchthon. And if there was quite a lot of fortune-telling on Melanchthon's resume, there was much more clamor for what was then called natural philosophy and became what we now know as >e,?science.

Another troubling weed in the water has to do with Reformation history, not specifically because it is an issue with the Reformation, but because of a trap historians fall into. Alisdair McGrath's Reformation Theology: An Introduction treats how many features common in Protestantism today came to arise, but this kind of thing is a failure in historical scholarship. There were many features present in Reformation phenomena that one rarely encounters in Protestant histories of the Reformation. Luther is studied, but I have not read in any Protestant source his satisfied quotation about going to a bar, drinking beer, and leering at the barmaids. I have not seen anything like the climax of Degenerate Moderns: Modernity as Rationalized Sexual Misbehavior, which covers Martin Luther's rejection of his vow of celibacy being followed by large-scale assault on others' celibacy (“liberating” innumerable nuns from their monastic communities), Luther's extended womanizing, and his marriage to a nun as a way to cut back on his womanizing. For that matter, I grew up in the Anabaptist tradition, from which the conservatism of the Amish also came, and heard of historic root in terms of the compilation of martyrdoms in Martyr's Mirror, without knowing a whisper of the degree to which Anabaptism was the anarchist wing of the Reformation.

Questions like “Where did Luther's Sola Scriptura come from?”, or “Where did the Calvinist tradition's acronym TULIP for ‘Total Depravity', ‘Unconditional Election', ‘Limited Atonement', ‘Irresistable Grace', and the ‘Perseverance of the Saints?' come from?” are legitimate historical questions. However, questions like these only ask about matters that have rightly or wrongly survived the winnowing of history, and they tend to favor a twin that survived and flourished over a twin that withered and died. This means that the chaos associated with the founders of Anabaptism do not linger with how truly chaotic the community was at first, and in general Protestant accounts of the Reformation fail to report the degree to which the Reformation project was connected to a Renaissance that was profoundly occultic.

A big picture view from before I knew certain things

In AI as an Arena for Magical Thinking among Skeptics, one of the first real works I wrote as an Orthodox Christian, I try to better orient the reader to the basic terrain:

We miss how the occult turn taken by some of Western culture in the Renaissance and early modern period established lines of development that remain foundational to science today. Many chasms exist between the mediaeval perspective and our own, and there is good reason to place the decisive break between the mediaeval way of life and the Renaissance/early modern occult development, not placing mediaeval times and magic together with an exceptionalism for our science. I suggest that our main differences with the occult project are disagreements as to means, not ends—and that distinguishes the post-mediaeval West from the mediaevals. If so, there is a kinship between the occult project and our own time: we provide a variant answer to the same question as the Renaissance magus, whilst patristic and mediaeval Christians were exploring another question altogether. The occult vision has fragmented, with its dominion over the natural world becoming scientific technology, its vision for a better world becoming political ideology, and its spiritual practices becoming a private fantasy.

One way to look at historical data in a way that shows the kind of sensitivity I'm interested in, is explored by Mary Midgley in Science as Salvation (1992); she doesn't dwell on the occult as such, but she perceptively argues that science is far more continuous with religion than its self-understanding would suggest. Her approach pays a certain kind of attention to things which science leads us to ignore. She looks at ways science is doing far more than falsifying hypotheses, and in so doing observes some things which are important. I hope to develop a similar argument in a different direction, arguing that science is far more continuous with the occult than its self-understanding would suggest. This thesis is intended neither to be a correction nor a refinement of her position, but development of a parallel line of enquiry.

It is as if a great island, called Magic, began to drift away from the cultural mainland. It had plans for what the mainland should be converted into, but had no wish to be associated with the mainland. As time passed, the island fragmented into smaller islands, and on all of these new islands the features hardened and became more sharply defined. One of the islands is named Ideology. The one we are interested in is Science, which is not interchangeable with the original Magic, but is even less independent: in some ways Science differs from Magic by being more like Magic than Magic itself. Science is further from the mainland than Magic was, even if its influence on the mainland is if anything greater than what Magic once held. I am interested in a scientific endeavour, and in particular a basic relationship behind scientific enquiry, which are to a substantial degree continuous with a magical endeavour and a basic relationship behind magic. These are foundationally important, and even if it is not yet clear what they may mean, I will try to substantiate these as the thesis develops. I propose the idea of Magic breaking off from a societal mainland, and sharpening and hardening into Science, as more helpful than the idea of science and magic as opposites.

There is in fact historical precedent for such a phenomenon. I suggest that a parallel with Eucharistic doctrine might illuminate the interrelationship between Orthodoxy, Renaissance and early modern magic, and science (including artificial intelligence). When Aquinas made the Christian-Aristotelian synthesis, he changed the doctrine of the Eucharist. The Eucharist had previously been understood on Orthodox terms that used a Platonic conception of bread and wine participating in the body and blood of Christ, so that bread remained bread whilst becoming the body of Christ. One substance had two natures. Aristotelian philosophy had little room for one substance which had two natures, so one thing cannot simultaneously be bread and the body of Christ. When Aquinas subsumed real presence doctrine under an Aristotelian framework, he managed a delicate balancing act, in which bread ceased to be bread when it became the body of Christ, and it was a miracle that the accidents of bread held together after the substance had changed. I suggest that when Zwingli expunged real presence doctrine completely, he was not abolishing the Aristotelian impulse, but carrying it to its proper end. In like fashion, the scientific movement is not a repudiation of the magical impulse, but a development of it according to its own inner logic. It expunges the supernatural as Zwingli expunged the real presence, because that is where one gravitates once the journey has begun. What Aquinas and the Renaissance magus had was composed of things that did not fit together. As I will explore below under the heading ‘Renaissance and Early Modern Magic,' the Renaissance magus ceased relating to society as to one's mother and began treating it as raw material; this foundational change to a depersonalised relationship would later secularise the occult and transform it into science. The parallel between medieval Christianity/magic/science and Orthodoxy/Aquinas/Zwingli seems to be fertile: real presence doctrine can be placed under an Aristotelian framework, and a sense of the supernatural can be held by someone who is stepping out of a personal kind of relationship, but in both cases it doesn't sit well, and after two or so centuries people finished the job by subtracting the supernatural.

What does the towering figure of the Reformer owe to the towering figure of the Renaissance Magus?

