First Things, in a column by Fr. Richard John Neuhaus, muses,

The clock is ticking, and many in the Archdiocese of Milwaukee are counting the days, the hours, and even the minutes before Archbishop Rembert Weakland has to submit his resignation at twelve noon on his seventy-fifth birthday. I am told that the champagne bottles will be popped at 12:01 p.m. upon receiving the fax from Rome that the resignation is accepted. Truth to tell, I’ve always had something of a soft spot for the Archbishop. He’s liberally daffy but more amusingly candid than most of that persuasion. Of course he has a very high opinion of himself, but he’s never tried to hide it. I particularly liked his public statement that he would have made a great Bishop of Salzburg in the time of Mozart but ended up as Bishop of Milwaukee in the time of rock and roll. There’s something perversely refreshing about a bishop who doesn’t mind saying that he’s too good for the people he’s called to serve.

If I had been meant to live in Salzburg at Mozart's time, God would have done that. If I had been meant to live in the Middle Ages, in the desire that underpinned my second novel, God would have done that. And if I if I had been made to live in the age of many Church Fathers, God would have done that too. As it is, God's providence has placed me here and now... and God may make of me a Church Father anyway, without a time machine. To nostalgic Romans, it may be a sadness that the door to the Middle Ages is closed, but to Orthodox living at the corner of east and now, the door to being patristic remains ever open, and I may die (or be subtilized by the returning Christ) a Church Father anyway. As things are, God has given me a whole lot of being in the right place in the right time, and put me in the days of... myself! I got onto the web by accident (or rather by providence that I did not see as significant) and I have multiple major websites and a big bookshelf on Amazon.

As I write, incidentally, the majority of U.S. flags I've seen are black and white with a strip of color, the old "Don't tread on me" rattlesnake flag is seen not infrequently, and when I popped in to LinkedIn turned up a friend reflecting on a news item that grandmas are buying shotguns. I did not expect that, but I am not in the least surprised.

And one other thing: I can't meaningfully prep apart from measures I have taken that have been unfruitful. I am on maintenance medications, and if I stop taking them, I'll die within days. And as I write I seem to have COVID.

And in all this, I am grateful. St. John Chrysostom's final words were, "Glory be to God for all things!" and I echo them. I have food, shelter, clothing, medicine, and really quite a lot of things that I do not need and I am not entitled to. I only need to be faithful today with what I have today. God will bring tomorrow, and not knowing what tomorrow may bring i s much less important if you know Who will bring tomorrow.

And my death is, basically, non-negotiable. God, in his great mercy, does not let us know ahead of time when we die, because we would put off repentance and be incorrigible sinners in the hour of death. A few saints know ahead when they will die. They are so secure spiritually that they will not be less faithful for knowing. For the rest of us, it is mercy that we do not know. I could, possibly, die within days. I could for that matter die sooner: when I got my first COVID injection, a blood clot formed in my leg and dislodged to make trouble in my lungs, and the doctor said I was lucky I got to the hospital when I did, because it could have killed me. I think COVID injections are the greatest breakthrough in human health since DDT, but I digress. I could die an old man, like my grandfather who lived to be 95. I could live to see the returning Christ. And which of these, or other possibilities, hold, is not my concern. Each day has enough trouble of its own—and I have found solving a life's problems on a day's resources to be an entirely preventable ticket to despair.

Some people think that this life is only a preparatory life and is therefore unimportant St. Nikolai, in Prayers by the Lake, talked (I forget exactly where) about how birth and death are only an inch apart, and the ticker tape goes on forever.

This makes what we choose in this life incredibly important. We can only "save for retirement" between birth and death. We can only repent between birth and death. After death, improving the lot we have eternally chosen in this life will be impossible. I wish to live in repentance for the rest of my life, but I have not gotten to monasticism yet, but if death cuts short my attempts, that matters less than you might think. God treats an active intent as if the person had done what is intended; I do not see I can rightly stop seeking monastic repentance, but if I am faithful and fail, I am in the same position as martyrs said to be "baptized in their own blood" because they were martyred before they could even reach baptism.

And, to borrow from a childhood favorite, A Wind in the Door (my esteem is much less for it now), the heroine "felt as though fingers were gentle fingers pushing her down," I sought to stay when I visited Mount Athos and was told that the conditions for being made a saint are in America, and implicitly reminded that monastic "white martyrdom" is an artificial surrogate to the "red martyrdom" of the Church in a hostile world.

I would like to quote a unicorn in C.S. Lewis, The Last Battle, though I'm not sure it applies to our world:

He said that the Sons and Daughters of Adam and Eve were brought out of their own strange world only at times Narnia was upset, but she mustn't think that things were always like that. In between their visits there were hundreds and thousands of years when peaceful king followed peaceful king till you could hardly remember their names or count their numbers, and there was really hardly anything to put in the History Books.

As to the question of why God did not create Narnia and bring me to it, I reply that every excellence is incomparably excelled in what "eye has not seen, ear has not heard, nor any heart imagined what God has prepared for those who love him." I can't get to a real Narnia, but I'm trying to get to a real "better than Narnia," a "better than Narnia that begins on earth, as I discuss in A Pilgrimage from Narnia:

