- We stand in an arena, the great coliseum. For it is the apostles who were sent forth last, as if men condemned to die, made a spectacle unto the world, to angels and men.

- St. Job was made like unto a champion waging war against Satan, on God's behalf. He lost everything and remained God-fearing, standing as the saint who vindicated God.

- But all the saints vindicate God.

- We are told as we read the trials in the Book of Job that Satan stands slandering God's saints day and night and said God had no saint worthy of temptation. And the Lord God Almighty allowed Satan to tempt St. Job.

- We are told this, but in the end of the Scripture, even when St. Job's losses are repaid double, St. Job never hears. He never knows that he stands in the cosmic coliseum, as a champion on God's behalf. Never on earth does St. Job know the reason for the catastrophes that befell him.

- St. Job, buffeted and bewildered, could see no rhyme or reason in what befell him. Yet even the plagues of Satan were woven into the plans of the Lord God who never once stopped working all things to good for this saint, and to the saint who remained faithful, the plagues of Satan are woven into the diadem of royal priesthood crowning God's saints.

- Everything that comes to us is either a blessing from God or a temptation which God has allowed for our strengthening. The plagues by which Satan visited St. Job are the very means themselves by which God glorified his faithful saint.

- Do not look for God in some other set of circumstances. Look for him in the very circumstances you are in. If you look at some of your circumstances and say, "God could not have allowed that!", you are not rightly accepting the Lord's work in the circumstances he has chosen to work his glory.

- You are in the arena; God has given you weapons and armor by which to fight. A poor warrior indeed blames the weapons God has armed him with.

- Fight therefore, before angels and men. The circumstances of your life are not inadequate, whether through God lacking authority, or wisdom, or love. The very sword blows of Satan glancing off shield and armor are ordained in God's good providence to burnish tarnishment and banish rust.

- The Almighty laughs Satan to scorn. St. Job, faithful when he was stricken, unmasked the feeble audacity of the demons.

- God gives ordinary providence for easy times, and extraordinary providence for hard times.

- If times turn hard for men, and much harder for God's servants, know that this is ordained by God. Do not suppose God's providence came when you were young but not now.

- What in your life do you wish were gone so you could be where you should be? When you look for God to train you in those very circumstances, that is the beginning of victory. That is already a victory won.

- Look in every circumstance for the Lord to train you. The dressing of wounds after struggle is part of training, and so is live combat.

- The feeble audacity of the demons gives every appearance of power, but the appearance deceives.

- Nothing but your sins can wound you so that you are down. And even our sins are taken into the work of the Almighty if we repent.

- When some trial comes to you, and you thank God, that is itself a victory.

- Look for God's work here and now. If you will not let God work with you here and now, God will not fulfill all of your daydreams and then begin working with you; he will ask you to let him train you in the here and now.

- Do you find yourself in a painfully rough situation? Then what can you do to lighten others' burdens? Instead of asking, "Why me?", ask, "Why not me?"

- An abbot asked a suffering monk if he wanted the abbot to pray that his suffering be taken away. The disciple said, "No," and his master said, "You will outstrip me."

- It is not a contradiction to say that both God has designs for us, and we are under the pressure of trials. Diamonds are only made through pressure.

- No disciple is greater than his master. Should we expect to be above sufferings when the Son of God was made perfect through suffering?

- Anger is a spiritual disease. We choose the path of illness all the more easily when we do not recognize that God seeks to train us in the situation we are in, not the situation we wish we were in.

- It is easier not to be angry when we recognize that God knows what he is doing in the situations he allows us to be in. The situation may be temptation and trial, but was God impotent, unwise, or unloving in how he handled St. Job?

- We do not live in the best of all possible worlds by any means. We live instead in a world governed by the best of all possible Gods. And that is the greater blessing.

- Some very holy men no longer struggle spiritually because spiritual struggle has worked out completely. But for the rest of us, struggle is a normal state. It is a problem for you or I to pass Lent without struggle. If we struggle and stumble and fall, that is good news. All the better if we cannot see how the thrusts and blows of the enemy's sword burnish away a little rust, one imperceptible speck at a time.

- Do you ask, "Did it have to hurt that much?" When I have asked that question, I have not found a better answer than, "I do not understand," and furthermore, "Do I understand better than God?"

- We seek happiness on terms that make success and happiness utterly impossible. God destroys our plans so that we might have the true happiness that is blessedness.

- Have a good struggle.

- There is no road to blessedness but the royal road of affliction that befits God's sons. Consider it pure joy when you fall into different trials and temptations. If you have trouble seeing why, read the Book of James.

- Treasures on earth fail. Treasures in Heaven are more practical.

- Rejoice and dance for joy when men slander you and revile you and curse you for what good you do. This is a sign you are on the royal road; this is how the world heralds prophets and sons of God. This earthly dishonor is the seal of Heavenly honor.

- If you have hard memories, they too are a part of the arena. Forgive and learn to thank God for painful memories.

- Remember that you will die, and live in preparation for that moment. There is much more life in mindfully dying each day than in heedlessly banishing from your mind the reality. Live as men condemned to die, made a spectacle before men and angels.

- Live your life out of prayer.

- It takes a lifetime of faith to trust that God always answers prayers: he answers either "Yes, here is what you asked," or "No, here is something better." And to do so honestly can come from the struggle of praying your heart out and wondering why God seemed to give no answer and make no improvements to your and others' pain.

- In the Bible, David slew Goliath. In our lives, David sometimes prevails against Goliath, but often not. Which is from God? Both.

- Struggling for the greater good is a process of at once trying to master, and to get oneself out of the way. Struggle hard enough to cooperate with God when he rips apart your ways of struggling to reach the good.

- Hurting? What can you do to help others?

Apps and Mobile Websites for the Orthodox Christian Smartphone and Tablet: Best iPhone, iPad, Droid, Samsung, Android, Kindle, and Blackberry Mobile Websites and Apps

Apps that are directly useful for ascesis

There are not many apps formally labeled as Orthodox Christian, but there are some apps and mobile websites that can be used in the pursuit of the spiritual discipline of ascesis. Among these apps are:

- Ancient Faith Radio

- The value of this app goes more or less without saying, but there is one caveat.

I visited a monastery whose rules included not playing recorded music, and I saw outside the nave an old man, with headphones on, listening to Byzantine chant, moving to its beat and off in his own world.

It struck me, if anything, as an act beneath the dignity of an old man. Being off in your own world is not good for anyone, but there are some things tolerated in youth that are just sad in a mature adult. And as best I can surmise the rule was not a rule against certain types of prohibited music (though acid rock would be a worse violation), but using technology to be off in your own world in the first place. And it is because of this that I rarely listen to recorded liturgical music: it is easily available, but there is something about it that is simply wrong. (And this is not just a matter of how digital music sounds to someone with perfect pitch.)

I know of nothing better in terms of Orthodox Internet radio than Ancient Faith Radio, and really have very little if anything to say how Ancient Faith Radio could better do the job of a radio station (or, as the case may be, two stations providing access to lectures, sacred liturgical chant, and access to past broadcasts). But I have some reservations about why Orthodox need to be doing the job of a radio station—as, for that matter, I have a cautious view of my own website. The ironically titled The Luddite's Guide to Technology lays out the attitude where a radio station with crisply rendered sacred song available on one's iPhone or Android should be used that much.

- CJSHayward.com/psalms/?mode=mobile (bookmark for iPhone, iPad, Droid, Samsung, Android, Kindle, and Blackberry; tablet users may prefer CJSHayward.com/psalms/)

- The Psalter is the greatest prayerbook of the Orthodox Church. This page selects a Psalm at random, until you click a link and it provides another Psalm at random. They seem to be helpful, chiefly because the Psalter is helpful.