However little the connection may be underscored today, mere historical closeness would place a heavy burden of proof on the scholar who would deny that the Reformation owes an incalculable debt to the Renaissance that it succeeded. Protestant figures like Francis Schaeffer may be sharply critical of the Renaissance, but I've never seen them explain what the Reformation directly inherited.

The concept Sola Scriptura (that the Bible alone is God's supreme revelation and no tradition outside the Bible is authoritative) is poured out from the heart of the Reformation cry, “Ad fontes!” (that we should go to classical sources alone and straighten out things from there). The term “Renaissance” / “Renascence” means, by mediation of two different languages, “Rebirth”, and more specifically a rebirth going back to original classic sources and building on them directly rather than by mediation of centuries. Luther owes a debt here even if he pushed past the Latin Bible to the Greek New Testament, and again past the revelation in the Septuagint or Greek Old Testament (the patristic Old Testament of choice) to the original Hebrew, dropping quite a few books of the Old Testament in the process. (He contemplated deeper cuts than that, and called the New Testament epistle of James a “letter of straw,” fit to be burned.)

The collection of texts Luther settled on is markedly different to the Renaissance interest in most or all of the real gems of classical antiquity. However, the approach is largely inherited. And the resemblance goes further.

I wrote above of the Renaissance Magus, one heir of which is the creation of political ideology as such, who stands against the mainland but, in something approaching Messianic fantasy, has designs to tear apart and rebuild the despicable raw material of society into something truly worthwhile and excellent by the power of his great mind. On this point, I can barely distinguish the Reformer from the Renaissance Magus beyond the fact that the Reformer's raw material of abysmal society was more specifically the Church.

Exotic Golden Ages and Restoring Harmony with Nature: Anatomy of a Passion was something I wrote because of several reasons but triggered, at least, by a museum visit which was presented as an Enlightenment exhibit, and which showed a great many ancient, classical artifacts. After some point I realized that the exhibit as a whole was an exhibit on the Enlightenment specifically in the currents that spawned the still-living tradition of museums, and the neo-classicism which is also associated that century. I don't remember what exact examples I settled on, and the article was one where examples could be swapped in or out. Possible examples include the Renaissance, the Reformation, Enlightenment neo-classicism, various shades of postmodernism, neo-paganism, the unending Protestant cottage industry of reconstructing the ancient Church, unending works on trying to make political ideologies that will transform one's society to be more perfect, and (mumble) others; I wrote sharply, “Orthodoxy is pagan. Neo-paganism isn't,” in The Sign of the Grail, my point being that if you want the grandeur of much of any original paganism (and paganism can have grandeur), you will do well to simply skip past the distraction and the mad free-for-all covered in even pro-paganism books like Drawing Down the Moon, and join the Orthodox Church, submitting to its discipline.

The Renaissance, the founding of modern science, and the Reformation have mushy, porous borders. This isn't how we conceptualize things today, but then you could have pretty much been involved one, or any two, or all three.

The Renaissance Magus, the Founder of Science, and the Reformer are triplets!

Halloween: The Second U.S. National Holiday: Least Successful Christianization Ever!

There has been some background noise about Christianity incorporating various pagan customs and transforming them, often spoken so that the original and merely pagan aspect of the custom appears much more enticing than anything else. My suspicion is that this has happened many times, although most of the such connections I've heard, even from an Orthodox priest, amount to urban legend.

For example, one encyclopedia or reference material that I read when I was in gradeschool talked about how, in the late Roman Empire, people would celebrate on December 21st or 22nd, and remarked briefly that Christians could be identified by the fact that they didn't bear swords. The Roman celebration was an annual celebration, held on the solstice, and Christians didn't exactly observe the pagan holiday but timed their own celebration of the Nativity of Christ so as to be celebrated. And along the centuries, with the frequent corruptions that occurred with ancient timekeeping, the Nativity got moved just a few days to the 25th. However, ever recent vaguely scholarly treatment I have read have said that the original date of the Nativity was determined by independent factors. There was a religious belief stating that prophets die on an anniversary of their conception or birth, and the determination that placed the Nativity on December 25th was a spillover calculation to a date deemed more central, the Annunciation as the date when Christ was conceived, set as March 25th.

I do not say that all claims of Christianization of pagan custom are bogus; probably innumerable details of Orthodoxy are some way or other connected with paganism. However, such claims appearing in the usual rumor format, much like rumor science, rarely check out.

However, Halloween is a bit of anomaly.

Of all the attempts to Christianize a pagan custom, Halloween is the most abject failure. In one sense the practice of Christmas, with or without a date derived from a pagan festival, does not seem harmed by it. The Christmas tree may or may not be in continuity with pre-Christian pagan customs; but in either case the affirmative or negative answer does not matter that much. It was also more specifically a custom that came from the heterodox West, and while Orthodox Christians might object to that or at least not see the need, I am not interested in lodging a complaint against the custom. Numerous first-world Christians have complained about a commercialization of Christmas that does in fact does matter and poisons the Christmas celebration: C.S. Lewis, one might mention here, sounds off with quite a bit of success. My own college-day comment in Hayward's Unabridged Dictionary went:

Christmas, n. A yearly holiday celebrating the coming of the chief Deity of Western civilization: Mammon.

And commercial poisoning of the Christmas spirit was also core to my The Grinch Who Stole Christmas. One might join many others and speak, instead of a Christianization of a pagan custom, of the commercialization of a Christian custom.

However, Halloween, or various archaic spellings and names that are commonly dug up, has kept its original character after a thousand years or so, and the biggest real dent in its character is that you don't need to dress up as something dead or occult (or both); the practice exists of dressing up for Halloween as something that is not gruesome. Celebrities and characters from treasured TV shows and movies are pretty much mainstream costumes. But it is a minority, and the Christmas-level escalating displays in people's front yards are, at least in my neck of the woods, all gruesome.

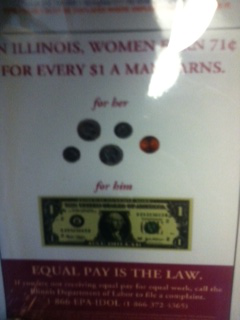

Martin Luther is in fact believed by many to have published his 95 theses (or at least made another significant move) on October 31, 1517, and people have been digging it up perhaps more than ever, this year marking a 500th anniversary. I only heard of “Reformation Day” for the first time as a junior in college, and the wonderful professor mentioned above asked me, “What do you think of celebrating Reformation Day?” and probably expecting something pungent. I answered, “I think celebrating one ghastly event per day is enough!”