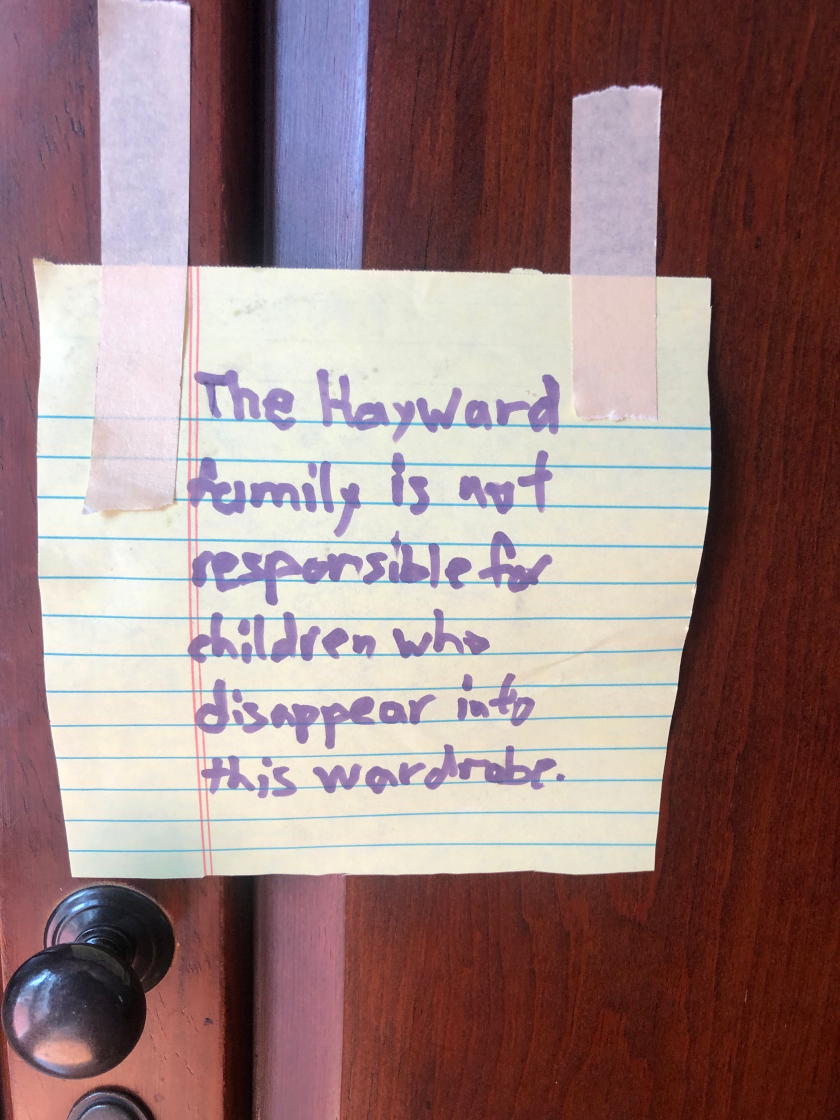

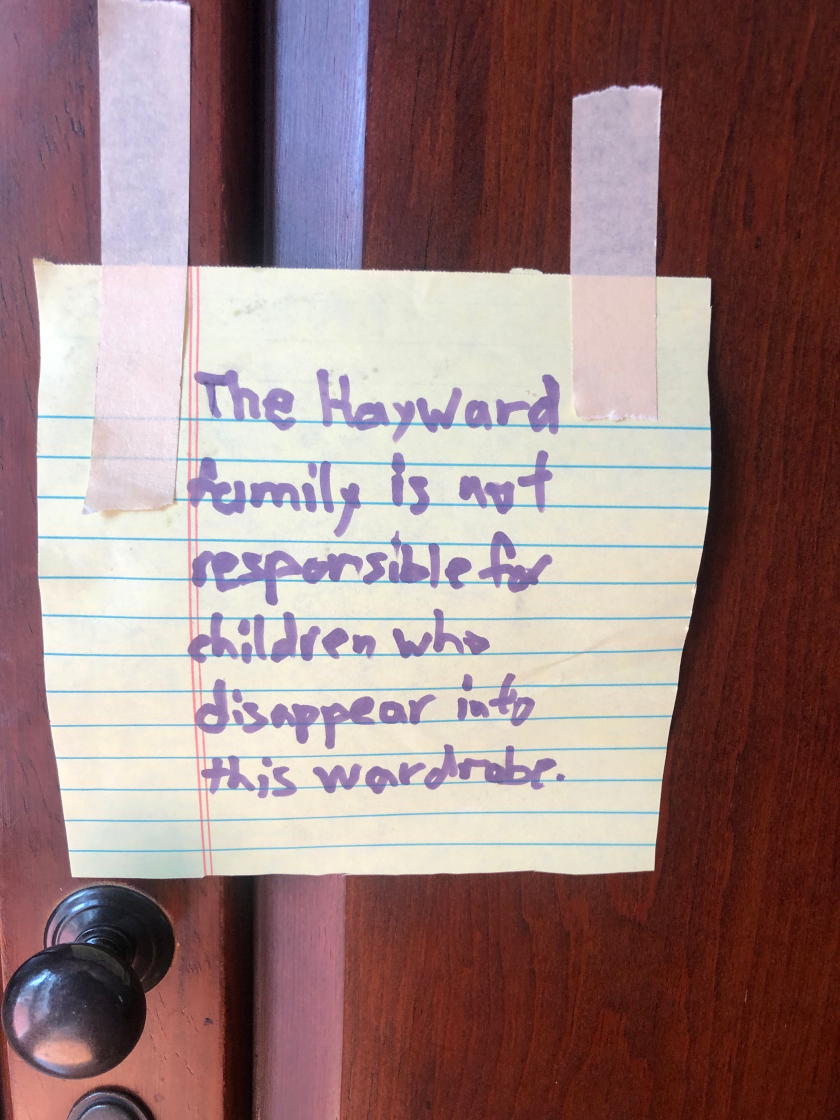

A Pilgrimage from Narnia

Wardrobe of fur coats and fir trees:

Sword and armor, castle and throne,

Talking beast and Cair Paravel:

From there began a journey,

From thence began a trek,

Further up and further in!The mystic kiss of the Holy Mysteries,

A many-hued spectrum of saints,

Where the holiness of the One God unfurls,

Holy icons and holy relics:

Tales of magic reach for such things and miss,

Sincerely erecting an altar, "To an unknown god,"

Enchantment but the shadow whilst these are realities:

Whilst to us is bidden enjoy Reality Himself.

Further up and further in!A journey of the heart, barely begun,

Anointed with chrism, like as prophet, priest, king,

A slow road of pain and loss,

Giving up straw to receive gold:

Further up and further in!Lord Jesus Christ, have mercy on me, a sinner,

Silence without, building silence within:

The prayer of the mind in the heart,

Prayer without mind's images and eye before holy icons,

A simple Way, a life's work of simplicity,

Further up and further in!A camel may pass through the eye of a needle,

Only by shedding every possession and kneeling humbly,

Book-learning and technological power as well as possessions,

Prestige and things that are yours— Even all that goes without saying:

To grow in this world one becomes more and more;

To grow in the Way one becomes less and less:

Further up and further in!God and the Son of God became Man and the Son of Man,

That men and the sons of men might become gods and the sons of God:

The chief end of mankind,

Is to glorify God and become him forever.

The mysticism in the ordinary,

Not some faroff exotic place,

But here and now,

Living where God has placed us,

Lifting where we are up into Heaven:

Paradise is wherever holy men are found.

Escape is not possible:

Yet escape is not needed,

But our active engagement with the here and now,

And in this here and now we move,

Further up and further in!We are summoned to war against dragons,

Sins, passions, demons:

Unseen warfare beyond that of fantasy:

For the combat of knights and armor is but a shadow:

Even this world is a shadow,

Compared to the eternal spoils of the victor in warfare unseen,

Compared to the eternal spoils of the man whose heart is purified,

Compared to the eternal spoils of the one who rejects activism:

Fighting real dragons in right order,

Slaying the dragons in his own heart,

And not chasing (real or imagined) snakelets in the world around:

Starting to remove the log from his own eye,

And not starting by removing the speck from his brother's eye:

Further up and further in!Spake a man who suffered sorely:

For I reckon that the sufferings of this present time,

Are not worthy to be compared with the glory which shall be revealed in us, and:

Know ye not that we shall judge angels?

For the way of humility and tribulation we are beckoned to walk,

Is the path of greatest glory.

We do not live in the best of all possible worlds,

But we have the best of all possible Gods,

And live in a world ruled by the him,

And the most painful of his commands,

Are the very means to greatest glory,

Exercise to the utmost is a preparation,

To strengthen us for an Olympic gold medal,

An instant of earthly apprenticeship,

To a life of Heaven that already begins on earth:

He saved others, himself he cannot save,

Remains no longer a taunt filled with blasphemy:

But a definition of the Kingdom of God,

Turned to gold,

And God sees his sons as more precious than gold:

Beauty is forged in the eye of the Beholder:

Further up and further in!When I became a man, I put away childish things:

Married or monastic, I must grow out of self-serving life:

For if I have self-serving life in me,

What room is there for the divine life?

If I hold straw with a death grip,

How will God give me living gold?