- The Kindle app for iPhone, iPod Touch, Droid, Samsung, Android, and Blackberry (not to mention PC's)

- I wouldn't want to denigrate paperback books, but you can buy some of the greatest classics on Kindle: the Orthodox Study Bible (an edition I discussed in my Orthodox bookshelf), the Philokalia, and My Orthodox Prayer Book. Plenty of lesser works are available too: see my own Kindle offerings at CJSHayward.com.

- Wants and Needs

- Having this app is a want and not a need, but there are legitimate wants.

This is a simple but very well-executed app to help appreciate what are our wants, what are our needs, and what we have to be grateful for.

Apps that are generally useful

G.K. Chesterton said, "There is more simplicity in the man who eats caviar on impulse than the man who eats grape-nuts on principle." And there is more Orthodoxy in just using an iPhone as a tool for being human than going to the app store and looking for apps endorsed as religious.

Do a Google search for best iPhone apps, for instance, and you will find a wealth of app recommendations. And many of these can work as a support for an Orthodox life of ascesis: Orthodoxy did not invent the pot, the belt, or the hammer, and yet all of these can have a place. Not, perhaps, the same place as a book of prayers, but a legitimate place. Secular tools and activities are holy when they are used by a life out of ascesis. And there are some excellent apps; among them I would name PocketMoney, a personal finance tool;mSecure, a password manager; Things, a to-do list; GPS MotionX Drive, a navigation tool; Flashlight, which lets you use the LED as a flashlight; and the main Google app, a search app optimized for the web by the company that defined search. All of these have their place.

But there are many apps on those lists that are unhelpful. Games and entertainment apps are meant to kill time, which is to say that they are meant to provide a convenient alternative to the spiritual discipline that tolds monks, "Your cell [room] will teach you everything you need to know." And I suggest asking, in considering an app, "Does this support ascesis?" A to-do list helps with nuts and bolts of a disciplined life. An app to show a stream of new and different restaurants feeds gluttony. It is fine for Orthodox Christians to use apps that are not branded as Orthodox or ascetical, but the question "Does this support ascetical living?" (which is in no way a smartphone-centric question, but a basic question of Orthodox life, to be settled with one's priest or spiritual father perhaps), applies here.

A closing note: When do you call 9-1-1 (or 9-9-9)?

There is a good case to be made that the most important number for you to be able to call on any phone is 9-1-1. However, this does not mean that your first stop in dealing with boredom is to call 9-1-1 to just chat with someone. It may be the most important number for you to be able to call—and the only number that may save your life—but using 9-1-1 rightly means using it rarely.

I would not speak with quite equal force about smartphones, but I would say that if you really want to know how to use your smartphone in a way that supports Orthodox spiritual discipline, the biggest answer is not to use one more app or one more mobile website. It is to use your phone less, to visit people face to face instead of talking and texting, and to use apps a little more like you use 9-1-1: to get a specific task accomplished.

And this is without looking at the problem of an intravenous drip of noise. The iPhone and Android's marketing proposition is to deliver noise as an anaesthetic to boredom. And Orthodox use of the iPhone is not to deliver noise: all of us, with or without iPhones or Android devices, are to cultivate the ascesis of silence, and not make ourselves dependent on noise. And it is all too easy with these smartphones; they are designed so that it is too easy.

The Fathers did not say "You cannot kill time without injuring eternity," but on this point they could have. Killing time is the opposite of the ascesis of being present, of being attentive of the here and now that God has given us, and not the here and now that we wish to be in or the here and now we hope to get to. Contentment and gratitude are for here now, not what we imagine as better conditions. We are well advised to live astemeniously, and that is where the best use of iPhone and Android smartphones and tablets comes from.

Smartphones have many legitimate uses, but don't look to them for, in modern terms, a mood management tool.

Animals

Can you pull out Leviathan with a hook,

or press his tongue down with a cord?

Can you put a rope in his nose,

or pierce his jaw with a hook?

Will he make many supplications to you?

Will he speak soft words to you?

Will he make a covenant with you?

Will he be your servant forever?

Will you play with him as with a bird?

Or will you put him on a rope for your maidens?

Will traders bargain for him?

Shall he be divided among the merchants?

Can you fill his skin with harpoons,

or his head with fishing spears?

Lay hands on him;

Think of the battle; you will not do it again!

Behold, the hope of a man is disappointed;

he is laid low even at the sight of him.

No one is so fierce as to dare to stir him up.

Who then is he who can stand before him?

Who can confront him and be safe?

Under the whole Heavens, who?

I will not keep silence concerning his limbs,

or his mighty strength, or his powerful frame.

Who can strip off his outer garment?

Who can penetrate his double coat of mail?

Who can open the doors of his face?

Round about his teeth is terror.

His back is made of rows of shields,

shut up as tightly as with a seal.

One is so near to another

that no air can pass between them.

They are joined to one another;

they clasp each other and cannot be separated.

His sneezings flash forth light;

and his eyes are like the eyelids of the dawn.

Out of his mouth go flaming torches;

sparks of fire leap forth.

Out of his nostrils comes forth smoke,

as from a boiling pot and burning rushes.

In his neck abides strength,

and terror dances before him.

The folds of his flesh cleave together,

firmly cast upon him and immovable.

His heart is as hard as a stone,

as hard as the lower millstone.

When he raises himself up, the gods are afraid;

at the crashing they are beside themselves.

Though the sword reaches him, it does not avail;

nor spear, nor dart, nor javelin.

He counts iron as straw,

and bronze as rotted wood.

The arrow cannot make him flee;

for him slingstones are turned to rubble.

Clubs are counted as stubble;

he laughs at the rattle of javelins.

His underparts are like sharp potsherds;

he spreads himself like a threshing sledge on the mire.

He makes the deep boil like a pot;

he makes the sea like a pot of ointment.

Behind him he leaves a shining wake;

one would think the deep to be hoary.

Upon earth there is not his equal,

a creature without fear.

He beholds everything that is high;

he is king over all of the sons of pride. (Job 41)Behold Behemoth, which I made with you;

he eats grass as an ox.

Look now; his strength is in his loins,

and his power is in the muscles of his belly.

He swings his tail like a cedar;

the sinews of his thighs are knit together.

His bones are like rods of bronze;

his limbs are like bars of iron.

He is the chief of the works of God;

his maker can approach him with the sword.

Surely the mountains bring forth food to him,

where all of the beasts of the field play.

He lies under the lotus trees;

the willows of the book surround him.

Behold, he drinks up a river and is not frightened;

he is confident though the Jordan rushes into his mouth.

Can a man take him with hooks,

or pierce his nose with a snare? (Job 40:15-24)

These words, lightly altered from the Revised Standard Version, culminate a divine answer to Job out of the whirlwind: where was Job when God laid the foundation of earth? The divine voice turns to the foundations of the earth and the bounds of the sea, light and darkness, rain and hail, the stars, and the lion, mountain goat, wild ox and ass, ostrich, horse, and the hawk. The text is powerful even if translators demurely use "tail" for what the Behemoth swings like a cedar.

On a more pedestrian level, I was reticent when some friends had told me that they were going to be catsitting in their apartment and invited me over. (They know I love cats and other animals.) What I thought to explain later was that I proportionately outweigh a housecat by about as much as a mammoth outweighs me (perhaps "rhinoceros" would have been more appropriately modest than "mammoth"), and I try to let animals choose the pace at which they decide I'm not a threat. (And the cat has no way of knowing I don't eat cats.) As far as the environment to meet goes, I didn't bring up "You never get a second chance to make a first impression," but humans are more forgiving than animals. Although I didn't mention that, I did mention the difference between someone approaching you in a mailroom and someone following you in a less safe place. All of which was to explain why I love animals but would be cautious about approaching a cat in those circumstances and would play any visit by ear. (I later explained how even if the cat is not sociable and spends most of its visit hiding, they can still experience significant success by returning the cat to his owner unharmed with any unpleasantness quickly forgotten in the arms of his owner.)

