Jonathan: Hast thou not read my "Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God," in which I say that all of us, who have offended God, have no more power to stay God's casting us into Hell than a spider's web canst stay the torrent of a flood?

Dionysius: Of a truth, and there might be worse things be said.

Jonathan: Then thou knowest men to be sinners in the hands of an angry God.

Dionysius: The saying is limited and more limiting than thou wittest.

Jonathan: Which of my sayings is false? Have I not expounded Scripture, and that carefully?

Dionysius: Thou hast such in common with St Athanasius the Great, and with Arius, the father of heretics.

Jonathan: Then wherein is it wrong to speak of sinners in the hands of an angry God?

Dionysius: Hath God the Father material hands, such hands of clay such as we have?

Jonathan: My speech of hands is an anthropomorphism used to convey a truth.

Dionysius: Then perhaps it behooveth thee to recognize that speaking of God as angry is an anthropomorphism used to convey a truth.

Jonathan: How be it such? May it be the end of the manner that all we say is an anthropomorphism used to convey a truth?

Dionysius: All we can say of God has some truth, and all of it fails to be equal to the task of speaking its reality.

Jonathan: Is all a shade of grey?

Dionysius: To speak of shades of grey is not to paint all in an identical, centermost, most insipid mid-range of grey. All we say of God has some truth and some limitations, but it is not entailed that all has the same degree of truth and of limitation. Differing statements are unequal in splendor, and what they have is held in divers ways.

Jonathan: Then what is true, and what is false, in saying that all man's plans are but a spider's gossamer web in its impotence to restrain the wrath of God?

Dionysius: St John the Theologian hath not written, "God is wrath," and one who reads "Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God" receiveth no shade of invitation to contemplate the true wrath of God.

Jonathan: Then in what consisteth the wrath of God?

Dionysius: Hast thou read Fyodor Dostoevsky, The Brothers Karamatzov?

Jonathan: Let us say that have I not.

Dionysius: The book opens in nihilism, and Fyodor does not pull a single punch in letting the problem of evil rage as wildly as it can. Then it whispers at the end.

Jonathan: And what is that whisper?

Dionysius: The same whisper as in the Gospels, which portray in detail the Lord's mercy to Judas, letting him keep the purse to soothe his greed, and the betrayal with a kiss, the passion, and death of the Incarnate Savior in which all hope is dashed. Then a whisper announces, "Christ Is Risen!" and there is scarce any more to say.

Jonathan: Sayest thou that a spider's web can stay a surging flood?

Dionysius: I say rather that all the horrors of Hell, all devils' malice, all temptation, and all sin is but a spider's web too gossamer and flimsy to stop the surging flood of the Light and Providence of a Loving God.

Jonathan: It beseemeth me that thou speakest not of the gravity of sin. Sayest thou that God be unjust?

Dionysius: Let us say that I do.

Jonathan: Then what is thy secret?

Dionysius: In the Parable of the Talents, the wicked and lazy servant says of his Master, "Thou art an austere Man: Thou takest up that Thou layedst not down, and reapest that Thou didst not sow." And his Master contests him not a word.

Jonathan: That is a matter most perplexing.

Dionysius: Then let the passage be opened with the Spirit's breath. The Three Persons of the Trinity have not sown sin, nor sorrow, nor death. God hath not manipulated Judas, or for that matter Satan, to be instrumental to, in the phrase of St John the Theologian, "destroy the devil's work." Satan rebelled his worst against the God-man to prevent him from working, and even killed him. The God-man's answer never reverses what the devil did to him, but instead made it the earnest of the resurrection of all, who must die in that all have sinned.

Jonathan What? Deniest thou that society decayest now, when every evil is rising?

Dionysius: There was a time when the voices of prophet, priest, and king were all silenced. That was the moment when the most beautiful Song in the world was ever sung.

Jonathan: (After a pause.) And can such a God make use of even sins and errors such as mine?

Dionysius: Of this something is noised even from thine own camp. It is not just that thou canst be ten thousand steps away from God but it taketh only one step for thee to turn towards Him. Thou triest to do God's job for thyself and be thine own Providence, and thy Plan A falleth by the wayside, and thy Plan B is wrecked, and thy plan C goeth up in smoke before thou canst even set it in motion. And so thou failest, going down the alphabet. But God, whose Providential Love rests on thee, is only, always and ever dealing with thee on Plan A.