Further up and further in!Verily, verily, I say to thee,

When thou wast young, thou girdedst thyself,

And walkedst whither thou wouldest:

But when thou shalt be old,

Thou shalt stretch forth thy hands, and another shall gird thee,

And carry thee whither thou wouldest not.

This is victory:

Further up and further in!

And for our world, I would quote C.S. Lewis in saying that "humanity has always been on a precipice." Such study as I have had of Byzantine history leads me not to wonder that Constantinople fell, but that over a millennium after Constantine, after many times the Empire should have resolved, it took modern cannons to break through Constantinople's walls and subdue the great city. "Humanity has always been on a precipice"--and it seems to be increasingly more of a precipice.

It is believed by some Orthodox that Hinduism has room for the demonic and OrthoChristian.com describes Orthodox mission in India as “Perpetual Embers,” but do not speak ill to a Hindu of Krishna and the milk-maids. However, it is not provocative to call Kali demonic: a goddess of death who wears a necklace of skulls and bestows madness as her special blessing. Or at least I don’t see why it need offend a Hindu.

I have what I would call an "unintendedly kept loan" in that I was loaned a copy of the Bhagavad-Gita ("Song of God") by an Indian woman, and then lost all contact and don't see how to return it. Nor was the loan small; the Bhagavad-Gita was accompanied by commentary, as is Hindu tradition to unpack their greatest classic, in a beautiful two-volume boxed set. And the front matter talked about our being in the "Kali-yuga," or age of Kali. I don't know or understand what exactly a Hindu would mean by the Kali-yuga, but I can take a guess. And I have had some contact with the movement called "Traditionalists," which find certain underlying themes in many world religions that are threatened in the modern way of life and are sympathetic to Hindus who would see a Kali-yuga:

There is a singularity which has developed over past centuries, was present in decisive breaks made in the scientific revolution that paved the way to hard science as we know it, and has been unfolding and accelerating, and now crassly has vomited TV's and cellphones on Africa, the poorest continent. One obvious question is, "Do you mean the Book of Revelation?" and my answer is an emphatic "Yes... and No..." There are certain things which I believe we have been told will pass as Revelation is fulfilled. These include great tribulation, the coming of the Antichrist, and the return of Christ in glory to judge the living and the dead, and the glorious resurrection. But trying to pin down Biblical prophecy down in detail is essentially an attempt to get a crystal clear view into deep waters that are impregnably and unfathomably murky. Don't, at least not before the prophecies have been fulfilled.

However, while I have extreme suspicion for detailed point-for-point pinpointing the events in Revelation, I think it is a much more possible and profitable measure to study the singularity we are in as a singularity, a point I explore with some video in Revelation and Our Singularity.

A student of World War II may be able to pinpoint a linchpin in German manufacturing. There was a single point of failure in a ball bearing factory. If that factory had been taken out, it would all but destroyed Nazi Germany's capability to produce cars, trucks, tanks, and airplanes. Now let me ask: where is the linchpin in our technological society? Trick question! There are so many that no one knows how many there are. One of the most Luddite statements I've read is from a computer programmer: "If builders built buildings the way computer programmers write programs, the first woodpecker that came along would destroy civilization."

At Honey Rock, there was a delightful place called "the Web" that used World War II cargo netting to make a great amusement for kids. It, after several decades, fell beyond safe use, and the camp's people tried hard to find replacements. There were none to be found, came the conclusion from their research. Furthermore, it is now a respectable number of decades since technological museum curators have computer media that they believe to likely be intact but which they have no idea how to interpret. Cryptanalysis can break all sorts of very well-engineered codes. However, storage media produced with neither the desire nor attempt towards secrecy cannot straightforwardly read media that was intended to be straightforward to read.

To put things in miniature, like almost any at least half-serious website I have switched from sending unencrypted HTTP to confidential HTTPS. This was a right decision, I believe. However, to do that I need to get a stream of certificates, and if someone by any means shut down my ability to obtain certificates, my website would practically be dead in the water. Search engines would now be linking to security error pages; even bookmarks wouldn't work. I might be able to get the word out that my website was served via HTTP, if I wasn't blocked from social media by that time, but my use of the recommended practice of serving webpages confidentially via HTTPS introduces one more single point of failure. (That's why I'm revamping and roughly doubling my "Complete Works" collections in paperback. Amazon believes it has a total right to delete anything from a Kindle any time.) We are going from fragile to more and more and more fragile, to an effect like that in The Damned Backswing.

In a homily a few weeks back, my priest said,

Let us go to the Egyptian desert, and overhear a conversation taking place between a group of monks led by Abba Iscariot. This took place in the third century and the conversation went like this.

Abba Iscariot was asked, "What have we done in our life?"

The Abba replied, "We have done half of what our fathers did."

When asked, "What will the ones who come after us do?"

The Abba replied, "They are doing the half of what we are doing now."

And to the question, "What will the Christians of the last days do?"

He replied, "They will not be able to do any spiritual exploits, but those who keep the faith, they will be glorified more than our fathers who raised the dead."

We live in an exciting time.

My spiritual director said, "We think we are not on Plan A any more, not on Plan B, not on Plan C, and so on down the alphabet, but God is always on Plan A.

If you wonder how that could possibly be, I invite you to read God the Spiritual Father.

Though I'd rather you just enjoy this page on the web and share it with your friends than actually purchase this.

(Sweatshops and all that...)

O King of Kings,

O Lord of Lords,

O God of Gods,

Who hast created me,

Why do I wish to be a king?

And why am I not satisfied,

That the Risen Christ,

Victor, King,

Hast taken our human nature,

And hast enthroned our royal race,

On His own Heavenly Throne.

If it is honour that I seek,

What more is there for me to ask,

If you admit me to your courts of worship,

And I receive the Holy Mysteries?

If it status,

And Thou receivedst me as faithful,

Anointed,

Prophet, priest, and king,

What there is more for me to ask?

Or is my disease different,

Not from any lack of honours paid,

But something cured by humility,

Not sated by the adding to the sum of my possessions,

But sated by subtracting from the sum of my desires?

And the particulars of my case:

What of them?

My PhD program was shut down,

At ill-famed Fordham University

("We have no initials!"),

And it was not mere politeness,

When the head of International Christian Mensa said,

"Your job is not to write the books that PhD's write.

Your job is to write the books that PhD's read."

And I was missing something,

When I wished some kind institution,

Would grant me some honorary degree.

A psychologist pulled me aside and asked,

"How many profoundly gifted people do you think there are at Harvard?"

Then another question and then another,

Until he drove a point:

"The average Harvard PhD has never met

Someone as talented as you."

Did I mention that as a child,

I wished for an IQ of 400?

There are a great many stupid things I've wished.

What more do I wish to ask,

Now that I am retired on disability,

With a roof over my head,

And a little more income?

Is Heaven given to me less?

Is Christ? Is the Holy Spirit?

Should I ask my dear Archbishop PETER for coronation,

Or just follow an ad for "Real English titles of nobility?"

Even if His Eminence were to give me,

One of the bare titles that he doesn't like,

Would I be the more the King of my website?

I have a roof over my head;

A wrecked career is not the worst option;

And the resources of Heaven remain open;

Even St. Michael, whose afterfeast falls as I write.

I pass through life like a vagabond,

Collecting letters after my name,

From the Sorbonne, UIUC, and Cambridge,

Possibly it is a blow of mercy that my studies at Fordham got no further,

And still I write:

And still I write.