As I write, I spent a lovely afternoon with those friends, and tried to serve as a tour guide. What I realized as I was speaking to them was that I was mixing the scientific with what was not scientific, not exactly by saying things some scientists would disapprove like why eyeless cave fish suggest a reason natural selection might work against the formation of complex internal and external organs, but by something else altogether.

What is this something else? It is the point of this essay to try and uncover that.

I wrote in Meat why I eat lots of beef but am wary of suffering caused by cruel farming, and for that reason don't eat veal and go light on pork: I believe it is legitimate to kill animals for food but not moral to raise them under lifelong cruelty to make meat cheap. (Jesus was very poor by American standards and rarely had the luxury of eating meat.) While I hope you will bookmark Meat and consider trying to eat lower on the animal cruelty scale, my reason for bringing this up is different. The reason I wrote Meat has to do with something older in my life than my presently being delighted to find beef sausage and beef bacon, and trying not to eat much more meat than I need. And I am really trying hard not to repeat what I wrote before.

Thomas Aquinas is reported to have said that the one who does not murder because "Do not murder" is so deep in his bones that he needs no law to tell him not to murder, is greater than the theologian who can derive that law from first principles. What I want to talk about is simultaneously "deep in the bones" knowledge and something I would like to discover, and it is paradoxically something I want to discover because it is deep in my bones. And it is connected in my minds less to meat than when one of my friends, having come with a large dog who was extremely skittish around men, had a mix of both women and men over to help her move into her apartment, and asked me and not any of the women to take care of a dog she acknowledged was afraid of men. (I don't know why she did this; I don't think she thought about my being a man.) At the beginning of half an hour, the dog was manifestly not happy at being at the other end of a leash with me; at the end of the half hour the dog had his head in my lap and was wagging his tail to meet the other men as well as women.

Part of this was knowledge in the pure Enlightenment sense about stretching an animal's comfort zone without pushing it into panic—a large part, in fact. But another part is that while I don't believe that animals are people, I try to understand animals and relate to them the same way I understand and relate to people. Maybe I can't discuss philosophy with a rabbit, and maybe a little bit of knowledge science-wise helps about minimizing intimidation to a creature whose main emotion is fear.

But that's not all.

After I ended the phone conversation where I explained why I was wary of terrifying what might be an already afraid cat, I realized something. I had just completed a paper for a feminist theology class which criticized historical scholarship that looked at giants of the past as behaving strangely and inexplicably, and I tried to explain why their behavior was neither strange nor inexplicable. I suggested that historical sources need to be understood as human and said that if you don't understand why someone would write what you're reading, that's probably a sign there's something you don't understand. Most of the length of my paper went into trying to help the reader see where the sources were coming from and see why their words were human, and neither strange nor inexplicable. What I realized after the phone conversation was that I had given the exact same kind of argument for why I was hesitant to introduce myself to the cat: I later called and suggested that the cat spend his first fifteen minutes in the new apartment with his owner petting him. I never said that the cat was human, and unlike some cat owners I would never say that the cat was equal to a human, but even if I will never meet that cat, my approach to dealing with the cat meet him is not cut off from my approach to dealing with people. And in that regard I'm not anywhere near a perfect Merlin (incidentally, a merlin is a kind of hawk, the last majestic creature we encounter before the proud Behemoth and Leviathan, and it does not seem strange to me that a lot of Druids have hawk in their name, nor do I think the name grandiose), but Merlin appears in characters' speculation in C.S. Lewis's That Hideous Strength as someone who achieves certain effects, not by external spells, but by who he is and how he relates to nature. That has an existentialist ring I'd like to exorcise, but if I can get by with saying that I feel no need to meditate in front of a tree and repeat a mantra of "I see the tree. The tree sees me," nor do I spend much of any time trying to "Get in touch with nature..." then after those clarifications I think I can explain why something of Lewis's portrayal of Merlin resonates. (And I don't think it's the most terribly helpful approach to talk about later "accretions" and try to understand Arthurian legend through archaeological reconstruction of 6th century Britain; that's almost as bad as asking astronomy to be more authentic by only using the kind of telescopes Galileo could use.) It is not the scientific knowledge I can recite that enables me to relate to animals well, but by what is in my bones: a matter of who I am even before woolgathering about "Who am I?"

This has little to do with owning pets; I do not know that I would have a pet whether or not my apartment would allow them, and have not gone trotting out for a cat fix even though one is available next door. It's not a matter of having moral compunctions about meat, although it fed into my acquiring such compunctions a few years ago. It's not about houseplants either; my apartment allows houseplants but I have not gone to the trouble of buying one. Nor is it a matter of learning biology; physics, math, and computer science were pivotally important to me, but not only was learning biology never a priority for my leisure time, but I am rather distressed that when people want to understand nature they inevitably grab for a popular book on biology. When people try to understand other people, do they ask for CT scan of the other person's brain? Or do they recognize that there is something besides biological and medical theories that can lend insight into people and other creatures?

The fact that we do not try to relate to people primarily through medicine suggests a way we might relate to other animals besides science: trying to relate to nature by understanding science is asking an I-It tree to bear I-Thou fruit. (If you are unfamiliar with Martin Buber's I and Thou, it would also be comparable to asking a stone to lay an egg.)

I'm not going to be graphic, but I would like to talk about dissection. Different people respond differently to different circumstances, and I know that my experience with gradeschool dissection is not universal. I also know that dissection is not a big deal for some people, as I know that the hunters I know are among the kindest people I've met. Still I wish to make some remarks.

The first thing is that there is an emotional reaction you people need to suppress. Perhaps some adults almost reminisce about that part of their education as greatly dreaded but almost disappointing in its lack of psychological trauma. And I may be somewhat sensitive. But there's something going on in that experience, stronger for some people and weaker in others. It's one learning experience among others and what is learned is significant.

But is it really one learning experience among others?

Again without being graphic, dissection could have been used as a bigger example in C.S. Lewis's The Abolition of Man, a book I strongly reccommend. It finds a red flag in the dissection room, if mentioned only briefly—a red flag that something of our humanity is being lost.

To be slightly more graphic, one subtle cue was that in my biology classroom, there were plenty of gloves to begin with, then as the dissections progressed, only one glove per person, then no gloves at all—at a school for the financially gifted. And, to note something less subtle, the animals were arranged in a very specific order. You could call the progression, if you wanted to, the simplest and least technical to properly dissect, up to a last analysis which called for distinctly more technical skill. Someone more suspicious might point out how surprisingly the list of animals coincides with what a psychologist would choose in order to desensitize appropriately sensitive children. I really don't think I'm being too emotional by calling this order a progression from what you'd want to step on to what some people would want to cuddle. I don't remember the Latin names I memorized to make sense of what I was looking at. What it did to my manhood, or if you prefer humanity, is lasting, or at least remembered. Perhaps my sensibilities might have needed to be coarsened, but it is with no great pride that I remember forcing myself in bravado to dissect without gloves even when everybody else was wearing them. Perhaps I crossed that line so early because there were other lines that had already been crossed in me. And perhaps I am not simply being delicate, but voicing a process that happened for other people too.