The story is told of a classical music concert set up when a little boy came up and started playing chopsticks. The musician came, and rather than send him away, placed his arms around the child and his hands around the boy's hands and began to improvise around what the boy was playing. And so it is with the God who is on Plan A.

Jonathan: And how can I know it?

Dionysius: Become thou a catechumen, and be thou baptized and chrismated into Christ's Holy Church...

...then dare to approach the Chalice, and receive Christ as ever thy Lord and Savior, and be thyself joined to His Holy Church.

Category: Fiction

An Author Interview by... the Author Himself!

Interviewer: You're interviewing yourself? Some of your opponents might say that's a bit odd and egotistical. I'd like to give you a chance to respond to what your opponents are saying.

C.S. Hayward: Um, well, yes, I have plenty of ego, and this is a bit unusual, and some people who know me might find it a surprise, if perhaps a believable surprise. But may I comment?

Interviewer: Certainly. What do you have to say for yourself?

C.S. Hayward: As far as denying that I am proud, I'm not interested in defending myself. If I am to be defended, and I am not innocent, my defense would best be spoken by others' lips. But as for a reason, I do have a particular practical reason for such an odd process.

Interviewer: What's that?

C.S. Hayward: Awesome Gang offers a free interview for an author to promote his book, and I can only call that a work of mastery for all kinds of authors offering all kinds of books. But there is a weakness in such a master-stroke: the cookie cutter allows discussion of the Scandal of the Particular, but I wished something almost entirely driven by suchlike scandal. I want questions that allow me to speak, and at times much more particular questions, even if (for instance) my website's author biography is very unusual for a personal biography:

Who is Christos Jonathan Seth Hayward? A man, made in the image of God and summoned to ascend to the heights of the likeness of God. A great sinner, and in fact, the chief of sinners. One who is, moment by moment, in each ascetical decision choosing to become one notch more a creature of Heaven, or one notch more a creature of Hell, until his life is spent and his eternal choice between Heaven and Hell is eternally sealed.

Man, mediator, midpoint, microcosm, measure: as man he is the recapitulation of the entire spiritual and visible creation, having physical life in common with plants and animals, and noetic life in common with rank upon rank of angel host, and forever in the shadow of that moment when Heaven kissed earth and God and the Son of God became Man and the Son of Man that men and the sons of men might become gods and the sons of God.

He’s also a writer with a few hobbies, but really, there are more important things in life.

Interviewer: What would you respond to people who say that's not really the scandal of particular!

C.S. Hayward: It draws attention to something overlooked in a standard statement of what makes your uniqueness, as marketers would have it. I claim for myself the glory and the shame of being human. And I stand indebted to one monk who had managed some prestigious obediences, but as far as the story of his coming to Orthodoxy, wrote, "The story of _________'s coming to Orthodoxy was told to the priest who received him, under the seal of confession, and he received absolution for his sins." And I can't really do better than that. Or rather, I have only said anything much better and much more specific than that under the seal of absolution. I've had an interesting life story, and other aspects are told in my autobiography, Orthodox Theology and Technology (my first impulse was to mention The Luddite's Guide to Technology, which I consider my work most likely to be significant). But the distinction I seek is in repentance, both in the sense of something all Orthodox are called to, and as a term for monasticism.

Interviewer: "Orthodox Theology and Technology?" Do you consider yourself a theologian?

C.S. Hayward: The story is told of a liberal scholar who went to the Holy Mountain and told a monk that he was a theologian, and the monk suddenly acted very obsequious and began kissing his feet. The academician asked why on earth the monk was acting that way, and the monk explained, "We had St. John the Theologian, and then some centuries later we had St. Gregory the Theologian, and then some centuries after that we had St. Symeon the New Theologian, and now, we have... you!

It is not a respected affirmation that one is the fourth in that series, but if I may speak for the "underdog perspective" (Fr. Seraphim of Platina said it is noble to defend the underdog), the standard Western use of "theologian," especially without the idea that you bracket any religious beliefs you have and work in theology in an atheistic approach, is a concept that has legitimate use, and in a devout Western setting the claim to be a theologian is not meant or taken as a claim to be the fourth of that august company that directly experience God. For that matter, the Philokalia talks about people engaging in "theology", meaning the direct experience of God and not the accumulation of the more usual kind knowledge concerning God.