Before the advent in force of body wave feminism,

I remember reading of women,

That the ones at peace with their figures,

Are not those of greatest external beauty,

And to be a model is to be still more insecure.

Trying to make peace with your figure,

By wearing yourself out through diet and exercise,

Is barking up the wrong fire hydrant,

Almost as foolish as me chasing honour.

People who win big,

Spend big,

And many lottery winners go bankrupt.

I would love to have a BMW,

But if a Ford is my biggest unmet wish,

I am doing well.

Why do I covet more,

When you give me freely,

More than I could imagine to ever ask?

[With apologies to St. Seraphim, and I really hope my adaptation doesn't come across as comparing myself to a great saint I am deeply indebted to!]

To Your Brilliance, and you know who you are:

On the topic of worry, Your Brilliance said that I was a monk and therefore not subject to worry, but you, not being a monk, have worries. And I, poor not-even-a-novice Christos, wish to open your eyes to something. I, poor Christos, have nothing that is not an open door for you.

Where to begin?

One start might begin with commercials to stimulate covetousness back in 1993:

Some of the technologies in the "YOU WILL" commercials are already obsolete; we don't need to get tickets from an ATM because we can do that with a phone in our pockets, and we don't need to carry our medical records in our pockets because the electronic storage of records obviates the need to carry a physical device so doctors can have your records.

But in retrospect, the following "anti-commercial" could be added:

Have you ever drained yourself by compulsively checking your phone easily a hundred times a day?

Have you ever had several Big Brothers know your every every step, every heartbeat?

Have you ever had every keystroke you’ve ever typed be recorded and available to use against you for all your remaining life?

Have you ever met people from the last generation that remembers what life was like before the world went digital?

and AT&T ain’t the only company that will bring it to you!

No technology is permanently exotic. It may be the case that Jakob Nielsen said, "In the future, we'll all be Harry Potter," meaning we will all have gadgets that do super things. It did not, of course, mean that we will be playing Quidditch—a dated remark, given that we now have flying motorcycles:

It might be deadly difficult to use them to try and play Quidditch, or perhaps some Internet of Things technology could make such Quidditch playing no more dangerous than in J.K. Rowling's imagination, but that important safety caveat does not change the fact that we can do things Nielsen didn't imagine... but still, no technology is permanently exotic, and none of these technologies really change the poverty that "Old Economy Steve" was privileged not to even need to fathom:

And the picture is false if it is assumed that "YOU WILL" is simply Old Economy Steve's vibrant economy with electronic tolling and other such things tacked on.

There was one story poor Christos thought to write, but it has some things intended at surface level that apparently are not at surface level. Hysterical Fiction: A Medievalist Jibe at Disney Princess Videos was intended to be an obvious inversion of a bad habit in fantasy and historical fiction that has at least one postmodern wearing armor. The reading experience is like what it is like for an American to travel to England, enter a shop, and be greeted with the same accent as back home. However, very few people got it, so poor not-even-a-novice Christos would rather tell of a story than tell the imagined story itself.

The story would be set in what is treated as a dark science fiction world, and presents the shock of seeing how things really are, that we have pretty much everything promised in the "YOU WILL" commercials, if perhaps not the Old Economy Steve assumptions about basic wealth.

But amidst this darkness is something important, a light that shines in many places. It has been said that Paradise is simply where the saints are, and the well-worth-reading story of Fr Arseny: Priest, Prisoner, Spiritual Father tells of a priest who carries Paradise with himself, even in a concentration camp! And the real core of the story I have wanted to tell is "Guilty as charged" for every element of dark science fiction dystopic reality, but that is really much less significant than a character of light who shines in even the deepest darkness. The Light shines in the darkness, and the darkness never gets it.

Peter Kreeft said that the chief advantage of wealth is that it does not make you happy. If you are poor, perhaps perennially struggling to make ends meet, it may be a difficult temptation to resist to think that if you had money, all your problems would go away. Being wealthy clips the wings of that illusion, and our science-fictiony present clips somewhat the wings of the illusion that life would be great if we could send a fax from the beach. Windows Mobile was advertised under the rubric of "When, why, where, and how you want to work," when it should be, "You will never be free from the shackles of your job."

I would quote the Sermon on the Mount:

“Lay not up for yourselves treasures upon earth, where moth and rust doth corrupt, and where thieves break through and steal: but lay up for yourselves treasures in Heaven, where neither moth nor rust doth corrupt, and where thieves do not break through nor steal: for where your treasure is, there will your heart be also. The light of the body is the eye: if therefore thine eye be single, thy whole body shall be full of light. But if thine eye be evil, thy whole body shall be full of darkness. If therefore the light that is in thee be darkness, how great is that darkness! No man can serve two masters: for either he will hate the one, and love the other; or else he will hold to the one, and despise the other. Ye cannot serve God and mammon.

“Therefore I say unto you, Do not worry about your life, what ye shall eat, or what ye shall drink; nor yet for your body, what ye shall put on. Is not the life more than food, and the body than garments? Behold the fowls of the air: for they sow not, neither do they reap, nor gather into barns; yet your heavenly Father feedeth them. Are ye not much better than they? Do you think you can add one single hour to your life by worrying? You might as well try to worry yourself into being a foot taller!

“And why do you worry for garments? Consider the lilies of the field, how they grow; they toil not, neither do they spin: and yet I say unto you, Even Solomon in all his glory was not arrayed like one of these. 30 Wherefore, if God so clothe the grass of the field, which to day is, and to morrow is cast into the oven, shall he not much more clothe you, O ye of little faith?

“Therefore do not worry, saying, ‘What shall we eat?’ or, ‘What shall we drink?’ or, ‘Wherewithal shall we be clothed?’ (For after all these things do the Gentiles seek:) for your heavenly Father knoweth that ye have need of all these things. But seek ye first the Kingdom of God, and His righteousness; and all these things shall be added unto you. Do not worry about the morrow: for the morrow has enough worries of its own. Sufficient unto the day is the evil thereof.

"If thine eye be single:" a reading of this verse in translations often has the word "healthy" or "sound," and those readings are true. However, in the middle of a real sandwich of teaching about storing up treasures in Heaven and earth, "single" is singularly appropriate. Its meaning is cut from the same cloth as the warning, "Ye cannot serve God and mammon." A "single" eye is one that is undivided, that does not multitask, that as an old hymn says,

Keep your eyes on Jesus,

Look full in His wonderful face,

And the things of this world will grow strangely dim,

In the light of his glory and grace.

What poor Christos has, and this is something monastic aspirants should aspire to, but not anything should be a "greater monasticism" monopoly, is not in any sense being better at planning; it may mean in fact being worse at planning. All of poor, not-even-a-novice Christos's lessons about worrying have not been being better at planning for the future; experience is that trying to solve a life's problems on a day's resources opens the door to despair. What is needed is not greater planning but greater focus on today, and allowing tomorrow to worry for itself. "Each day has enough trouble of its own" is very practical advice. Poor Christos is no better at solving all problems in a day than Your Brilliance; poor Christos is just a little bit better at letting go and trusting in Divine Providence.