If the question is, "What do we need in dealing with animals?", one answer might be, "What dissection makes children kill." I'm not talking about the animals, mind you; with the exception of one earthworm, I never killed a specimen. Perhaps the memories would be more noxious if I had, but all my specimens were pre-killed and I was not asked to do that. But even with pre-killed specimens I was, in melodramatic terms, ordered to kill something of my humanity. I do not mean specifically that I experienced unpleasant emotions; I've had a rougher time with many things I can remember with no regrets. What I mean is that any emotions were a red flag that something of an appropriate way of relating to animals was being cut up with every unwanted touch of the scalpel. It's not just animals that are dismantled in the experience.

When I wrote my second novel, I wrote to convey medieval culture (perhaps Firestorm 2034 would have been better if I focused more on, say, telling a story), and one thing I realized was that I would have an easier time conveying medieval culture if I showed its contact, in a sense its dismantling, with a science fiction setting, although I could have used the present day: I tried not to stray too far from the present day U.S. There is something that is exposed in contact with something very different. It applies in a story about a medieval wreaking havoc in a science fiction near future. It also applies in the dissection room. Harmony with nature, or animals, may not be seen in meditating in a forest. Or at least not as clearly as when we are fighting harmony with animals as we go along with an educator's requests to [graphic description deleted].

Let me return to the account from which I took words about a Leviathan and a Behemoth whose tail swings like a cedar. This seemingly mythological account—if you do not know how Hebrew poetry operates, or that a related languages calls the hippopotamuspehemoth instead of using the Greek for "river horse" as we do—is better understood if you know what leads up to it. A stricken Job, slandered before God as only serving God as a mercenary, cries out to him in anguish and is met by comforters who tell him he is being punished justly. The drama is more complex than that, but God save me from such comforters in my hour of need. The only thing he did not rebuke the comforters for was sitting with Job in silence for a week because they saw his anguish was so great.

Job said, "But I would speak to the Almighty, and I desire to argue my case with God." (Job 13:3) And, after heated long-winded dialogue, we read (Job 38-39, RSV):

Then the Lord answered Job out of the whirlwind:

"Who is this that darkens counsel by words without knowledge?

Gird up your loins like a man,

I will question you, and you shall declare to me.

Where were you when I laid the foundation of the earth?

Tell me, if you have understanding.

Who determined its measurements—surely you know!

Or who stretched the line upon it?

On what were its bases sunk,

or who laid its cornerstone,

when the morning stars sang together,

and all the sons of God shouted for joy?

Or who shut in the sea with doors,

when it burst forth from the womb;

when I made clouds its garment,

and thick darkness its swaddling band,

and prescribed bounds for it,

and set bars and doors,

and said, `Thus far shall you come, and no farther,

and here shall your proud waves be stayed'?

Have you commanded the morning since your days began,

and caused the dawn to know its place,

that it might take hold of the skirts of the earth,

and the wicked be shaken out of it?

It is changed like clay under the seal,

and it is dyed like a garment.

From the wicked their light is withheld,

and their uplifted arm is broken.

Have you entered into the springs of the sea,

or walked in the recesses of the deep?

Have the gates of death been revealed to you,

or have you seen the gates of deep darkness?

Have you comprehended the expanse of the earth?

Declare, if you know all this.

Where is the way to the dwelling of light,

and where is the place of darkness,

that you may take it to its territory

and that you may discern the paths to its home?

You know, for you were born then,

and the number of your days is great!

Have you entered the storehouses of the snow,

or have you seen the storehouses of the hail,

which I have reserved for the time of trouble,

for the day of battle and war?

What is the way to the place where the light is distributed,

or where the east wind is scattered upon the earth?

Who has cleft a channel for the torrents of rain,

and a way for the thunderbolt,

to bring rain on a land where no man is,

on the desert in which there is no man;

to satisfy the waste and desolate land,

and to make the ground put forth grass?

Has the rain a father,

or who has begotten the drops of dew?

From whose womb did the ice come forth,

and who has given birth to the hoarfrost of heaven?

The waters become hard like stone,

and the face of the deep is frozen.

Can you bind the chains of the Plei'ades,

or loose the cords of Orion?

Can you lead forth the Maz'zaroth in their season,

or can you guide the Bear with its children?

Do you know the ordinances of the heavens?

Can you establish their rule on the earth?

Can you lift up your voice to the clouds,

that a flood of waters may cover you?

Can you send forth lightnings, that they may go

and say to you, `Here we are'?

Who has put wisdom in the clouds,

or given understanding to the mists?

Who can number the clouds by wisdom?

Or who can tilt the waterskins of the heavens,

when the dust runs into a mass

and the clods cleave fast together?

Can you hunt the prey for the lion,

or satisfy the appetite of the young lions,

when they crouch in their dens,

or lie in wait in their covert?

Who provides for the raven its prey,

when its young ones cry to God,

and wander about for lack of food?

Do you know when the mountain goats bring forth?

Do you observe the calving of the hinds?

Can you number the months that they fulfil,

and do you know the time when they bring forth,

when they crouch, bring forth their offspring,

and are delivered of their young?

Their young ones become strong, they grow up in the open;

they go forth, and do not return to them.

Who has let the wild ass go free?

Who has loosed the bonds of the swift ass,

to whom I have given the steppe for his home,

and the salt land for his dwelling place?

He scorns the tumult of the city;

he hears not the shouts of the driver.

He ranges the mountains as his pasture,

and he searches after every green thing.

Is the wild ox willing to serve you?

Will he spend the night at your crib?

Can you bind him in the furrow with ropes,

or will he harrow the valleys after you?

Will you depend on him because his strength is great,

and will you leave to him your labor?

Do you have faith in him that he will return,

and bring your grain to your threshing floor?

The wings of the ostrich wave proudly;

but are they the pinions and plumage of love?

For she leaves her eggs to the earth,

and lets them be warmed on the ground,

forgetting that a foot may crush them,

and that the wild beast may trample them.

She deals cruelly with her young, as if they were not hers;

though her labor be in vain, yet she has no fear;

because God has made her forget wisdom,

and given her no share in understanding.

When she rouses herself to flee,

she laughs at the horse and his rider.

Do you give the horse his might?

Do you clothe his neck with strength?

Do you make him leap like the locust?

His majestic snorting is terrible.

He paws in the valley, and exults in his strength;

he goes out to meet the weapons.

He laughs at fear, and is not dismayed;

he does not turn back from the sword.

Upon him rattle the quiver,

the flashing spear and the javelin.

With fierceness and rage he swallows the ground;

he cannot stand still at the sound of the trumpet.

When the trumpet sounds, he says `Aha!'

He smells the battle from afar,

the thunder of the captains, and the shouting.

Is it by your wisdom that the hawk soars,

and spreads his wings toward the south?

Is it at your command that the eagle mounts up

and makes his nest on high?

On the rock he dwells and makes his home

in the fastness of the rocky crag.

Thence he spies out the prey; his eyes behold it afar off.

[closing gruesome image deleted]

Then Job says some very humble and humbled words. Then the Lord gives his coup de grace, a demand to show strength like God that culminates with words about the Leviathan and Behemoth. Job answers "... Therefore I have uttered what I did not understand, things too wonderful for me, which I did not know... I had heard of thee by hearing of the ear, but now my eye sees thee." (Job 42:3,5, RSV)

Did God blast Job like a soup cracker?

Absolutely, but if that is all you have to say about the text, you've missed the text.

There's something about Job's "comforters" defending a sanitized religion too brittle to come to terms with un-sanitized experience and un-sanitized humanity; Job cares enough about God to show his anger, and though he is never given the chance to plead his case before God, he meets God: he is not given what he asks for, but what he needs.