Christianization attempts notwithstanding, Halloween seems to be growing and growing by the year!

Alchemy no longer needs to come out of the closet

Today the occult is in ascendancy and alchemy is coming out of the closet, or rather has been out of the closet from some time and still continuing to move away from it. Now there have been occult-heavy times before; besides the three triplets of Renaissance Magus, Founder of Science, and Reformer several centuries back, the Victorian era was at once the era of Romanticism and Logical Positivism, and at once an era with very strictly observe modesty and of a spiritualism that posited a spiritual realm of “Summer-land” where gauzy clothing could quickly be whisked away. Alchemy is now said to be more or less what modern science arose out of, and people are no longer surprised to hear that Newton's founding of the first real physics that is part of the physics curriculum was given a small fraction of the time he devoted to pursuing alchemy. I haven't yet gotten all the way through Owen Barfield's Saving the Appearances: A History of Idolatry as it reads to me as choking antithesis to an Orthodox theology that is pregnant with icon. However, one of the steps along the way I did read was one talking about the heart, and, characteristic of many things in vogue today, he presents one figure as first introducing a mechanistic understanding of the heart as a pump that drives blood through the system of vessels: that much is retained at far greater detail in modern science, but in that liminal figure, such as alchemists love, the heart was still doing major alchemical jobs even if his successors may have abandoned them.

Today there are some people who have made some sharp apologetic responses. Books endorsed on Oprah may treat alchemy as supreme personal elevation. However, conservative authors acknowlege some points while condemning others as barren. It is perhaps true that alchemy represents a tradition intended to transform the practitioner spiritually. But alchemy is false in that spiritual transformation is approached through master of technique and “sympathetic magic” as Bible scholars use the term. We do not need a technique to transform us spiritually. We may need repentance, faith, spiritual discipline that is neither more nor less than a cooperation with God, and communion, and in the Holy Mysteries we have a transformation that leaves gold in the dust. And alchemy is in the end positively anemic when it stands next to full-blooded religion. And really, what person in any right mind would crawl on broken glass to create gold when Someone will give you the Providence of the true Dance and make the divine Life pulse through your blood?

A while ago, I wrote a poem, How Shall I Tell an Alchemist? which is I think where I'll choose to end this section:

How Shall I Tell an Alchemist?

The cold matter of science—

Exists not, O God, O Life,

For Thou who art Life,

How could Thy humblest creature,

Be without life,

Fail to be in some wise,

The image of Life?

Minerals themselves,

Lead and silver and gold,

The vast emptiness of space and vacuum,

Teems more with Thy Life,

Than science will see in man,

Than hard and soft science,

Will to see in man.How shall I praise Thee,

For making man a microcosm,

A human being the summary,

Of creation, spiritual and material,

Created to be,

A waterfall of divine grace,

Flowing to all things spiritual and material,

A waterfall of divine life,

Deity flowing out to man,

And out through man,

To all that exists,

And even nothingness itself?And if I speak,

To an alchemist who seeks true gold,

May his eyes be opened,

To body made a spirit,

And spirit made a body,

The gold on the face of an icon,

Pure beyond twenty-four carats,

Even if the icon be cheap,

A cheap icon of paper faded?How shall I speak to an alchemist,

Whose eyes overlook a transformation,

Next to which the transmutation,

Of lead to gold,

Is dust and ashes?

How shall I speak to an alchemist,

Of the holy consecration,

Whereby humble bread and wine,

Illumine as divine body and blood,

Brighter than gold, the metal of light,

The holy mystery the fulcrum,

Not stopping in chalice gilt,

But transforming men,

To be the mystical body,

The holy mystery the fulcrum of lives transmuted,

Of a waterfall spilling out,

The consecration of holy gifts,

That men may be radiant,

That men may be illumined,

That men be made the mystical body,

Course with divine Life,

Tasting the Fountain of Immortality,

The transformed elements the fulcrum,

Of God taking a lever and a place to stand,

To move the earth,

To move the cosmos whole,

Everything created,

Spiritual and material,

Returned to God,

Deified.And how shall I tell an alchemist,

That alchemy suffices not,

For true transmutation of souls,

To put away searches for gold in crevices and in secret,

And see piles out in the open,

In common faith that seems mundane,

And out of the red earth that is humility,

To know the Philosopher's Stone Who is Christ,

And the true alchemy,

Is found in the Holy Orthodox Church?How Shall I Tell an Alchemist?

Most of us are quite clueless, and we are just as much clueless as people in the so-called “hard science” like physics!

If one begins to study not exactly physics itself, but the people who best contributed to 20th century physics, the first and most popular name will likely be Albert Einstein. However, if one extends the list of names, Nobel Prize laureate Richard P. Feynman will come up pretty quickly. He provided a series of lectures now known as the Feynman lectures, which are widely held as some of the most exemplary communication in the sciences around. He also gave a graduation lecture called “Cargo Cult Science” in which he demonstrates a lack of understanding of history. Its opening sentences read,

During the Middle Ages there were all kinds of crazy ideas, such as that a piece of rhinoceros horn would increase potency. (Another crazy idea of the Middle Ages is these hats we have on today—which is too loose in my case.) Then a method was discovered for separating the ideas—which was to try one to see if it worked, and if it didn't work, to eliminate it. This method became organized, of course, into science. And it developed very well, so that we are now in the scientific age.

Sorry. No. This gets an F. Parts are technically true, but this gets an F. It is not clear to me that it even reaches the dignity of cargo cult history. (On Feynman's account, cargo cults usually managed to make something look like real airports.) If you don't understand history, but leap centuries in a single bound, don't presume to summarize the whole of it in a short paragraph. Feynman's attempt to summarize as much of the sciences as possible in a single sentence is impressively well-done. This is not.

I wish to make use of Darwin, and what I will call “Paleo-Darwinism”, which I would distinguish from any version of Darwinism and evolution which is live in the academy.

What is called “Darwinism” or “evolution” has changed markedly from anything I can meaningfully connect with the theory Darwin articulated in The Origin of Species.