That Providence orders the Dance. Blessed Augustine said that if a master sends two slaves along paths that will cross, their meeting is a coincidence from the slaves' perspective but intended by the master as planned. One thing we find in escaping the Hell of self is that that is how God opens our eyes to a broader world.

And really, refraining from worry is the outer layer where there are many layers underneath. People who delve deeper may have no plans; trusting God that if they obey God today, God will plan for them tomorrow. Identity as we understand it today is another treasure on earth we are to let go of, and digging deeper is something of an opposite of magic. I remember as the Hell of self when I had a job and an extended stay hotel room, and I was able to set up technology exactly as my poor self wanted. It might as well have been magic. G.K. Chesterton famously said, "The poet only asks to get his head into the Heavens. The logician tries to get the Heavens into his head, and it is his head that splits." Magic is an attempt to reduce things to the point that we will have more control, while dancing with the Lord of the Dance opens our hands instead of closing them. C.S. Lewis says that we want God to change our circumstances, where God wants our circumstances to control us. Right now poor less-than-a-novice Christos has been working on the Classic Orthodox Bible and trying to publish it in hardcover with larger text when it is cramped as an Amazon paperback. And I wanted to have it ready for the Sunday of Orthodoxy, but it is not appearing like it will be ready; but there may be something in publishing it the next Sunday, the Sunday of St. Gregory Palamas. All concrete hopes, with an 'S' as in 'Shit', will be disappointed. Hope proper, Hope in God, will be fulfilled.

TED talks have made a great deal out of the Stoicism that is a secret weapon in the National Handegg League, with observations like "We suffer more in imagination than in reality." And it is a blinding flash of the obvious that philosophy could make a difference to real people. But what we have here is something more than Stoicism. Stoicism's strengths are preserved in the Philokalia, and there is more. Stoicism is of some benefit, but it does not tell us to follow the Lord of the Dance. It is worth noting, and practical in benefit, but eclipsed by a living exegesis of the Sermon on the Mount:

Righteous Philaret the Merciful, son of George and Anna, was raised in piety and the fear of God. He lived during the eighth century in the village of Amneia in the Paphlagonian district of Asia Minor. His wife, Theoseba, was from a rich and illustrious family, and they had three children: a son John, and daughters Hypatia and Evanthia.

Philaret was a rich and illustrious dignitary, but he did not hoard his wealth. Knowing that many people suffered from poverty, he remembered the words of the Savior about the dread Last Judgment and about “these least ones” (Mt. 25:40); the the Apostle Paul’s reminder that we will take nothing with us from this world (1 Tim 6:7); and the assertion of King David that the righteous would not be forsaken (Ps 36/37:25). Philaret, whose name means “lover of virtue,” was famed for his love for the poor.

One day Ishmaelites [Arabs] attacked Paphlagonia, devastating the land and plundering the estate of Philaret. There remained only two oxen, a donkey, a cow with her calf, some beehives, and the house. But he also shared them with the poor. His wife reproached him for being heartless and unconcerned for his own family. Mildly, yet firmly he endured the reproaches of his wife and the jeers of his children. “I have hidden away riches and treasure,” he told his family, “so much that it would be enough for you to feed and clothe yourselves, even if you lived a hundred years without working.”

The saint’s gifts always brought good to the recipient. Whoever received anything from him found that the gift would multiply, and that person would become rich. Knowing this, a certain man came to St Philaret asking for a calf so that he could start a herd. The cow missed its calf and began to bellow. Theoseba said to her husband, “You have no pity on us, you merciless man, but don’t you feel sorry for the cow? You have separated her from her calf.” The saint praised his wife, and agreed that it was not right to separate the cow and the calf. Therefore, he called the poor man to whom he had given the calf and told him to take the cow as well.

That year there was a famine, so St Philaret took the donkey and went to borrow six bushels of wheat from a friend of his. When he returned home, a poor man asked him for a little wheat, so he told his wife to give the man a bushel. Theoseba said, “First you must give a bushel to each of us in the family, then you can give away the rest as you choose.” Philaretos then gave the man two bushels of wheat. Theoseba said sarcastically, “Give him half the load so you can share it.” The saint measured out a third bushel and gave it to the man. Then Theoseba said, “Why don’t you give him the bag, too, so he can carry it?” He gave him the bag. The exasperated wife said, “Just to spite me, why not give him all the wheat.” St Philaret did so.

Now the man was unable to lift the six bushels of wheat, so Theoseba told her husband to give him the donkey so he could carry the wheat home. Blessing his wife, Philaret gave the donkey to the man, who went home rejoicing. Theoseba and the children wept because they were hungry.

The Lord rewarded Philaret for his generosity: when the last measure of wheat was given away, a old friend sent him forty bushels. Theoseba kept most of the wheat for herself and the children, and the saint gave away his share to the poor and had nothing left. When his wife and children were eating, he would go to them and they gave him some food. Theoseba grumbled saying, “How long are you going to keep that treasure of yours hidden? Take it out so we can buy food with it.”

During this time the Byzantine empress Irene (797-802) was seeking a bride for her son, the future emperor Constantine Porphyrogenitos (780-797). Therefore, emissaries were sent throughout all the Empire to find a suitable girl, and the envoys came to Amneia.

When Philaret and Theoseba learned that these most illustrious guests were to visit their house, Philaret was very happy, but Theoseba was sad, for they did not have enough food. But Philaret told his wife to light the fire and to decorate their home. Their neighbors, knowing that imperial envoys were expected, brought everything required for a rich feast.

The envoys were impressed by the saint’s daughters and granddaughters. Seeing their beauty, their deportment, their clothing, and their admirable qualities, the envoys agreed that Philaret’ granddaughter, Maria was exactly what they were looking for. This Maria exceeded all her rivals in quality and modesty and indeed became Constantine’s wife, and the emperor rewarded Philaret.

Thus fame and riches returned to Philaret. But just as before, this holy lover of the poor generously distributed alms and provided a feast for the poor. He and his family served them at the meal. Everyone was astonished at his humility and said: “This is a man of God, a true disciple of Christ.”

He ordered a servant to take three bags and fill one with gold, one with silver, and one with copper coins. When a beggar approached, Philaret ordered his servant to bring forth one of the bags, whichever God’s providence would ordain. Then he would reach into the bag and give to each person, as much as God willed.

St Philaret refused to wear fine clothes, nor would he accept any imperial rank. He said it was enough for him to be called the grandfather of the Empress. The saint reached ninety years of age and knew his end was approaching. He went to the Rodolpheia (“The Judgment”) monastery in Constantinople. He gave some gold to the Abbess and asked her to allow him to be buried there, saying that he would depart this life in ten days.

He returned home and became ill. On the tenth day he summoned his family, he exhorted them to imitate his love for the poor if they desired salvation. Then he fell asleep in the Lord. He died in the year 792 and was buried in the Rodolpheia Judgment monastery in Constantinople.

The appearance of a miracle after his death confirmed the sainthood of Righteous Philaret. As they bore the body of the saint to the cemetery, a certain man, possessed by the devil, followed the funeral procession and tried to overturn the coffin. When they reached the grave, the devil threw the man down on the ground and went out of him. Many other miracles and healings also took place at the grave of the saint.

After the death of the righteous Philaret, his wife Theoseba worked at restoring monasteries and churches devastated during a barbarian invasion.