There's a lot of good theology about God giving us what we need, but without exploring that in detail, I would point out that the Almighty shows himself Almighty through his Creation, quite often through animals. There may be reference to rank on rank of angels named as all the sons of God shouting for joy (Job 38:7), but man is curiously absent from the list of majestic works; the closest reference to human splendor is "When [Leviathan] raises himself up the gods are afraid; at the crashing they are beside themselves" (Job 41:25). The RSV thoughtfully replaces "gods" with "mighty" in the text, relegating "gods" to a footnote—perhaps out of concern for readers who mihgt be disturbed by the Old and New Testament practice of occasionally referring to humans as gods, here in order to to emphasize that even the mightiest or warriors are terrified by the Leviathan.

This is some of the Old Testament poetry at its finest, written by the Shakespeare of the Old Testament, and as Hebrew poetry it lays heavy emphasis on one the most terrifying creature the author knew of, the crocodile, a terrifying enough beast that Crocodile Dundee demonstrates his manhood to the audience by killing a crocodile—and the film successfully competes head-to-head against fantasy movies that leave nothing to the imagination for a viewer who wants to see a fire-breathing dragon.

Let me move on to a subtle point made in Macintyre's Dependent Rational Animals: Why Human Beings Need the Virtues. While the main emphasis of the work is that dependence is neither alien to being human nor something that makes us somehow less than human, he alludes to the classical definition of man as "rational mortal animal" and makes a subtle point.

Up until a few centuries ago the term "animal" could be used in a sense that either included or excluded humans. While both senses coexisted, there was not a sense that calling a person an animal was degrading any more than it was degrading to mention that we have bodies. Now calling someone an animal is either a way of declaring that they are beneath the bounds of humanity, or a dubious compliment to a man for boorish qualities, or else an evolutionary biologist's way of insisting that we are simply one animal species among others, in neo-Darwinist fashion enjoying no special privilege. But Aristotle meant none of these when he recognized we are animals.

To be human is to be both spirit and beast, and not only is there not shame in that we have bodies that need food and drink like other animals, but there is also not shame in a great many other things: We perceive the world and think through our bodies, which is to say as animals. We communicate to other people through our bodies, which is to say as animals. Were we not animals the Eucharist would be impossible for Christians to receive. We are also spirit, and our spirit is a much graver matter than our status as animals, including in Holy Communion; our spirit is to be our center of gravity, and our resurrection body is to be transformed to be spiritual. But the ultimate Christian hope of bodily resurrection at the Lord's return is a hope that as spiritual animals we will be transfigured and stand before God as the crowning jewel of bodily creation. The meaning of our animal nature will be changed and profoundly transformed, but never destroyed. Nor should we hope to be released from being animals. To approach Christianity in the hope that it will save us from our animal natures—being animals—is the same kind of mistake as a child who understandably hopes that growing up means being in complete control of one's surroundings. Adulthood and Christianity both bring many benefits, but that is not the kind of benefit Christianity provides (or adulthood).

If that is the case, then perhaps there is nothing terribly provocative about my trying to understand other animals the way I understand other people. Granted, the understanding cannot run as deep because no other animal besides man is as deep as man and some would have it that man is the ornament of both visible and spiritual creation, Christ having become man and honored animal man in an honor shared by no angel. The old theology as man as microcosm, shared perhaps with non-Christian sources, sees us as the encapsulation of the entire created order. Does this mean that there are miniature stars in our kidneys? It is somewhat beside the point to underscore that every carbon nucleus in your body is a relic of a star. A more apropos response would be that to be human is to be both spirit and matter, to share life with the plants and the motion of animals, and that it is impossible to be this microcosm without being an animal. God has honored the angels with a spiritual and non-bodily creation, but that is not the only honor to be had.

In my homily Two Decisive Moments, I said,

In the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost. Amen.

There is a classic Monty Python "game show": the moderator asks one of the contestants the second question: "In what year did Coventry City last win the English Cup?" The contestant looks at him with a blank stare, and then he opens the question up to the other contestants: "Anyone? In what year did Coventry City last win the English Cup?" And there is dead silence, until the moderator says, "Now, I'm not surprised that none of you got that. It is in fact a trick question. Coventry City has never won the English Cup."

I'd like to dig into another trick question: "When was the world created: 13.7 billion years ago, or about six thousand years ago?" The answer in fact is "Neither," but it takes some explaining to get to the point of realizing that the world was created 3:00 PM, March 25, 28 AD.

Adam fell and dragged down the whole realm of nature. God had and has every authority to repudiate Adam, to destroy him, but in fact God did something different. He called Noah, Abraham, Moses, and Elijah, and in the fullness of time he didn't just call a prophet; he sent his Son to become a prophet and more.

It's possible to say something that means more than you realize. Caiaphas, the high priest, did this when he said, "It is better that one man be killed than that the whole nation perish." (John 11:50) This also happened when Pilate sent Christ out, flogged, clothed in a purple robe, and said, "Behold the man!"

What does this mean? It means more than Pilate could have possibly dreamed of, and "Adam" means "man": Behold the man! Behold Adam, but not the Adam who sinned against God and dragged down the Creation in his rebellion, but the second Adam, the new Adam, the last Adam, who obeyed God and exalted the whole Creation in his rising. Behold the man, Adam as he was meant to be. Behold the New Adam who is even now transforming the Old Adam's failure into glory!

Behold the man! Behold the first-born of the dead. Behold, as in the icon of the Resurrection, the man who descends to reach Adam and Eve and raise them up in his ascent. Behold the man who will enter the realm of the dead and forever crush death's power to keep people down.

Behold the man and behold the firstborn of many brothers! You may know the great chapter on faith, chapter 11 of the book of Hebrews, and it is with good reason one of the most-loved chapters in the Bible, but it is not the only thing in Hebrews. The book of Hebrews looks at things people were caught up in, from the glory of angels to sacrifices and the Mosaic Law, and underscores how much more the Son excels above them. A little before the passage we read above, we see, "To which of the angels did he ever say, 'You are my son; today I have begotten you'?" (Hebrews 1:5) And yet in John's prologue we read, "To those who received him and believed in his name, he gave the authority to become the children of God." (John 1:9) We also read today, "To which of the angels did he ever say, 'Sit at my right hand until I have made your enemies a footstool under your feet?'" (Hebrews 1:13) And yet Paul encourages us: "The God of peace will shortly crush Satan under your feet," (Romans 16:20) and elsewhere asks bickering Christians, "Do you not know that we will judge angels?" (I Corinthians 6:3) Behold the man! Behold the firstborn of many brothers, the Son of God who became a man so that men might become the Sons of God. Behold the One who became what we are that we might by grace become what he is. Behold the supreme exemplar of what it means to be Christian.

Behold the man and behold the first-born of all Creation, through whom and by whom all things were made! Behold the Uncreated Son of God who has entered the Creation and forever transformed what it means to be a creature! Behold the Saviour of the whole Creation, the Victor who will return to Heaven bearing as trophies not merely his transfigured saints but the whole Creation! Behold the One by whom and through whom all things were created! Behold the man!

Pontius Pilate spoke words that were deeper than he could have possibly imagined. And Christ continued walking the fateful journey before him, continued walking to the place of the Skull, Golgotha, and finally struggled to breathe, his arms stretched out as far as love would go, and barely gasped out, "It is finished."

Then and there, the entire work of Creation, which we read about from Genesis onwards, was complete. There and no other place the world was created, at 3:00 PM, March 25, 28 AD. Then the world was created.

To the Orthodox, at least in better moments, Christ is not just our perfect image of what it means to be God. He is also the definition of what it means to be Christian and what it ultimately means to be man.