Some of the terms remain the same, and a few terms like “natural selection” even keep their maiden names. However, Darwin's theory was genuinely a theory of evolution, meaning that life forms slowly evolve, and we should expect a fossil record that shows numerous steps of gradual transitions. There are multiple live variations of evolution in biology departments in mainstream academics, and I don't know all the variations. However, my understanding is that part of the common ground between competing variations is that the fossil record is taken at face value and while there is common ancestry of a form, all the evidence we have is that there long periods of extreme stability with surprisingly little change worthy of the name, which are suddenly and miraculously interrupted by the appearance of new forms of life without preserved record of intermediate forms.

For this discussion I will be closer to Darwin's theory in the original, and I wish to explicitly note that I am not intending, or pretending, to represent any theory or concept that is live in the biological sciences. By “Evolution” I mean Paleo-Evolution, an ongoing acquirement of gradual changes. And I would furthermore want to note the distinction between natural selection, and artificial selection.

Artificial selection, meaning breeding, was presumably a readily available concept to the 19th century mind. It was, or at least should be, a readily available concept thousands of years older than the dawn of modern science. Farmers had controlled mating within a gene pool to increase certain traits and diminish others. To an economy that was at least a little closer to farming, breeding was the sort of concept well enough available that someone might use it as a basis for an analogy or metaphor.

It appears that Darwin did just that. He introduced a concept of natural selection, something that might seem odd at first but was intelligible. “Natural selection” meant that there was something like breeding going on even in the absence of a breeder. Instead of farmers breeding (I think the term ecosystem may be anachronism to place in Darwin's day and it apparently does not appear in his writing, but the term fits in Paleo-Darwinism as well as in newer forms like a glove), natural selection is a mechanism by which the natural environment will let organisms that survive continue to propagate, and organisms that can't survive won't propagate either. There is a marked difference between animals that are prey animals and those that aren't. Animals that contend with predators tend to have sharp senses to notice predators, the ability to flee predators, and the ability to put up a fight. None of these traits is absolutely essential, but mice that do not evade cats cease to exist. Dodos in Darwin's day, or field chickens in the 19th century U.S., did not face predators and at least the dodos were quickly hunted to extinction when humans discovered the place.

I wish to keep this distinction between two different methods and selections in saying that artificial selection is not the only selection and the scientific method is not the only selection either.

What else is there? Before a Paleo diet stopped some really nasty symptoms, I read Nourishing Traditions. That book documents, in scientific terms, ways and patterns of eating that are beneficial, even though those dishes appeared well before we had enough scientific understanding to dissect the benefits. Buttered asparagus, for instance, provides a nutritionally beneficial that is greater than the nutritional value of its parts. And there are many things; the author, celebrating fermentation, says that if you have a Ruben, you are eating five fermented foods.

The point I would make about (here) diet is that independently of scientific method, societies that had choices about what to eat tended by something like natural selection to optimize foods within their leeway that were beneficial.

Science has a very valuable way to select theories and laws that is really impressive. However, it is not the only winnowing fork available, and the other winnowing fork, analogous to natural selection, is live and powerful. And, though this is not really a fair comparison, a diet that has been passed down for generations in a society is almost certainly better than the industrial diet that is causing damage to people worldwide who can't afford their traditional cuisine.

There exist some foods which were scientifically engineered to benefit the eater. During World War II, experiments were run on volunteers to know what kind of foods would bring the best benefits and best chance of survival to liberated, starving concentration camp prisoners. Right now even my local government has gotten a clue that breast milk is vastly better for babies than artificial formula, but people have still engineered a pretty impressive consolation prize in baby formulas meant to be as nourishing as possible (even if they still can't confer the immune benefits conferred by mother's milk). However, 99% of engineered foods are primarily intended to make a commercially profitable product. Concern for the actual health of the person eating the food is an afterthought (if even that).

Withered like Merlin—and, in a mirror, withered like me!

I would like to quote That Hideous Strength, which again was an attempt at a novel that in fictional format would explore the same terrain explored in the three essays of the nonfiction The Abolition of Man; it is among the book's most haunting passages to me.

“…But about Merlin. What it comes to, as far as I can make out, is this. There were still possibilities for a man of that age which there aren't for a man of ours. The earth itself was more like an animal in those days. And mental processes were much more like physical actions. And there were—well, Neutrals, knocking about.”

“Neutrals?”

“I don't mean, of course, that anything can be a real neutral. A conscious being is either obeying God or disobeying Him. But there might be things neutral in relation to us.”

“You mean eldils—angels?”

“Well, the word angel rather begs the question. Even the Oyéresu aren't exactly angels in the same sense as our guardian angels are. Technically they are Intelligences. The point is that while it may be true at the end of the world to describe every eldil either as an angel or a devil, and may even be true now, it was much less true in Merlin's time. There used to be things on this Earth pursuing their own business, so to speak. They weren't ministering spirits sent to help fallen humanity; but neither were they enemies preying upon us. Even in St. Paul one gets glimpses of a population that won't exactly fit into our two columns of angels and devils. And if you go back further . . . all the gods, elves, dwarves, water-people, fate, longaevi. You and I know too much to think they are illusions.”

“You think there are things like that?”

“I think there were. I think there was room for them then, but the universe has come more to a point. Not all rational beings perhaps. Some would be mere wills inherent in matter, hardly conscious. More like animals. Others—but I don't really know. At any rate, that is the sort of situation in which one got a man like Merlin.”

“It was rather horrible. I mean even in Merlin's time (he came at the extreme tail end of it) though you could still use that sort of life in the universe innocently, you couldn't do it safely. The things weren't bad in themselves, but they were already bad for us. They sort of withered the man who dealt with them. Not on purpose. They couldn't help doing it. Merlinus is withered. He's quite pious and humble and all that, but something has been taken out of him. That quietness of his is just a little deadly, like the quiet of a gutted building. It's the result of having his mind open to something that broadens the environment just a bit too much. Like polygamy. It wasn't wrong for Abraham, but one can't help feeling that even he lost something by it.”

“Cecil,” said Mrs. Dimble. “Do you feel quite comfortable about the Director's using a man like this? I mean, doesn't it look a bit like fighting Belbury with its own weapons?”