Orthodoxy in recent years, to fill the gap of someone who works to understand God without the claim to be the fourth in that august company, has developed the term "patrologist" to mean someone who devoutly studies what academics trade in, and is the general term for someone who has not specialized in something with a more specific term. And I would claim to be a patrologist lite, perhaps not the best out there even in my interests. It's kind of a way of answering a Westerner's question of whether I study what a Westerner would consider theology, but without the implications of a claim to be the fourth Theologian in the Orthodox Church's history.

I was studying at an Orthodox seminary, but that seemed to get derailed because my need-based financial aid was not registered, and my strong hope is to get to St. Demetrios's monastery in Virginia whether it takes one trip or several, insofar as I am able to. I'm not sure if you've read Everyday Saints and Other Stories, but the words are fragrant with the fragrance of Heaven yet simple such I have rarely, if ever, pulled off myself. In that book, Orthodox seminarians tend to be arrogant and clueless, enough so that a seminarian who should know enough patristics to know that thC.e Orthodox Church claims a wealth of only three Theologians, introduces himself as a theologian and is surprised when he is asked, "You're the fourth?" And I wonder if having introduced myself as a seminarian I have introduced myself as arrogant and clueless in like terms.

Interviewer: Um, you're introducing yourself as "C.S. Hayward."

C.S. Hayward Yes, and may I say a few things about that?

First, I owe C.S. Lewis a greater debt than perhaps any mortal writer. I've read 90% of all he has written, including some of The Neglected C.S. Lewis, and he shaped me enough as an author that I've been told, "You write like an Englishman."

And there's also what Graham Clinton, founder of International Christian Mensa, said.

Interviewer: What's that?

C.S. Hayward: I asked him, in perhaps inexusable vanity, if I might be the next C.S. Lewis. His first reply could be taken as a very diplomatic "No." He said, "Sure, you could be, but why would you want to?"

But the next major point he tried to make was really about how the World Wars emphatically "killed off all our talent." He said simply that all the A-level talent in England got killed off, leaving B's like C.S. Lewis to be promoted when they would otherwise have had to work for a living (his term). The implication was that I was A-level talent wanting to be compared to B-level talent.

And on Facebook, which isn't too keen on having people known by initalism, entered my name as Christos Jonathan Seth Hayward, expecting it to be collapsed and yield "CJSH." Readers found enough kindness and affinity to condense to "CSH" meaning, "C.S. Hayward." So why not?

Interviewer: So what has life been like? I noticed that you are applying, at 46, to a monastery that's looking for novices in their 30's.

C.S. Hayward: Yes; may I say a word about that?

Interviewer: Certainly.

C.S. Hayward: That is not simply an arbitrary or superstitious requirement; they are presumably looking for people who still have a certain flexibility to be able to adjust to monastic ways. And may I speak about that?

Interview: Yes.

C.S. Hayward: The mainstream understanding of learning languages is that languages are best learned as a child, and not as an adult. However, this is a rule of thumb and not an unyielding principle. The usual course of language development is to learn one's first language, and then redeploy the grey matter that can learn languages once no new languages are being learned. But I've continued to learn languages, if not always very well, and at Cambridge I was told I was learning Greek as a child did. And when I took the modern languages aptitude test, as an adult, I scored (mumble) and was told for instance, "I've been scoring this test for thirty years and I've never seen a score this high." I have master's degrees in math and "theology." Both were interdisciplinary, and both were from a world-class institution: UIUC and Cambridge.

I don't want to mindread or psychologize what would motivate a monastery to make such a request, since retirees have become successful monks, but the obvious concern is a rational one: the monastery may prefer candidates who are not too set in their ways to adapt to monastic life.

And I have continued to have changing life circumstances: studying and returning to school, ineptly fitting recruiter roles in information technology, and retirement on disability. I was able to survive for two years studying theology at Fordham, and I have continued to make major adjustments every few years ago. So I believe I could age-wise be accommodated to monasticism. I've kept alive the ability to adjust to different circumstances as I've kept alive, at least badly, the ability to learn languages (and have read the Bible in English, French, Spanish, Latin, Greek, Slavonic, and modern Russian and just dipped into Ukrainian). I have a T-shirt that says, "Я ез США. Говорите медленное пожалуеста" ("I'm from the USA. Please speak slowly.").