Can we understand this and deny that Christ is an animal?

Ajax without JavaScript or Client-Side Scripting

The Ajax application included in this page implements a legitimate, if not particularly useful or even usable, "proof of concept" with partial page updates based on server communication. It accepts a string, and then lets you click on one of a few buttons to see that string styled the way the button is styled, appending a link from the server. But it demonstrates one interesting feature:

It works just the same if you turn off JavaScript and any other client-side scripting completely.

How does it work?

Ajax partial page updates don't need to manipulate a monolithic page's DOM; the reason browser back buttons work in Gmail is an invisible, seamless use of iframes that create browser history. And not only can you do partial page updates via iframes without DOM manipulation, you can do it without client side scripting.

The source code to the server is available here, but it is simple, stateless, and doesn't really hold any secrets; it could be fairly well reconstructed simply by observing what is going on in the demo app above. The basic insight is that a webpage that talks to a server and makes partial updates can be made by the usual Ajax tools, but at least a basic proof of concept can be made with old HTML features like frames and iframes, links and targets, forms, and meta refresh.

This Ajaxian use of old web technologies may or may not produce graceful alternatives to standard Ajax techniques, either alone or in a "progressive enhancement"/"graceful degradation" strategy, but it may allow graceful degradation to be just a little more graceful, and JAWS might at least know when something on the sceen has changed. But here is a proof of concept that it is possible to implement a webapp with partial page updates and server communications that works in a browser that has JavaScript and any other client-side scripting turned off.

AI as an Arena for Magical Thinking Among Skeptics

Surgeon General's Warning

This piece represents my first serious study as an Orthodox Christian. The gist of it, by which I mean a critique of the artificial intelligence and cognitive science movement whose members are convinced of its progress for reasons unrelated to any real achievement of its core goal, is one I would still maintain. Artificial intelligence, over a decade after the thesis was written, remains "just around the corner since 1950". The core pioneer John von Neumann's The Computer and the Brain's core assertion that the basis of human thought is "add, subtract, multiply, and divide" remains astonishingly naïve to the point of being crass.

With that much stated, there are things that don't belong. The "I-Thou" existentialism is not of Orthodox origin and its study of occult aspects is simply inappropriate. I do not say inaccurate, only wrong. I believe there is probably some truth to some suggestion that the artificial intelligence endeavor represents a recurrence of age-old occult dreams dressed in the clothing of computer science and secular rationality. Such things should still not have been studied, or at very least not by me.

For those still interested, my dissertation is below.

AI as an Arena for Magical Thinking Among Skeptics

Artificial intelligence, cognitive science, and Eastern Orthodox views on personhood

M.Phil. Dissertation

CJS Hayward

christos.jonathan.hayward@gmail.com

CJSHayward.com

15 June 2004

Table of Contents

Abstract

Introduction

Artificial Intelligence

The Optimality Assumption

Just Around the Corner Since 1950

The Ghost in the Machine

Occult Foundations of Modern Science

Renaissance and Early Modern Magic

Science, Psychology, and Behaviourism

I-Thou and Humanness

Orthodox Anthropology in Maximus Confessor's Mystagogia

Intellect and Reason

Intellect, Principles, and Cosmology

The Intelligible and the Sensible

Knowledge of the Immanent

Intentionality and Teleology

Conclusion

Epilogue

Bibliography

Abstract

I explore artificial intelligence as failing in a way that is characteristic of a faulty anthropology. Artificial intelligence has had excellent funding, brilliant minds, and exponentially faster computers, which suggests that any failures present may not be due to lack of resources, but arise from an error that is manifest in anthropology and may even be cosmological. Maximus Confessor provides a genuinely different background to criticise artificial intelligence, a background which shares far fewer assumptions with the artificial intelligence movement than figures like John Searle. Throughout this dissertation, I will be looking at topics which seem to offer something interesting, even if cultural factors today often obscure their relevance. I discuss Maximus's use of the patristic distinction between 'reason' and spiritual 'intellect' as providing an interesting alternative to 'cognitive faculties.' My approach is meant to be distinctive both by reference to Greek Fathers and by studying artificial intelligence in light of the occult foundations of modern science, an important datum omitted in the broader scientific movement's self-presentation. The occult serves as a bridge easing the transition between Maximus Confessor's worldview and that of artificial intelligence. The broader goal is to make three suggestions: first, that artificial intelligence provides an experimental test of scientific materialism's picture of the human mind; second, that the outcome of the experiment suggests we might reconsider scientific materialism's I-It relationship to the world; and third, that figures like Maximus Confessor, working within an I-Thou relationship, offer more wisdom to us today than is sometimes assumed. I do not attempt to compare Maximus Confessor's Orthodoxy with other religious traditions, however I do suggest that Orthodoxy has relevant insights into personhood which the artificial intelligence community still lacks.

Introduction

Some decades ago, one could imagine a science fiction writer asking, 'What would happen if billions of dollars, dedicated laboratories with some of the world's most advanced equipment, indeed an important academic discipline with decades of work from some of the world's most brilliant minds—what if all of these were poured into an attempt to make an artificial mind based on an understanding of personhood that came out of a framework of false assumptions?' We could wince at the waste, or wonder that after all the failures the researchers still had faith in their project. And yet exactly this philosophical experiment has been carried out, in full, and has been expanded. This philosophical experiment is the artificial intelligence movement.

What relevance does AI have to theology? Artificial intelligence assumes a particular anthropology, and failures by artificial intelligence may reflect something of interest to theological anthropology. It appears that the artificial intelligence project has failed in a substantial and characteristic way, and furthermore that it has failed as if its assumptions were false—in a way that makes sense given some form of Christian theological anthropology. I will therefore be using the failure of artificial intelligence as a point of departure for the study of theological anthropology. Beyond a negative critique, I will be exploring a positive alternative. The structure of this dissertation will open with critiques, then trace historical development from an interesting alternative to the present problematic state, and then explore that older alternative. I will thus move in the opposite of the usual direction.

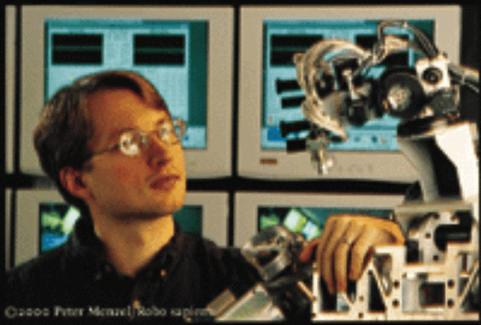

For the purposes of this dissertation, artificial intelligence (AI) denotes the endeavour to create computer software that will be humanly intelligent, and cognitive science the interdisciplinary field which seeks to understand the mind on computational terms so it can be re-implemented on a computer. Artificial intelligence is more focused on programming, whilst cognitive science includes other disciplines such as philosophy of mind, cognitive psychology, and linguistics. Strong AI is the classical approach which has generated chess players and theorem provers, and tries to create a disembodied mind. Other areas of artificial intelligence include the connectionist school, which works with neural nets,[1] and embodied AI, which tries to take our mind's embodiment seriously. The picture on the cover[2] is from an embodied AI website and is interesting for reasons which I will discuss below under the heading of 'Artificial Intelligence.'

Fraser Watts (2002) and John Puddefoot (1996) offer similar and straightforward pictures of AI. I will depart from them in being less optimistic about the present state of AI, and more willing to find something lurking beneath appearances. I owe my brief remarks about AI and its eschatology, under the heading of 'Artificial Intelligence' below, to a line of Watts' argument.[3]

Other critics[4] argue that artificial intelligence neglects the body as mere packaging for the mind, pointing out ways in which our intelligence is embodied. They share many of the basic assumptions of artificial intelligence but understand our minds as biologically emergent and therefore tied to the body.