“No. I had thought of that. Merlin is the reverse of Belbury. He's at the opposite extreme. He is the last vestige of an old order in which matter and spirit were, from our modern point of view, confused. For him every operation on Nature is a kind of personal contact, like coaxing a child or stroking one's horse. After him came the modern man to whom Nature is something to be dead—a machine to be worked, and taken to bits if it won't work the way he pleases. Finally, come the Belbury people who take over that view from the modern man unaltered and simply want to increase their powers by tacking on the aid of spirits—extra-natural, anti-natural spirits. Of course they hoped to have it both ways. They thought the old magia of Merlin which worked with the spiritual qualities of Nature, loving and reverencing them and knowing them from within, could be combined with the new goetia—the brutal surgery from without. No. In a sense Merlin represents what we've got to get back to in some different way. Do you know that he is forbidden by the rules of order to use any edged tool on any growing thing?”

I find this passage to speak a great truth, but coming the opposite direction! Let me explain.

I might briefly comment that the virtues that are posited to have pretty much died with Merlin are alive and kicking in Orthodoxy; see “Physics.” The Orthodox Christian is in a very real sense not just in communion with fellow Orthodox Christians alive on earth: to be in communion with the Orthodox Church is to be in communion with Christ, in communion with saints and angels, in communion with Creation from stars to starlings to stoplights, and even in a certain sense in communion with heterodox at a deeper level than the heterodox are in communion with themselves. This is present among devout laity, and it is given a sharper point in monasticism. It may be completely off-limits for a married or monastic Orthodox to set out to be like Merlin, but a monastic in particular who seeks first the Kingdom of God and his perfect righteousness may end up with quite a lot of what this passage sells Merlin on.

Now to the main part: I think the imagery in this passage brings certain truths into sharper contrast if it is rewired as a parable or allegory. I do not believe, nor do I ask you to believe, that there have ever been neutral spirits knocking about, going about on their own business. However, the overall structure and content work quite well with technologies: besides apocalyptic prophecies about submarines and radio being fulfilled in the twentieth century, there is something very deep about the suggestion that technology “sort of withers” the person dealing with it. I think I represent a bit of a rarity in that I have an iPhone, I use it, but I don't use it all that much when I don't need it. In particular I rarely use it to kill time, or when I know I should be doing something else. That's an exception! The overall spiritual description of Merlin's practices fits our reception of technology very well.

I have a number of titles on Amazon, and I would like to detail what I consider the most significant three things I might leave behind:

- The Best of Jonathan's Corner: This is my flagship title, and also the one I am most pleased with reception.

- “The Seraphinians: “Blessed Seraphim Rose” and His Axe-Wielding Western Converts: More than any other of my books this book is a critique, and part of its 1.4 star review on Amazon is because Fr. Seraphim's following seems to find the book extremely upsetting, and so the most helpful review states that the book is largely unintelligible, and casts doubt on how sober I was when I was writing it. I'm a bit more irritated that the title has received at least two five-star reviews that I am aware of, and those reviews universally vanish quickly. (I tried to ask Amazon to restore deleted reviews, but Amazon stated that their policy is that undeleting a censored review constitutes an unacceptable violation of the reviewer's privacy.)

- The Luddite's Guide to Technology: At the time of this writing, I have one review, and it is kind. However, I'm a bit disappointed in the book's relative lack of reception. I believe it says something significant, partly because it is not framed in terms of “religion and science”, but “technology and faith”. Right and ascetically-based use of technology would seem to be a very helpful topic, and if I may make a point about Merlin, he appears to have crossed the line where if he drove he could get a drunk driving conviction. We, on the other hand, are three sheets to the wind.

“They sort of withered the man who dealt with them:”

Mathematician and Renaissance Man

I ranked 7th in the nation in the 1989 MathCounts competition, and that is something to be very humble about. There's more than just jokes that have been floating around about, “How can you tell if a mathematician is an extravert?”—”He looks at your feet when he talks to you!”

In the troubled course of my troubled relationship with my ex-fiancée, I am not interested in disclosing my ex-fiancée's faults. I am, however, interested in disclosing my own faults in very general terms. The root cause in most cases came from acting out of an overly mathematical mind, very frequently approaching things as basically a math problem to solve and relating to her almost exclusively with my head rather than my heart, and really, in the end, not relating to her as properly human (and, by the same stroke, not relating to myself as properly human either).

I do not say that the relationship would have succeeded if I had avoided this fault and the blunders that came up downwind of it. I am also not interested in providing a complete picture. I mention this for one reason: to say that at a certain level, a very mathematical mind is not really good for us!

This is something that is true at a basic level; it is structural and is built into ourselves as persons. Some vices are in easier reach. The Orthodox understanding is that the nous or spiritual eye is the part of us that should guide us both; the dianoia or logic-related understanding has a legitimate place, but the relation between the nous and the dianoia should ideally be the relationship between the sun and the moon. One Orthodox figure characterized academic types as having a hypertrophied or excessive, out-of-check logic-handling dianoia, and a darkened nous. I plead guilty on both counts, at least in my mathematical formation.

I might also recall a brief point from Everyday Saints, a book that has managed to get a pretty long book hold waitlist at some libraries. A Soviet government agent commented, rather squeamishly, that highly educated prisoners were the first to crack under torture.

Prayerful manual labor is considered normative in Orthodox monasticism, and in a monastery, the novices who are asked to do extensive manual labor are being given a first choice offering. The fact that abbots do less labor than most other monks is not a privilege of authority. Rather, it is a deprivation. The reduced amount of manual labor is a concession to necessities, and many abbots would exchange their responsibilities with those of a novice in a heartbeat.

(I have been told, “Bishops wish they were novices!”)

Along more recent lines, I have been called a Renaissance man, or less often a genius. I felt a warm glow in being called a Renaissance man; I took the term as a minor social compliment recognizing broad-ranging interests and achievements, and not really much more than that, or much more important. Then I pulled up the Wikipedia article for “polymath,” read the section on Renaissance men, and my blood ran cold.

The article does not even pretend to list detail of what was expected of Renaissance men, but as I ran down the list of distinctions, I realized that I had pretty much every single achievement on the list, and education, and a good deal more. And what came to me was, “I'm coming down on the side of Barlaam and not St. Gregory Palamas!” (For non-Orthodox readers, Barlaam and St. Gregory were disputants in a controversy where Barlaam said that Orthodox monks chiefly needed lots of academic learning and what would today be called the liberal arts ideal, and St. Gregory said that monks chiefly need the unceasing prayer usually called “prayer of the heart.”)

There was one executive who said, “I climbed to the top of the corporate ladder only to find that it was leaning against the wrong building,” and that's pretty much where I found myself.