Interviewer: Who made it?

C.S. Hayward: I did, and I've been clearly advised not to wear it to a Slavic monastery. I might still use it as a night mask or as an undershirt.

Interviewer: I've just taken a look at Profoundly Gifted and Orthodox at Fordham. Eek! What sense did you make of that?

C.S. Hayward: The biggest is that the forces of evil only have a hand on me so far as I disobeyed. The first time they needlessly endangered my life, it was strongly in my conscience to complain to the President of the university. I failed to do so; had I obeyed, I might have had a channel open when things went really wrong. Also, I tried the hardest of my life to befriend the great Fr. John Behr, identified as A____ in the document. My conscience was to give him a wide, wide berth. My faults ratified others' decisions and failings.

But there is one thing I would like to clarify.

Interviewer: Yes?

C.S. Hayward: I haven't ever really been off-track except as... I may have tried plan A to get a Ph.D., and then a plan B, and then a plan C, and so on down the alphabet, but my as my spiritual director told me during one of our first meetings, God is always on plan A, even if we think we're going down the alphabet. Even if I never succeeded at further entering a doctoral program or getting an academic position, even a community college adjunct professorship at a large College of DuPage.

Interviewer: You think you're on a Plan A?

C.S. Hayward: Bookmark and read God the Spiritual Father sometime. I am not on my own Plan A, but God is on Plan A. The International Christian Mensa Founder's unfailing, ever-polite requests for me to wake up, said, "Your job is not to write the books that PhD's write. Your job is to write the books that PhD's read." And I have written books for scholars and nonscholars, gently suggested that Fr. John's St. Vladimir's Seminary can stop sucking Fordham's staff, in more ways than one. (I've gone through that discipline myself).) I have also had a whole lot of being in the right place at the right time. My website is enormous, with a print "Complete Works" series that occupies eleven volumes of four to six hundred pages, and that's a dense four to six hundred pages per book. Not all of it is excellent, but some are pretty good.

Interviewer: Sounds like you've shined through some pretty rough stuff.

C.S. Hayward: I have a lot to be grateful for, and not just in relation for my writing. I have a covered dental visit coming up where I'll end up with a root canal, crown, and partial being paid for. You may say that a root canal is little to be excited about, but really, having dental work covered is something to be grateful for.

Interviewer: And you are grateful.

C.S. Hayward: I am not worthy or capable of thanking God adequately for all the good he continues to show for me. But I give praise, even when I am unworthy to give praise.

And I am glad to be visiting the monastery. I don't know if they will require multiple visits, or whether they'll follow a practice on the Holy Mountain and allow me to come as a pilgrim and stay as a novice. But in any case, the abbot's decision will be part of God's Plan A, even if I am not allowed to join. All that's really left to me is due diligence. And I'm working hard on the "due diligence" part, such as having a collection of pants with varying waist sizes so I'll have pants that fit me as my waist shrinks on a monastic diet. I'm really looking forward to it, I've been told the abbot is kind, and even if he makes a decision I don't want him to make, God will still be on Plan A.

Onwards and Upwards, as we said at Avery Coonley School!

Hysterical Fiction: A Medievalist Jibe at Disney Princess Videos

From Falstaff to Herodotus, grace: I send your excellence my manuscript, as revised again, and have returned the Imaginarium. I have tried to envision what life was really like in The Setting, but yet also keep things contemporary. Please send my boots and cloak by my nephew.

Here is the story:

Oct 8, 2020, Anytown, USA.

Anna looked at the sky. The position of the sun showed that it was the ninth hour, and from the clouds it looked like about four or five hours until there would be a light rain.

She stood reverently and attentively, pulled out her iPhone, and used a pirated Internet Explorer 6 app to spend deliberate time on social networks: first Facebook, then Twitter, then Amazon. It was the last that offered the richest social interaction.