There are two basic points I accept in their critiques:

First, they argue that our intelligence is an embodied intelligence, often with specific arguments that are worth attention.

Second, they often capture a quality, or flavour, to thought that beautifully illustrates what sort of thing human thought might be besides digital symbol manipulation on biological hardware.

There are two basic points where I will be departing from their line of argument:

First, they think outside the box, but may not go far enough. They are playing on the opposite team to cognitive science researchers, but they are playing the same game, by the same rules. The disagreement between proponents and critics is not whether mind may be explained in purely materialist terms, but only whether that assumption entails that minds can be re-implemented on computers.

Second, they see the mind's ties to the body, but not to the spirit, which means that they miss out on half of a spectrum of interesting critiques. I will seek to explore what, in particular, some of the other half of the spectrum might look like. As their critiques explore what it might mean to say that the mind is embodied, the discussion of reason and intellect under the heading 'Intellect and Reason' below may give some sense of what it might mean to say that the mind is spiritual. In particular, the conception of the intellects offers an interesting base characterisation of human thought that competes with cognitive faculties. Rather than saying that the critics offer false critiques, I suggest that they are too narrow and miss important arguments that are worth exploring.

I will explore failures of artificial intelligence in connection with the Greek Fathers. More specifically, I will look at the seventh century Maximus Confessor's Mystagogia. I will investigate the occult as a conduit between the (quasi-Patristic) medieval West and the West today. The use of Orthodox sources could be a particularly helpful light, and one that is not explored elsewhere. Artificial intelligence seems to fail along lines predictable to the patristic understanding of a spirit-soul-body unity, essentially connected with God and other creatures. The discussion becomes more interesting when one looks at the implications of the patristic distinction between 'reason' and the spiritual 'intellect.' I suggest that connections with the Orthodox doctrine of divinisation may make an interesting a direction for future enquiry. I will only make a two-way comparison between Orthodox theological anthropology and one particular quasi-theological anthropology. This dissertation is in particular not an attempt to compare Orthodoxy with other religious traditions.

One wag said that the best book on computer programming for the layperson was Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, but that's just because the best book on anything for the layperson was Alice's Adventures in Wonderland. One lesson learned by a beginning scholar is that many things that 'everybody knows' are mistaken or half-truths, as 'everybody knows' the truth about Galileo, the Crusades, the Spanish Inquisition, and other select historical topics which we learn about by rumour. There are some things we will have trouble understanding unless we can question what 'everybody knows.' This dissertation will be challenging certain things that 'everybody knows,' such as that we're making progress towards achieving artificial intelligence, that seventh century theology belongs in a separate mental compartment from AI, or that science is a different kind of thing from magic. The result is bound to resemble a tour of Wonderland, not because I am pursuing strangeness for its own sake, but because my attempt to understand artificial intelligence has taken me to strange places. Renaissance and early modern magic is a place artificial intelligence has been, and patristic theology represents what we had to leave to get to artificial intelligence.

The artificial intelligence project as we know it has existed for perhaps half a century, but its roots reach much further back. This picture attests to something that has been a human desire for much longer than we've had digital computers. In exploring the roots of artificial intelligence, there may be reason to look at a topic that may seem strange to mention in connection with science: the Renaissance and early modern occult enterprise.

Why bring the occult into a discussion of artificial intelligence? It doesn't make sense if you accept science's own self-portrayal and look at the past through its eyes. Yet this shows bias and insensitivity to another culture's inner logic, almost a cultural imperialism—not between two cultures today but between the present and the past. A part of what I will be trying to do in this thesis is look at things that have genuine relevance to this question, but whose relevance is obscured by cultural factors today. Our sense of a deep divide between science and magic is more cultural prejudice than considered historical judgment. We judge by the concept of scientific progress, and treating prior cultures' endeavours as more or less successful attempts to establish a scientific enterprise properly measured by our terms.

We miss how the occult turn taken by some of Western culture in the Renaissance and early modern period established lines of development that remain foundational to science today. Many chasms exist between the mediaeval perspective and our own, and there is good reason to place the decisive break between the mediaeval way of life and the Renaissance/early modern occult development, not placing mediaeval times and magic together with an exceptionalism for our science. I suggest that our main differences with the occult project are disagreements as to means, not ends—and that distinguishes the post-mediaeval West from the mediaevals. If so, there is a kinship between the occult project and our own time: we provide a variant answer to the same question as the Renaissance magus, whilst patristic and mediaeval Christians were exploring another question altogether. The occult vision has fragmented, with its dominion over the natural world becoming scientific technology, its vision for a better world becoming political ideology, and its spiritual practices becoming a private fantasy.

One way to look at historical data in a way that shows the kind of sensitivity I'm interested in, is explored by Mary Midgley in Science as Salvation (1992); she doesn't dwell on the occult as such, but she perceptively argues that science is far more continuous with religion than its self-understanding would suggest. Her approach pays a certain kind of attention to things which science leads us to ignore. She looks at ways science is doing far more than falsifying hypotheses, and in so doing observes some things which are important. I hope to develop a similar argument in a different direction, arguing that science is far more continuous with the occult than its self-understanding would suggest. This thesis is intended neither to be a correction nor a refinement of her position, but development of a parallel line of enquiry.

It is as if a great island, called Magic, began to drift away from the cultural mainland. It had plans for what the mainland should be converted into, but had no wish to be associated with the mainland. As time passed, the island fragmented into smaller islands, and on all of these new islands the features hardened and became more sharply defined. One of the islands is named Ideology. The one we are interested in is Science, which is not interchangeable with the original Magic, but is even less independent: in some ways Science differs from Magic by being more like Magic than Magic itself. Science is further from the mainland than Magic was, even if its influence on the mainland is if anything greater than what Magic once held. I am interested in a scientific endeavour, and in particular a basic relationship behind scientific enquiry, which are to a substantial degree continuous with a magical endeavour and a basic relationship behind magic. These are foundationally important, and even if it is not yet clear what they may mean, I will try to substantiate these as the thesis develops. I propose the idea of Magic breaking off from a societal mainland, and sharpening and hardening into Science, as more helpful than the idea of science and magic as opposites.

There is in fact historical precedent for such a phenomenon. I suggest that a parallel with Eucharistic doctrine might illuminate the interrelationship between Orthodoxy, Renaissance and early modern magic, and science (including artificial intelligence). When Aquinas made the Christian-Aristotelian synthesis, he changed the doctrine of the Eucharist. The Eucharist had previously been understood on Orthodox terms that used a Platonic conception of bread and wine participating in the body and blood of Christ, so that bread remained bread whilst becoming the body of Christ. One substance had two natures. Aristotelian philosophy had little room for one substance which had two natures, so one thing cannot simultaneously be bread and the body of Christ. When Aquinas subsumed real presence doctrine under an Aristotelian framework, he managed a delicate balancing act, in which bread ceased to be bread when it became the body of Christ, and it was a miracle that the accidents of bread held together after the substance had changed. I suggest that when Zwingli expunged real presence doctrine completely, he was not abolishing the Aristotelian impulse, but carrying it to its proper end. In like fashion, the scientific movement is not a repudiation of the magical impulse, but a development of it according to its own inner logic. It expunges the supernatural as Zwingli expunged the real presence, because that is where one gravitates once the journey has begun. What Aquinas and the Renaissance magus had was composed of things that did not fit together. As I will explore below under the heading 'Renaissance and Early Modern Magic,' the Renaissance magus ceased relating to society as to one's mother and began treating it as raw material; this foundational change to a depersonalised relationship would later secularise the occult and transform it into science. The parallel between medieval Christianity/magic/science and Orthodoxy/Aquinas/Zwingli seems to be fertile: real presence doctrine can be placed under an Aristotelian framework, and a sense of the supernatural can be held by someone who is stepping out of a personal kind of relationship, but in both cases it doesn't sit well, and after two or so centuries people finished the job by subtracting the supernatural.