I have had less of a mathematical mind by the year, and I am hoping through monasticism to let go of things other than thoroughly seeking God, and let go of my Renaissance man chassis. My hope in monasticism is to try and follow the same path St. Gregory Palamas trod, and spend what time I have remaining in repentance (better late than never).

I now have a silence somewhat like the silence of a gutted building.

I seek the silence of hesychasm.

One wise priest said again and again, “The longest journey we will take is the journey from our mind to our heart.”

An Open Letter to Catholics on Orthodoxy and Ecumenism

What might be called "the Orthodox question"

I expect ecumenical outreach to Orthodox has been quite a trying experience for Catholics. It must seem to Catholics like they have made Orthodoxy their top ecumenical priority, and after they have done their best and bent over backwards, many Orthodox have shrugged and said, "That makes one of us!" or else made a nastier response. And I wonder if Catholics have felt a twinge of the Lord's frustration in saying, "All day long I have held out my hands to a rebellious and stubborn people." (Rom 10:21)

In my experience, most Catholic priests have been hospitable: warm to the point of being warmer to me than my own priests. It almost seems as if the recipe for handling Orthodox is to express a great deal of warmth and warmly express hope for Catholics and Orthodox to be united. And that, in a nutshell, is how Catholics seem to conceive what might be called "the Orthodox question."

And I'm afraid I have something painful to say. Catholics think Orthodox are basically the same, and that they understand us. And I'm asking you to take a tough pill to swallow: Catholics do not understand Orthodox. You think you do, but you don't.

I'd like to talk about an elephant in the room. This elephant, however painfully obvious to Orthodox, seems something Catholics are strikingly oblivious to.

A conciliatory gesture (or so I was told)

All the Orthodox I know were puzzled for instance, that the Pope thought it conciliatory to retain titles such as "Vicar of Jesus Christ," "Successor of the Prince of the Apostles," and "Supreme Pontiff of the Universal Church," but drop "Patriarch of the West." Orthodox complain that the Roman bishop "was given primacy but demanded supremacy," and the title "Supreme Pontiff of the Universal Church" is offensive. Every bishop is the successor of the prince of the apostles, so reserving that title to the Pope is out of line. But Orthodoxy in both ancient and modern times regards the Pope as the Patriarch of Rome, and the Orthodox Church, having His Holiness IGNATIUS the Patriarch of Antioch and all the East, has good reason to call the Patriarch of Rome, "the Patriarch of the West." The response I heard to His Holiness Benedict dropping that one title while retaining the others, ranged from "Huh?" to, "Hello? Do you understand us at all?"

What Catholics never acknowledge

That is not a point I wish to belabor; it is a relatively minor example next to how, when in my experience Catholics have warmly asked Orthodox to reunify, never once have I seen any recognition or manifest awareness of the foremost concern Orthodox have about Rome and Constantinople being united. Never once have I seen mere acknowledgment of the Orthodox concern about what Rome most needs to repent of.

Let me clarify that slightly. I've heard Catholics acknowledge that Catholics have committed atrocities against Orthodox in the past, and Catholics may express regrets over wrongs from ages past and chide Orthodox for a lack of love in not being reunified. But when I say, "what Rome most needs to repent of," I am not taking the historian's view. I'm not talking about sack of the Constantinople, although people more Orthodox than me may insist on things like that. I am not talking about what Rome has done in the past to repent of, but what is continuing now. I am talking about the present tense, and in the present tense. When Catholics come to me and honor Orthodoxy with deep warmth and respect and express a desire for reunion, what I have never once heard mention of is the recantation of Western heresy.

This may be another tough pill to swallow. Catholics may know that Orthodox consider Catholics to be heretics, but this never enters the discussion when Catholics are being warm and trying to welcome Orthodox into their embrace. It's never acknowledged or addressed. The warm embrace instead affirms that we have a common faith, a common theology, a common tradition: we are the same, or so Orthodox are told, in all essentials. If Orthodox have not restored communion, we are told that we do not recognize that we have all the doctrinal agreement properly needed for reunification.

But don't we agree on major things? Rome's bishops say we do!

I would like to outline three areas of difference and give some flesh to the Orthodox claim that there are unresolved differences. I would like to outline one issue about what is theology, and then move on to social ethics, and close on ecumenism itself. I will somewhat artificially limit myself to three; some people more Orthodox than me may wonder why, for instance, I don't discuss the filioque clause (answer: I am not yet Orthodox enough to appreciate the importance given by my spiritual betters, even if I do trust that they are my spiritual betters). But there's a lot in these three.

To Catholics who insist that we share a common faith, I wish to ask a question that may sound flippant or even abrasive. A common faith? Really? Are you ready to de-canonize Thomas Aquinas and repudiate his scholasticism? Because Orthodox faith is something incompatible with the "theology" of Thomas Aquinas, and if you don't understand this, you're missing something fundamental to Orthodox understandings of theology. And if you're wondering why I used quotes around "theology," let me explain. Or, perhaps better, let me give an example.

See the two texts below. One is chapter 5 in St. Dionysius (or, if you prefer, pseudo-Dionysius), The Mystical Theology. That gem is on the left. To the right is a partial rewriting of the ideas in the style of Thomas Aquinas's Summa Theologiæ.

| St. Dionysius the Areopagite, "The Mystical Theology" | Rewritten in the scholastic style of Thomas Aquinas |

|---|---|

|

Again, as we climb higher we say this. It is not soul or mind, nor does it possess imagination, conviction, speech, or understanding. Nor is it speech per se, understanding per se. It cannot be spoken of and it cannot be grasped by understanding. It is not number or order, greatness or smallness, equality or inequality, similarity or dissimilarity. It is not immovable, moving, or at rest. It has no power, it is not power, nor is it life. It is not a substance, nor is it eternity or time. It cannot be grasped by the understanding since it is neither knowledge nor truth. It is not kingship. It is not wisdom. It is neither one nor oneness, divinity nor goodness. Nor is it a spirit, in the sense that we understand the term. It is not sonship or fatherhood and it is nothing known to us or to any other being. It falls neither within the predicate of nonbeing nor of being. Existing beings do not know it as it actually is and it does not know them as they are. There is no speaking of it, nor name nor knowledge of it. Darkness and light, error and truth—it is none of these. It is beyond every assertion and denial. We make assertions and denials of what is next to it, but never of it, for it is both beyond every assertion, being the perfect and unique cause of all things, and, by virtue of its preeminently simple and absolute nature, it is also beyond every denial. |

Question Five: Whether God may accurately be described with words and concepts. Objection One: It appears that God may be accurately described, for otherwise he could not be described as existing. For we read, I AM WHO AM, and if God cannot be described as existing, then assuredly nothing else can. But we know that things exist, therefore God may be accurately described as existing. Objection Two: It would seem that God may be described with predicates, for Scripture calls him Father, Son, King, Wisdom, etc. Objection Three: It appears that either affirmations or negations must accurately describe God, for between an affirmation and its negation, exactly one of them must be true. On the Contrary, I reply that every affirmation and negation is finite, and in the end inadequate beyond measure, incapable of containing or of circumscribing God. We should remember that the ancients described God in imperfect terms rather than say nothing about him at all... |

Lost in translation?