Technology in that society underscored the sacred and interlocking rhythm of time, with its cycles of lifetime, year, month, and day, right down to the single short hour. But there was a lot of technology, and it had changed things. The road had for ages been shared between pedestrian man and horse. Now, decades after automobiles had taken root, it had to be shared between man, horse, and motorcar. A shiny, dark Ford Ferrari raced by her on the sidewalk. She paused to contemplate its beauty. Then she listened, entranced, as a poor street musician played sad, sad music on an old Honda Accordion.

And in all this she was human. Neither her lord nor she knew how many winters each had passed when they married; neither she nor her lord for that matter knew that it was the twentieth century. She cared for birth and mirth, and she loved her little ones. She did not know how many winters old they were, either. And there was life within her.

And she was intensely religious, and intensely superstitious, so far as to be almost entirely tacit. She knew the stories of the saints, and attended church a few times a year. She lived long under religion's shadow. And her mind was tranquil, unhurried, unworried, and this without the slightest effort to learn Antarctican Mindfulness.

And in all this, she was content. Her family had lived on the same sandlot; more than seven generations had been born, lived, and died without traveling twenty miles from this root. The stones and herbs were family to her as much as men, but this was, again, tacit.

She was human. Really and truly human, no matter what others thought the epoch was.

Then a crow crowed. She looked around, thoughtfully. It was well nigh time to visit her sister.

"But how to get there?" she thought, and then, "I have walked in the opposite direction, and she will be upset if I am even two or three hours late."

Then a solution occurred to her. She reached into her pocket, pulled out her new iPhone Pro, pulled up the Uber app, and ordered a shared helicopter ride.

Beware of Geeks Bearing Gifts

Why did we call ourselves the Katana? It was in the excitement of a moment, and a recognition that our project has some off the elegance of a Katana to a Japan fan. We were more current than today's fashions and for that matter made today's fashions, but representing an unbroken tradition since Plato's most famous work, what they call the world's oldest, longest, least funny, and least intentional political joke: The Republic. Things would have been a lot easier if it weren't for them. They obstructed the Katana.

The Katana have a dynamic thousand-or-so goals, but there is only one that counts: the relentless improvement of the Herd. Some of the older victories have really been improving agriculture what seems like thirty, sixty, or a hundredfold, with mechanized engineering for farming and a realization that you can have meat costing scarcely more than vegetables if you optimize animals like you'd optimize any other machine, under conditions that turn out to be torture for farm animals. There are some lands where the Herd has been imbued with enough progress that the middle class has about as many creature comfort as there is to be had, and for that matter among the poor the #1 dietary problem is obesity. Maybe we made the Herd look more like pigs, but please do not blame us! We aren't eating that much!

And we are altruists through and through.

We have been providing the Herd with progressively greater "space-conquering technologies", as they are sold, which neuter the significance of their having physical bodies and the structure of life that was there before us. First we gave gasoline-powered Locomotives and great Aerobirds, devices that could move the meat of the human body faster. Now we are unfolding another wave of body-conquering technologies, which obviate the need to move meat. They are powered by a kind of unnatural living thing. Perhaps the present central offering in this horn of plenty, or what we present as a horn of plenty, is a Portal: a small device carried by many even in the poorest lands, that draws attention to itself and such stimulation it offers, disengaging from ancient patterns of life.

Things would be so much easier if it weren't for them. We tried to tell people that they hate women; now we've told people that they hate gays. They still get in the way of progress.

Yesterday there was a planned teleconference, a town hall among the Katana after an important document from them had been intercepted. It was encrypted with a flawed algorithm, but cryptanalysis is easy and semantics is hard, and we gave the document to the semanticians for analysis.

The title of the document was straightforward and one that the Katana was happy to see: "How to Serve Man". But the head semantician came late, and his face was absolutely ashen. It took him some time to compose himself, until he said—"The book... How to Serve... How to Serve Man... It doesn't contain one single recipe!"

[With apologies to Damon Knight, To Serve Man.]

That Hideous Impotence

Thimble even maintained that a good critic, by his sensibility alone, could detect between the traces head-knowledge and heart-knowledge had left on literature. "What common measure is there between IT hackers with their obscure and esoteric interests, their unworldly collections of skills that ordinary mortals scarcely even hear of, their attendant servers and daemons, and figures like the saints, who seem to produce results simply by trusting and following God?" Heart-knowledge and head-knowledge differ profoundly; heart-knowledge (though this is doubtful) may be as difficult to acquire; it is certainly a better exercise of the whole person.