Without discussing the principles in Thomas Dixon's 1999 delineation of theology, anti-theology, and atheology that can be un-theological or quasi-theological, regarding when one is justified in claiming that theology is present, I adopt the following rule:

A claim is considered quasi-theological if it can conflict with theological claims.

Given this rule, patristic theology, Renaissance and early modern magic (hereafter 'magic' or 'the occult'), and artificial intelligence claims are all considered to be theological or quasi-theological.

I will not properly trace an historical development so much as show the distinctions between archetypal scientific, occult, and Orthodox worldviews as seen at different times, and briefly discuss their relationships with some historical remarks. Not only are there surprisingly persistent tendencies, but Lee repeats Weber's suggestion that there is real value to understand ideal types.[5]

I will be attempting to bring together pieces of a puzzle—pieces scattered across disciplines and across centuries, often hidden by today's cultural assumptions about what is and is not connected—to show their interconnections and the picture that emerges from their fit. I will be looking at features including intentionality,[6] teleology,[7] cognitive faculties,[8] the spiritual intellect,[9] cosmology, and a strange figure who wields a magic sword with which to slice through society's Gordian knots. Why? In a word, all of this connected. Cosmology is relevant if there is a cosmological error behind artificial intelligence. There are both an organic connection and a distinction between teleology and intentionality, and the shift from teleology to intentionality is an important shift; when one shifts from teleology to intentionality one becomes partly blind to what the artificial intelligence picture is missing. Someone brought up on cognitive faculties may have trouble answering, 'How else could it be?'; the patristic understanding of the spiritual intellect gives a very interesting answer, and offers a completely different way to understand thought. And the figure with the magic sword? I'll let this figure remain mysterious for the moment, but I'll hint that without that metaphorical magic sword we would never have a literal artificial intelligence project. I do not believe I am forging new connections among these things, so much as uncovering something that was already there, overlooked but worth investigating.

This is an attempt to connect some very diverse sources, even if the different sections are meant primarily as philosophy of religion. This brings problems of coherence and disciplinary consistency, but the greater risk is tied to the possibility of greater reward. It will take more work to show connections than in a more externally focused enquiry, but if I can give a believable case for those interconnections, this will ipso facto be a more interesting enquiry.

All translations from French, German, Latin, and Greek are my own.

Artificial Intelligence

Artificial intelligence is not just one scientific project among others. It is a cultural manifestation of a timeless dream. It does not represent the repudiation of the occult impulse, but letting that impulse work out according to its own inner logic. Artificial intelligence is connected with a transhumanist vision for the future[10] which tries to create a science-fiction-like future of an engineered society of superior beings.[11] This artificial intelligence vision for the future is similar to the occult visions for the future we will see below. Very few members of the artificial intelligence movement embrace the full vision—but I may suggeste that its spectre is rarely absent, and that that spectre shows itself by a perennial sense of, 'We're making real breakthroughs today, and full AI is just around the corner.' Both those who embrace the fuller enthusiasm and those who are more modestly excited by current project have a hope that we are making progress towards creating something fundamentally new under the sun, of bequeathing humanity with something that has never before been available, machines that genuinely think. Indeed, this kind of hope is one of magic's most salient features. The exact content and features vary, but the sometimes heady excitement and the hope to bestow something powerful and new mark a significant point contact between the artificial intelligence and the magic that enshrouded science's birth.

There is something timeless and archetypal about the desire to create humans through artifice instead of procreation. Jewish legend tells of a rabbi who used the Kaballah to create a clay golem to defend a city against anti-semites in 1581.[12] Frankenstein has so marked the popular imagination that genetically modified foods are referred to as 'Frankenfoods,' and there are many (fictional) stories of scientists creating androids who rebel against and possibly destroy their creators. Robots who have artificial bodies but think and act enough like humans never to cause culture shock are a staple of science fiction. [13] There is a timeless and archetypal desire to create humans by artifice rather than procreation. Indeed, this desire has more than a little occult resonance.

We should draw a distinction between what may be called 'pretentious AI' and 'un-pretentious AI.' The artificial intelligence project has managed technical feats that are sometimes staggering, and from a computer scientist's perspective, the state of computer science is richer and more mature than if there had been no artificial intelligence project. Without making any general claim that artificial intelligence achieves nothing or achieves nothing significant, I will explore a more specific and weaker claim that artificial intelligence does not and cannot duplicate human intelligence.

A paradigm example of un-pretentious AI is the United States Postal Service handwriting recognition system. It succeeds in reading the addresses on 85% of postal items, and the USPS annual report is justifiably proud of this achievement.[14] However, there is nothing mythic claimed for it: the USPS does not claim a major breakthrough in emulating human thought, nor does it give people the impression that artificial mail carriers are just around the corner. The handwriting recognition system is a tool—admittedly, quite an impressive tool—but it is nothing more than a tool, and no one pretends it is anything more than a tool.

For a paradigm example of pretentious AI, I will look at something different. The robot Cog represents equally impressive feats in artificial hand-eye coordination and motor control, but its creators claim something deeper, something archetypal and mythic:

Fig. 2: Cog, portrayed as Robo sapiens[15]

The scholar places his hand on the robots' shoulder as if they had a longstanding friendship. At almost every semiotic level, this picture constitutes an implicit claim that the researcher has a deep friendship with what must be a deep being. The unfortunately blurred caption reads, '©2000 Peter Menzel / Robo sapiens.' On the Cog main website area, every picture with Cog and a person theatrically shows the person treating the robot as quite lifelike—giving the impression that the robot must be essentially human.

But how close is Cog to being human? Watts writes,

The weakness of Cog at present seems to be that it cannot actually do very much. Even its insect-like computer forebears do not seem to have had the intelligence of insects, and Cog is clearly nowhere near having human intelligence.[16]

The somewhat light-hearted frequently-asked-questions list acknowledges that the robot 'has no idea what it did two minutes ago,' answers 'Can Cog pass the Turing test?' by saying, 'No... but neither could an infant,' and interestingly answers 'Is Cog conscious?' by saying, 'We try to avoid using the c-word in our lab. For the record, no. Off the record, we have no idea what that question even means. And still, no.' The response to a very basic question is ambiguous, but it seems to joke that 'consciousness' is obscene language, and gives the impression that this is not an appropriate question to ask: a mature adult, when evaluating our AI, does not childishly frame the question in terms of consciousness. Apparently, we should accept the optimistic impression of Cog, whilst recognising that it's not fair to the robot to ask about features of human personhood that the robot can't exhibit. This smells of begging the question.

Un-pretentious AI makes an impressive technical achievement, but recognises and acknowledges that they've created a tool and not something virtually human. Pretentious AI can make equally impressive technical achievements, and it recognises that what it's created is not equivalent to human, but it does not acknowledge this. The answer to 'Is Cog conscious?' is a refusal to acknowledge something the researchers have to recognise: that Cog has no analogue to human consciousness. Is it a light-hearted way of making a serious claim of strong agnosticism about Cog's consciousness? It doesn't read much like a mature statement that 'We could never know if Cog were conscious.' The researcher in Figure 2 wrote an abstract on how to give robots a theory of other minds[17], which reads more like psychology than computer science.