St. Philaret did not just refrain from worry; he played his part in the Great Dance, and God gave him a wonderful story.

As far as all these things that his wife Theoseba could not see, his trust reached the level of, really, an arrogance, the same arrogance whose hymn I wrote:

Song VIII.

A HYMN TO ARROGANCE.

The Saint opened his Golden Mouth and sang,

‘There be no war in Heaven,

Not now, at very least,

And not ere were created,

The royal race of mankind.

Put on your feet the Gospel of peace,

And pray, a-stomping down the gates of Hell.

There were war in Heaven but ever brief,

The Archangel Saint Michael,

Commander of the bodiless hosts,

Said but his name, “Michael,”

Which is, being interpreted,

“Who is like God?”

With that the rebellion were cast down from Heaven,

Sore losers one and all.

They remain to sharpen the faithful,

God useth them to train and make strength.

Shall the axe boast itself against him that heweth therewith?

Or shall the saw magnify itself against him that shaketh it?

As if the rod should shake itself against them that lift it up,

Or as if the staff should lift up itself,

As if it were no wood.

Therefore be not dismayed,

If one book of Holy Scripture state,

That the Devil incited King David to a census,

And another sayeth that God did so,

For God permitted it to happen by the Devil,

As he that heweth lifteth an axe,

And God gave to David a second opportunity,

In the holy words of Joab.

Think thou not that God and the Devil are equal,

Learnest thou enough of doctrine,

To know that God is greater than can be thought,

And hath neither equal nor opposite,

The Devil is if anything the opposite,

Of Michael, the Captain of the angels,

Though truth be told,

In the contest between Michael and the Devil,

The Devil fared him not well.

The dragon wert as a little boy,

Standing outside an Emperor’s palace,

Shooting spitwads with a peashooter,

Because that wert the greatest harm,

That he saweth how to do.

The Orthodox Church knoweth well enough,

‘The feeble audacity of the demons.’

Read thou well how the Devil crowned St. Job,

The Devil and the devils aren’t much,

Without the divine permission,

And truth be told,

Ain’t much with it either:

God alloweth temptations to strengthen;

St. Job the Much-Suffering emerged in triumph.

A novice told of an odd clatter in a courtyard,

Asked the Abbot what he should do:

“It is just the demons.

Pay it no mind,” came the answer.

Every devil is on a leash,

And the devout are immune to magic.

Thou shalt tread upon the lion and adder:

The young lion and the dragon shalt thou trample under feet.

The God of peace will soon crush Satan under your feet.

Wherefore be thou not arrogant towards men,

But be ever more arrogant towards devils and the Devil himself:

“Blow, and spit on him.”‘

The Consolation of Theology tells in part the author's worries and wishing to be in control, and learning something that is the very opposite of what we both reach for.

There was a simple "game" on Macintoshes when poor Christos was in high school, called "Global Thermonuclear War," with a "Launch" button. Press the button, and all kinds of missiles launch worldwide and destroy the earth. The lesson is articulated in words: "The only way to win the game is not to play at all." And so it is with worry.

"Do not store up treasures on earth." The further we grow into this, the more we discover we have treasures on earth to give up... and the more we give them up, the more treasures in Heaven our hands are empty enough to receive.

St. Seraphim had a remarkable dialogue with a pilgrim about the meaning of life, and he said it was one thing: the acquisition of the Holy Spirit. Good works do not reach their full stature unless they are relational, done to connect with God. And really, what greater treasure in Heaven is there to have than the Holy Spirit? The expurgation seems painful, and it is painful, but the pain does not last. Or rather it is transcended, like the saint in the story posited above transcends a dark science fiction dystopia. But there is tremendous freedom in letting go.

God wants to open us up to a larger world. Once poor Christos confessed to not being open to God, and was instead of a usual correction was advised to be mindful of the fact that God and the saints are open to us.

But to give a sudden close, poor Christos will reread St. John, A Treatise to Prove that Nothing Can Injure the Man Who Does Not Harm Himself. He needs it, and you might too.

To my parents John and Linda—

I owe you more than words can say.

Martin Seligman, a giant in the psychological community, kicked off a major TED talk by talking about how a TV station wanted a sound bite from him, and it should be one word. He said, "Good." Then they decided that as the president of the American Psychological Association he was a figure of such stature that they would let him have two words, and he said, "Not good." Finally, they decided he was of such stature that he would be allowed three words, and his three words were, "Not good enough."

What he was getting at was essentially as follows: clinical psychology had a goal which was remarkably well accomplished: the complete classification of behavioral health conditions, along with effective psychiatric treatment and psychotherapy. He didn't really underscore the magnitude and implications of this goal; apart from the fact that public figures know they at least need to act humble publicly, sometimes greatness brings real humility and he was trying to lead people to see there was more to ask for than just getting someone to feel OK, and he did not suggest that clinical psychology is the kind of tool that lets people of all kinds to thrive in every way. He called for a positive psychology to help people thrive, have fulfilling and delightful living, and enable high talent not to go to waste. And the point that I know him for is his calling for positive psychology.

One distinction between Eastern Orthodoxy and Rome is that in Rome, all theology is systematic theology, and in Orthodoxy, all theology is mystical theology. This much is true to point out, however it invites confusion.

Thomas Aquinas, were he alive today, couldn't cut it for "publish or perish" academia. He is revered as one of the greatest giants in history, but he would not obviously be welcome as an academic today. While there are many ideas in his Summa Theologiae, few or any have the faintest claim to originality. Some people, including me, don't think that a single original idea is to be found. Others think that there are a few, very few: I have not read anyone attribute even a dozen original ideas in his quite enormous work. But what he did provide was a system: an organized set of cubbyholes with a place for everything and everything in its place. And the claim that all Roman theology is systematic theology means that everything fits somewhere in the system, whether Thomas Aquinas's or something else.

The claim that all theology in Orthodoxy is mystical theology is a different sort of claim. It says that all true theology meets a particular criterion, like saying that all true fire brings heat. It is not a claim that everything fits under some kind of classification scheme. Systematic theology as such is not allowed, and trying to endow the Orthodox Church with its first systematic theology is a way to ask the Church heirarchy for a heresy trial. "Mystical" in mystical theology means theology that is practiced, experienced, and lived. The claim to "study" a martial art can involve reading, especially at the higher levels, but if you are going to study karate, you go to a dojo and start engaging in its practices. In that sense, while books may have some place in martial arts mastery, but "studying" ninjutsu is not something you do by burying your nose in books. It is a live practice.

All theology is positive theology, and my assertion is like saying that all theology is mystical theology, and not that all theology is part of systematic theology.

As to the relationship between positive psychology and positive theology, I honestly hope for an interesting conversation with some of the positive psychology community. I do not assert that positive theology contains positive psychology as we know it, or that positive psychology contains positive theology. I do, however, wish to suggest that something interesting and real is reflected in the claim that all theology is positive theology.

I wish to make one point of departure clear in the interest of framing what I am attempting.

There is a certain sense that this work could be seen as novel; for all I know it may be the first work discussing all Orthodox theology as being positive theology, but I follow Chesterton's footsteps here (or rather fall short of them). I am not seeking to invent a positive theology. I am in fact attempting no novelty of any sort other than a new articulation of timeless truths that are relevant to the conversation. And I am seeking to offer something better than something wonderful I invented. I want to talk about wondrous things that I believe God invented, as old as the hills.