The NASTY (the NASTY Association for the Scientism and Transhumanism Y-combinator) had, in a spirit of jest, one member occasionally call another member "more evil than Satan himself." But in fact the many members fitting into NASTY had one-by-one filled in pieces: now by FaecesBook, now by the Twits' Crowd, now by dark Goggles, now by MicroSith, now by Forbidden Fruit, all offering such treasures that in countries as poor as Africa, No Such Agency would know not only every web search and every text, but to any who could obtain a smartphone and a watch, every step, every breath, every heartbeat.

As time passed on, the technological dragnet only drew tighter. And people naturally think that all of this is the creative genius of man.

But there was always, always individual human freedom.

"It is rather horrible. The newer technologies together represent something like a secularized occult. I mean even our time (we come at the extreme tail end of it), though you could still use that sort of technology innocently, you can't do it safely. These things aren't bad in themselves, but they are already bad for us. They sort of withered the person who dealt with them. On purpose. They couldn't be adopted by the masses if they couldn't. People of our time are withered. Some millennials are quite pious and humble and all that, but something has been taken out of them. Take away their gadgets for a day and they will show a quietness that is just a little deadly, like the quiet of a gutted building. It's the result of having our minds laid open to something that broadens the environment.

"Orthodoxy is a last and greatest view of an old order in which matter and spirit are, for a modern point of view, confused. For some saints every operation on Nature is a kind of personal contact, like coaxing a child or stroking one's horse. Now we have the modern man to whom Nature is something dead—a machine to be worked, and taken to bits if it won't work the way he pleases, and postmodern varieties with their 'spirituality' which drives ever much deeper the chasm separating the sacred from the secular. The Orthodox Church, with her saints, represent what we've got to get back to do and an ever-open door. Did you know that Orthodox are all forbidden to pursue systematic theology?"

But Redemption already knew, in fact, that there was Eldilic energy and Eldilic knowledge behind the NASTY. It was, of course, another question whether the human members knew of the dark powers who were their real organisers. And in the long run this question was not perhaps important. As Ransom himself had said more than once, "Whether they know it or whether they don't, much the same sort of things are going to happen. It's not a question of how the human members of NASTY will act—the Dark-Eldils will see to that—but of how they will think about their actions."

For Redemption already knew of the constant stings of temptation come to all of us and try to entice us to believe ideas we think our own and embrace to our slow spiritual depth. The Philokalia, second only to the Bible among Orthodox classics in recent history, was a manual on the spiritual life that kept returning to the activities and operations of demons. Its authors know well enough about the continuing warfare of thoughts to desire this or that that have been assaulting us for the ages, and demonic temptations occur not only to some rare specialty of people deeply enmeshed in e.g. the occult. (And we are briefly told, "Men hold on to sin because they think it adorns them.") Demonic possession through occult or other means is of course a worse problem, but whether we like it or not a great deal of what we think of as our thoughts and our desires are stings of demons attacking us. As one student had approached Redemption and said, with great excitement, "I've just had a completely new idea," Ransom answered, "I am very excited for you and for your having this new idea. However, this idea was had before by Such-and-such particular monk in the fourth century, and furthermore he is still wrong."

Redemption opened The Luddite's Guide to Technology and called out:

A HYMN TO ARROGANCE.

The Saint opened his Golden Mouth and sang,

‘There be no war in Heaven,

Not now, at very least,

And not ere were created,

The royal race of mankind.

Put on your feet the Gospel of peace,

And pray, a-stomping down the gates of Hell.

There were war in Heaven but ever brief,

The Archangel Saint Michael,

Commander of the bodiless hosts,

Said but his name, "Michael,"

Which is, being interpreted,

"Who is like God?"

With that the rebellion were cast down from Heaven,

Sore losers one and all.

They remain to sharpen the faithful,

God useth them to train and make strength.

Shall the axe boast itself against him that heweth therewith?

Or shall the saw magnify itself against him that shaketh it?

As if the rod should shake itself against them that lift it up,

Or as if the staff should lift up itself,

As if it were no wood.

Therefore be not dismayed,

If one book of Holy Scripture state,

That the Devil incited King David to a census,

And another sayeth that God did so,

For God permitted it to happen by the Devil,

As he that heweth lifteth an axe,

And God gave to David a second opportunity,

In the holy words of Joab.