There is something lost in "translation" here. What exactly is lost? Remember Robert Frost's words, "Nothing of poetry is lost in translation except for the poetry." There is a famous, ancient maxim in the Orthodox Church's treasured Philokalia saying, "A theologian is one who prays truly, and one who prays truly is a theologian:" theology is an invitation to prayer. And the original Mystical Theology as rendered on the left is exactly that: an invitation to prayer, while the rewrite in the style of the Summa Theologiæ has been castrated: it is only an invitation to analysis and an impressively deft solution to a logic puzzle. The ideas are all preserved: nothing of the theology is lost in translation except for the theology. And this is part of why Archimandrite Vasileos, steeped in the nourishing, prayerful theology of the Orthodox Church, bluntly writes in Hymn of Entry that scholastic theology is "an indigestible stone."

Thomas Aquinas drew on Greek Fathers and in particular St. John the Damascene. He gathered some of the richest theology of the East and turned it into something that is not theology to Orthodox: nothing of the Greek theology was lost in the scholastic translation but the theology! And there is more amiss in that Thomas Aquinas also drew on "the Philosopher," Aristotle, and all the materialistic seeds in Aristotelianism. (The Greeks never lost Aristotle, but they also never made such a big deal about him, and to be called an Aristotelian could be a strike against you.) There is a spooky hint of the "methodological agnosticism" of today's academic theology—the insistence that maybe you have religious beliefs, but you need to push them aside, at least for the moment, to write serious theology. The seed of secular academic "theology" is already present in how Thomas Aquinas transformed the Fathers.

This is a basic issue with far-reaching implications.

Am I seriously suggesting that Rome de-canonize Thomas Aquinas? Not exactly. I am trying to point out what level of repentance and recantation would be called for in order that full communion would be appropriate. I am not seriously asking that Rome de-canonize Thomas Aquinas. I am suggesting, though, that Rome begin to recognize that nastier and deeper cuts than this would be needed for full communion between Rome and Orthodoxy. And I know that it is not pleasant to think of rejoining the Orthodox Church as (shudder) a reconciled heretic. I know it's not pleasant. I am, by the grace of God, a reconciled heretic myself, and I recanted Western heresy myself. It's a humbling position, and if it's too big a step for you to take, it is something to at least recognize that it's a big step to take, and one that Rome has not yet taken.

The Saint and the Activist

Let me describe two very different images of what life is for. The one I will call "the saint" is that, quite simply, life is for the contemplation of God, and the means to contemplation is largely ascesis: the concrete practices of a life of faith. The other one, which I will call, "the activist," is living to change the world as a secular ideology would understand changing the world. In practice the "saint" and the "activist" may be the ends of a spectrum rather than a rigid dichotomy, but I wish at least to distinguish the two, and make some remarks about modern Catholic social teaching.

Modern Catholic social teaching could be enlightened. It could be well meant. It could be humane. It could be carefully thought out. It could be a recipe for a better society. It could be providential. It could be something we should learn from, or something we need. It could be any number of things, but what it absolutely is not is theology. It is absolutely not spiritually nourishing theology. If, to Orthodox, scholastic theology like that of Thomas Aquinas is as indigestible as a stone, modern Catholic social teaching takes indigestibility to a whole new level—like indigestible shards of broken glass.

The 2005 Deus Caritas Est names the Song of Songs three times, and that is without precedent in the Catholic social encyclicals from the 1891 Rerum Novarum on. Look for references to the Song of Songs in their footnotes—I don't think you'll find any, or at least I didn't. This is a symptom of a real problem, a lack of the kind of theology that would think of things like the Song of Songs—which is highly significant. The Song of Songs is a favorite in mystical theology, the prayerful theology that flows from faith, and mystical theology is not easily found in the social encyclicals. I am aware of the friction when secular academics assume that Catholic social teaching is one more political ideology to be changed at will. I give some benefit of the doubt to Catholics who insist that there are important differences, even if I'm skeptical over whether the differences are quite so big as they are made out to be. But without insisting that Catholic social teaching is just another activist ideology, I will say that it is anything but a pure "saint" model, and it mixes in the secular "activist" model to a degree that is utterly unlawful to Orthodox.

Arius is more scathingly condemned in Orthodox liturgy than even Judas. And, contrary to current fashion, I really do believe Arius and Arianism are as bad as the Fathers say. But Arius never dreamed either of reasoning out systematic theology or of establishing social justice. His Thalia are a (perhaps very bad) invitation to worship, not a systematic theology or a plan for social justice. In those regards, Catholic theology not only does not reach the standard of the old Orthodox giants: it does not even reach the standard of the old arch-heretics!

Catholics today celebrate Orthodoxy and almost everything they know about us save that we are not in full communion. Catholic priests encourage icons, or reading the Greek fathers, or the Jesus prayer: "Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me, a sinner." But what Catholics may not always be mindful of is that they celebrate Orthodoxy and put it alongside things that are utterly anathema to Orthodox: like heartily endorsing the Orthodox Divine Litugy and placing it alongside the Roman mass, Protestant services, Unitarian meetings, Hindu worship, and the spiritualist séance as all amply embraced by Rome's enfolding bosom.

What we today call "ecumenism" is at its root a Protestant phenomenon. It stems from how Protestants sought to honor Christ's prayer that we may all be one, when they took it as non-negotiable that they were part of various Protestant denominations which remained out of communion with Rome. The Catholic insistance that each Protestant who returns to Rome heals part of the Western schism is a nonstarter for this "ecumenism:" this "ecumenism" knows we need unity but takes schism as non-negotiable: which is to say that this "ecumenism" rejects the understanding of Orthodox, some Catholics, and even the first Protestants that full communion is full communion and what Christ prayed for was a full communion that assumed doctrinal unity.