What is positive in the psychology of the Orthodox Church? To get off to a good start, I would like to say "repentance from sins." And one of my articles unfolds in Repentance, Heaven's Best-Kept Secret.

The Philokalia says that men hold on to sin because they think it adorns them. Repentance is terrifying. It is an unconditional surrender. But once you have made that surrender, you receive a reward. You realize that you needed that sin like you need a hole in the head—and you are free of a trap. It is something like a spiritual chiropractic massage, that you walk away from in joy with a straighter spine. And in my own experience, I'm not sure I am ever as joyful as when I am repenting. And the effect is cumulative; repentance represents a rising spiritual standard of living. Repentance is like obediently showing up for your funeral, and then you get there and you have shown up for your resurrection.

Monasticism, which I discuss in A Comparison Between the Mere Monk and the Highest Bishop, represents a position of supreme privilege within the Orthodox Church. Now I love my Archbishop dearly and wouldn't want to take him down one whit, but part of the point of the piece is that if you are given a choice between being the greatest bishop in the world and being an ordinary monk, "ordinary monk" is hands down the better choice to choose. The overriding concern in that environment is the spiritual, human profit of its members. Poverty, obedience, and chastity are all conditions to one of two routes to salvation, and however wonderful marriage may be, monasticism is even better. And as well as other terms, monasticism is spoken of as "repentance." To live in a monastery is to work at a place that is minting spiritual money and giving all members as copious pay as possible.

Robert Goudzward, in Aid for the Overdeveloped West, talked about Old Testament law as representing a paradise, and part of the picture is that it represented a paradise in which it was hard to get rich. A sage in the Bible asks, "Give me neither poverty nor riches," and there is a sense that having more and more money is not good for us as humans.

This world was created to be a paradise. The Old Covenant represented a paradise. The New Covenant represents a paradise. Marriage represents a paradise. Monasticism represents a paradise.

We were made for human flourishing, and part of what the Church attempts is to provide for each person to flourish as that person should flourish. Abbots (and everyone else) are not to colonize and clone; the authority is profound, but it is a profound authority in restoring a damaged icon—and helping the icon look like itself, not like something it isn't. If you read the saints' lives over time, all the saints represent Christ, but there is incredible diversity among how the saints represent Christ.

If we look at the question of what God commands and what he requests, there is fundamental confusion in thinking God is asking us to fill his needs. God in Heaven is perfect, and has no conceivable needs except in the person of our neighbor. God makes demands of us, not to fill his needs like an incompetent therapist, but to give us what is best. St. Maximus the Confessor divides three classes of obedience: slaves, who obey out of fear, mercenaries, who obey to obtain benefits, and sons, who obey out of love. Now all obedience is in at least some sense obedience and sometimes obedience out of fear is just what the doctor ordered, but if you obey as a slave you can be saved, if you obey as a mercenary you do better, and if you obey as a son even better than that. However, none of this is a setup to fill God's needs. The point is not that it is best for God if we obey out of love; the point is that it is best for us if we obey out of love.

This may come across very strangely to a psychologist who endorses affirmations, but the two main affirmations in Orthodoxy are "Christ died to save sinners, of whom I am first," and "All the world will be saved, and I will be damned."

Part of this stems from beliefs that I will explain but I do not ask you to subscribe to. Religion has enough of a reputation for focusing on the afterlife that it is provocative for a social gospel poster to say, "We believe in life before death." This life is of cardinal and incomparable significance; it is a life in which inch by inch we decide whether we will embrace Heaven or Hell when our live ends and no further repentance is available. But it has also been said that birth and death are an inch apart whilst the ticker tape goes on forever, and reform is only possible before we die. What the "affirmations" (of a sort) that I have mentioned do is prepare people like plaintiffs to press forth for maximum awards in their favor. The statements are for our good, and they help before death. Furthermore, it is believed that God doesn't do everything in our good works for us, but he allows a genuine cooperation of combined powers where we do part of it. We are told, though, that we are not to take credit for one single achievement in our life, but give all the merit to God... but come Judgment Day, all good deeds we have done our part to are reckoned as if we did them entirely ourselves and without any help from God. I do not ask you to believe this or think it makes sense, but I suggests it is a part of a picture where an overriding concern is God blessing us as much as we will accept.

Dr. Seligman's lecture linked at the beginning of this article talked about how French vanilla ice cream tastes exquisite for the first bite, but by the time you get to the fifth or sixth bite, the flavor is gone. In the first candidate for the good life, people habituate quickly.

I have slightly opposite news about Orthodox affirmations: when you make them central to your life, the sting crumbles. Furthermore, if you see yourself as the worst sinner in a parish, or a monastery, or all prehistory and prehistory, that's the time that real growth and even real joy appear. Orthodoxy's affirmations unlock the door to repentance, and there is no end of treasure to be mined from that vein.

I've seen TED talks about how stoicism is being taken as some sort of ultimate power tool, and secret weapon, within the professional NFL community.

Part of my thought was, "Duh!" and with it a thought that it is a mischaracterization of philosophy to assume it's just something for odd and eccentric people, including yours truly, who have their noses in books. Stoicism is legitimately a power tool, but it is one of many power tools that have garnished quite a following and have been as powerful to their practitioners might have been.

I have said elsewhere, "Orthodoxy is pagan. Neo-paganism isn't," and The Philokalia preserves the very best of pagan philosophy with its profound endowment of virtues. N.B. the same word in Greek means "virtue" and "excellence," and if you want to help people thrive and develop giftedness, the four-horsed chariot of courage, justice, wisdom, and moderation has really quite a lot to go for it, and all the more if these are perfected by the virtues of faith, hope, and love. All of these are called "cardinal" or "hinge" virtues, meaning that not only are they good, but they are positive "gateway drugs" to other and perhaps even greater virtue.

And I would like to say one thing that the authors of The Philokalia simply can't much of ever stop talking about. This does not seem an view of yourself that you would want to have, but I've had some pretty arrogant and abrasive people try pretty hard to teach me about humility. But I will say this: humility is the Philosopher's Stone and maybe the Elixir of Life. It opens your eyes to beauty pride may not see, and I need humility in my daily living more than I need air. I'm not going to try to further argue for an unattractive virtue, but I will say that it looks tiny and constricted from the outside, and vast and spacious from the inside. And for another Chesterton name drop: "It takes humility to enjoy anything—even pride."

If we are going to look at world traditions, the Greek term for virtue, arete also meant excellence, and arete (I both mean 'virtue' and 'excellence') represents a tradition well worth heeding. Bits and pieces have been picked up on TED talks; Stoicism is a power tool among the professional American football community, and another TED talk talks about how "grit" (also known as fortitude or courage) makes a big difference in success. But the tradition of virtue itself, and virtue philosophy, is worth attention.

I haven't read the title, but I have read Fr. Richard John Neuhaus talk about his title The Naked Public Square, in which he argues essentially that a religiously neutral public square is an impossibility, and the attempt to produce a naked public square will, perhaps, result in a statist religion.