One more thing that is very important to many Orthodox, and that I have never once heard acknowledged or even mentioned by the Catholics reaching so hard for ecumenical embrace is that many Orthodox are uneasy at best with ecumenism. It has been my own experience that the more devout and more mature Orthodox are, the more certainly they regard ecumenism as a spiritual poison. Some of the more conservative speak of "ecumenism awareness" as Americans involved in the war on drugs speak of "drug awareness."

Catholics can be a lot like Orthodox in their responses to Protestants and Protestant ideas of ecumenism; one might see a Catholic responding to an invitation to join an ecumenical communion service at First Baptist by saying something like,

I'm flattered by your ecumenical outreach... And really am, um, uh, honored that you see me as basically the same as an Evangelical... And I really appreciate that I am as welcome to join you in receiving communion as your very own flock... Really, I'm flattered...

...But full communion is full communion, and it reflects fundamental confusion to put the cart before the horse. For us to act otherwise would be a travesty. I know that you may be generously overlooking our differences, but even if it means being less generous, we need to give proper attention to our unresolved differences before anything approaching full communion would be appropriate.

But Catholics seem to be a bit like Protestants in their ecumenical advances to Orthodox. If I understand correctly, whereas Rome used to tell Orthodox, "You would be welcome to take communion with us, but we would rather you obey your bishops," now I am told by Rome that I may remain Orthodox while receiving Roman communion, and my reply is,

I'm flattered by your ecumenical outreach... And really am, um, uh, honored that you see me as basically the same as any Catholic... And I really appreciate that I am as welcome to join you in receiving communion as your very own flock... Really, I'm flattered...

...But full communion is full communion, and it reflects fundamental confusion to put the cart before the horse. For us to act otherwise would be a travesty. I know that you may be generously overlooking our differences, but even if it means being less generous, we need to give proper attention to our unresolved differences before anything approaching full communion would be appropriate.

If the Roman Church is almost Orthodox in its dealings with Protestants, it in turn seems almost Protestant in its dealings with Orthodox. It may be that Rome looks at Orthodoxy and sees things that are almost entirely permitted in the Roman Church: almost every point of theology or spirituality that is the only way to do things in Orthodoxy is at least a permitted option to Roman Catholics. (So Rome looks at Orthodoxy, or at least some Romans do, and see Orthodox as something that can be allowed to be a full-fledged part of the Roman communion: almost as Protestants interested in ecumenism look at the Roman Church as being every bit as much a full-fledged Christian denomination as the best of Protestant groups.) But the reverse of this phenomenon is not true: that is, Orthodox do not look at Rome and say, "Everything that you require or allow in spiritual theology is also allowed in healthy Eastern Orthodoxy." Furthermore, I have never seen awareness or sensitivity to those of Orthodox who do not consider ecumenism, at least between traditional communions, to be a self-evidently good thing to work for: Catholics can't conceive of a good reason for why Orthodox would not share their puppyish enthusiasm for ecumenism. And I have never heard a Catholic who expressed a desire for the restoration for full communion show any perception or willingness to work for the Orthodox concerns about what needs to feed into any appropriate restoration of communion, namely the recantation of Western heresy represented by figures like Thomas Aquinas and not only by Mater et Magistra or liberal Catholic dissent.

Conclusion: are we at the eve of an explosion?

I may have mentioned several elephants in the room. Let me close by mentioning one more that many Orthodox are painfully aware of, even if Catholics are oblivious.

Orthodoxy may remind Western Christians of Rome's ancient origins. But there is an important way in which I would compare Orthodoxy today to Western Christianity on the eve of the Reformation. Things hadn't exploded. Yet. But there were serious problems and trouble brewing, and I'm not sure it's that clear to people how much trouble is brewing.

Your ecumenical advances and efforts to draw us closer to Rome's enfolding bosom come at a rough and delicate time:

What if, while there was serious trouble but not yet schisms spreading like wildfire, the East had reached out to their estranged Western brethren and said:

Good news! You really don't need scholasticism... And you don't exactly need transsubstantiation either... And you don't need anywhere such a top-down Church heirarchy... And you really don't need to be in communion with the Patriarch of Rome... And...

There is a profound schism brewing in the Orthodox Church. It may not be within your power to stop it, but it may be within your power to avoid giving it an early start, and it may be within your power to avoid making the wreckage even worse.

The best thing I can think of to say is simply, "God have mercy on us all."

Cordially yours,

Christos Jonathan Seth Hayward

The Sunday of St. Mary of Egypt; Lent, 2009.

What Makes Me Uneasy About Fr. Seraphim (Rose) and His Followers

Uncomfortable and uneasy—the root cause?

Two out of many quotes from a discussion where I got jackhammered for questioning whether Fr. Seraphim is a full-fledged saint:

"Quite contrary, the only people who oppose [Fr. Seraphim's] teachings, are those who oppose some or all of the universal teachings of the Church, held by Saints throughout the ages. Whether a modern theologian with a 'PhD,' a 'scholar', a schismatic clergymen, a deceived layperson, or Ecumenist or rationalist - these are the only types of people you will find having a problem with Blessed Seraphim and his teachings."

You are truly desparate for fame. Guess what? Blessed Seraphim Rose will forever be more famous than you. Fitting irony I think, given that he never sought after fame. Ps. Willfully disrespecting a Saint of the Church is sacreligious. Grow up, you pompous twit."

There are things that make me uneasy about many of Fr. Seraphim (Rose)'s followers. I say many and not all because I have friends, and know a lovely parish, that is Orthodox today through Fr. Seraphim. One friend, who was going through seminary, talked about how annoyed he was, and appropriately enough, that Fr. Seraphim was always referred to as "that guy who taught the tollhouses." (Tollhouses are the subject of a controversial teaching about demonic gateways one must pass to enter Heaven.) Some have suggested that he may not become a canonized saint because of his teachings there, but that is not the end of the world and apparently tollhouses were a fairly common feature of nineteenth century Russian piety. I personally do not believe in tollhouses, although it would not surprise me that much if I die and find myself suddenly and clearly convinced of their existence: I am mentioning my beliefs, as a member of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia, and it is not my point to convince others that they must not believe in tollhouses.