If serious inner work without the resources of religious tradition is a possibility, I haven't seen it. Present psychotherapy has changed much faster than core humans have changed, and uses yoga practices from Hinduism, mindfulness of a sort (whether a traditional Buddhist would recognize Western exhiliration at mindfulness as Right Mindfulness I do not know), and a couple of other usual suspects like guided imagery (alleged to be known from Graeco-Roman times and known to some traditional medicines, although the pedigree seems to be copied and pasted across websites).

In my Asian philosophy class, I was able to sympathize with some element of almost everything that was presented. In terms of Hindu claims that inside each of us is a drop of God, I could sympathize, believing we are made in the image of God. But the one point I recoiled from is Buddhism's anatta, or an-atman: the claim that we, and everything that "exists", are an empty illusion. Or as Chesterton put it: "Buddhism is not a creed. It is a doubt."

Right Mindfulness, in its context in the Buddhist Eightfold Noble Path, is a cardinal virtue, and I count that as a positive. However, I do not see the need for the West to turn to India as a maternal breast. It is a microaggression that treats Orthodox Christianity as bankrupt of resources. I also don't like being advised to practice yoga. I am already participating in a yoga, or a spiritual path: that of Orthodox Christianity, and it is a complete tradition.

My point, however, is not to attack the medicinal use of Indian tradition (whether or not Indians would recognize their land's spiritualities), but to say that value-free counseling is something I have never seen, and while it may be politically correct to foist Indian spirituality but not Orthodox Christian, I wish to offer a word on my drawing on my religious tradition. Whether you accept it is not up to me, but Orthodoxy is a therapeutic tradition. And the claim has been explicitly made, in a book called Orthodox Psychotherapy, that if Orthodox spiritual direction were to appear new on the scene today, it might well not be classified as "religion," but as "therapeutic science."

I have not been directly involved with that therapeutic science. I've tried to reach monasticism, and am still trying, and therapeutic science is included in monasticism. So I cannot directly speak from experience about its fruit. But other things—virtue, repentance from sin and the like, I can directly attest to as positive theology.

Humility seems at the start something you'd rather have other people have than have it yourself. It looks small on the outside, but inside it is vaster than the Heavens, and it is one of two virtues that the virtue-sensitized Fathers of the Philokalia simply cannot ever stop talking about.

Perhaps what I can say is this. I don't know positive psychology well, but one of the first lessons, and one of the biggest, is to learn and express gratitude. And what I would say as someone who believes in gratitude is this: what gratitude is to positive health, humility is more.

Let me ask a question: which would you rather spend time with: someone horrible and despicable, or someone wonderful and great? The latter, of course. How it relates to humility is this: if you are in pride, you see and experience others as horrible and despicable, while if you are in humility, you see others as wonderful and great. Church Fathers talk about seeing other men as "God after God." That is a recipe for a life of delight.

There is more to be said; I am quite fond of St. John Chrysostom's A Treatise to Prove that Nothing Can Injure the Man Who Does Not Injure Himself. In connection with this, there are constant liturgical references to "the feeble audacity of the demons." The devils are real, but they are on a leash, and we are called to trample them. It has been said that everything which happens has been allowed either as a blessing from God, or as a temptation. (In Orthodoxy, "temptation" means both a provocation enticing to sin, and a situation that is a trial). As has been said, the faithful cannot be saved without temptations, and the temptations that pass are provided by God so we can earn a crown and trampling them. St. John here frames things in a very helpful way.

Here I am starting to blend into something other than positive theology, and making assertions about positive theology and how they have similar effects to positive psychology. But really, all is ordained for us by a good God, a point for which I would refer you to God the Spiritual Father. There is profound providence, and profound possibility for profit, if only we have eyes to see it and be grateful for a God who has ordained Heaven and Earth for the maximum possible benefit for each of us. Does this strain credibility? Yes, but I believe it, and I believe it makes a world of difference.

The article form of my advisor's thesis offered a case study for an understanding of se cularity, and his case study was in psychology. He talked about how an older religious concept of passions was replaced by what was at first a paper-thin concept of emotions which you were just something you felt at the moment, then how the concept of emotions filled out and became emotions that could be about something, and then they filled out further and you could have an emotional dimension to a habit. The secular concept remains alienated from its religious roots, but the common Alcoholics Anonymous concept of being an alcoholic has almost completely filled out what was in the older concept of a passion.

I'm not completely sure secularism is possible; it returns to Hinduism, at least for yoga, and Buddhism, at least for Right Mindfulness, as maternal breasts, and Hinduisim has something there as Buddhism does not. Chesterton comes again to mind: "The problem with someone who doesn't believe in God is not that he believes nothing; it's that he believes anything!" I believe the Orthodox Church's bosom offers a deeper nourishment. I'm not sure I have much to back this claim other than by the extent by which this article does (or does not) make sense, or whether it is more desirable to pursue one virtue (giving that virtues are stinkin' awesome things to have), or pursue a panoply of virtues. But I would hope that the reader would by now be able to make sense of my assertion that all Orthodox theology is positive psychology, even if the claim is more superficial than the assertion that all Orthodox theology is mystical theology.

For further reading without a moment's thought to positive psychology as such, see The Consolation of Theology, a work of Orthodox theology, and one steeped in virtue philosophy.

From Falstaff to Herodotus, grace: I send your excellence my manuscript, as revised again, and have returned the Imaginarium. I have tried to envision what life was really like in The Setting, but yet also keep things contemporary. Please send my boots and cloak by my nephew.

Here is the story:

Oct 8, 2020, Anytown, USA.

Anna looked at the sky. The position of the sun showed that it was the ninth hour, and from the clouds it looked like about four or five hours until there would be a light rain.

She stood reverently and attentively, pulled out her iPhone, and used a pirated Internet Explorer 6 app to spend deliberate time on social networks: first Facebook, then Twitter, then Amazon. It was the last that offered the richest social interaction.

Technology in that society underscored the sacred and interlocking rhythm of time, with its cycles of lifetime, year, month, and day, right down to the single short hour. But there was a lot of technology, and it had changed things. The road had for ages been shared between pedestrian man and horse. Now, decades after automobiles had taken root, it had to be shared between man, horse, and motorcar. A shiny, dark Ford Ferrari raced by her on the sidewalk. She paused to contemplate its beauty. Then she listened, entranced, as a poor street musician played sad, sad music on an old Honda Accordion.

And in all this she was human. Neither her lord nor she knew how many winters each had passed when they married; neither she nor her lord for that matter knew that it was the twentieth century. She cared for birth and mirth, and she loved her little ones. She did not know how many winters old they were, either. And there was life within her.

And she was intensely religious, and intensely superstitious, so far as to be almost entirely tacit. She knew the stories of the saints, and attended church a few times a year. She lived long under religion's shadow. And her mind was tranquil, unhurried, unworried, and this without the slightest effort to learn Antarctican Mindfulness.

And in all this, she was content. Her family had lived on the same sandlot; more than seven generations had been born, lived, and died without traveling twenty miles from this root. The stones and herbs were family to her as much as men, but this was, again, tacit.

She was human. Really and truly human, no matter what others thought the epoch was.

Then a crow crowed. She looked around, thoughtfully. It was well nigh time to visit her sister.

"But how to get there?" she thought, and then, "I have walked in the opposite direction, and she will be upset if I am even two or three hours late."

Then a solution occurred to her. She reached into her pocket, pulled out her new iPhone Pro, pulled up the Uber app, and ordered a shared helicopter ride.