Think thou not that God and the Devil are equal,

Learnest thou enough of doctrine,

To know that God is greater than can be thought,

And hath neither equal nor opposite,

The Devil is if anything the opposite,

Of Michael, the Captain of the angels,

Though truth be told,

In the contest between Michael and the Devil,

The Devil fared him not well.

The dragon wert as a little boy,

Standing outside an Emperor’s palace,

Shooting spitwads with a peashooter,

Because that wert the greatest harm,

That he saweth how to do.

The Orthodox Church knoweth well enough,

‘The feeble audacity of the demons.’

Read thou well how the Devil crowned St. Job,

The Devil and the devils aren’t much,

Without the divine permission,

And truth be told,

Ain’t much with it either:

God alloweth temptations to strengthen;

St. Job the Much-Suffering emerged in triumph.

A novice told of an odd clatter in a courtyard,

Asked the Abbot what he should do:

"It is just the demons.

Pay it no mind," came the answer.

Every devil is on a leash,

And the devout are immune to magic.

Thou shalt tread upon the lion and adder:

The young lion and the dragon shalt thou trample under feet.

The God of peace will soon crush Satan under your feet.

Wherefore be thou not arrogant towards men,

But be ever more arrogant towards devils and the Devil himself:

"Blow, and spit on him."‘

And Redemption agreed. He said, "Faecesbook's old-school database-like limit on specifying one's religion are constricted. The facilities are sorely lacking to give one's religion as, "Alter Christus: "Follower of Jesus" means "Another Christ!""

Thimble asked, "And what of the Arthurian legends?"

Redemption said, "What about them?"

Thimble said, "Please, I want to hear."

Redemption said, "Well, one can say that there is no option to achieve the Holy Grail, nor to acquire it. The only game in town is to become the Holy Grail. But that is on the periphery."

iPun said, "I'm no literary critic, nor do I know about the Holy Grail, but it sounds an awful lot to me like you're holding out on us for an answer."

Redemption said, "Perhaps the most damning remark about medieval literature is that of all that one of the greatest literary legacies, and the only one on ordinary non-medievalists' radar, is that of the Arthurian legends."

Thimble said, "Could you be a little more concrete?"

Redemption said, "Take the figure of Merlin. His name, rendered as 'Myrddhin' in Lawhead's account, was changed to 'Merlin' in the Brut in order not to sound like a French swear-word, today 'merde.' The Brut, formally the Historia Regum Britanniae, is a twelfth-century example of history as society would like it to be, like some conspiracy theory works today, which is to say that is pseudo-history that today would ordinarily be introduced as fiction, with masterful storytelling but no connection to actual history. Also, the legends were importantly no longer offered in Celtic language, but Latin that could quickly spread through Europe. The legends spread like wildfire through Europe even centuries later, and interestingly spread in the vernacular, possibly carried by the troubadours who would inspire the name of Francis of Assisi.

"But about Merlin specifically. There have been efforts to Christianize him, and not just in recent history: Robert de Boron represents a medieval teller of Arthurian tales who tried to anchor them to Christian doctrine. In Sir Thomas Mallory, the hinge between the medieval flourishing and almost all subsequent English retellings of the legend, Merlin is not called a 'wizard,' but a 'prophet.' There is in the medieval legends pseudo-Christian working out of pseudo-doctrine that the Devil was to have a son by an almost-perfect virgin who had slipped in her prayers but once, and he would be something like an incarnate Anti-Christ, but Christians fortunately got wind of this and said many powerful prayers, to the effect that Merlin was born the Devil's son, but without the Devil's evil, so someone who commanded the Devil's power was yet good and Christian. And the same is to be said of C.S. Lewis, in whom we read:

"And where would Merlin be?"

"Yes. He's the really interesting figure. Did the whole thing fail because he died so soon? Has it ever struck you what an odd creation Merlin is? He's not evil: yet he's a magician. He is obviously a druid: yet he knows all about the Grail. He's 'the devil's son': but then Layamon goes out of his way to tell you that the kind of being who fathered Merlin needn't have been bad after all. You remember: "There dwell in the sky many kinds of wights. Some of them are good, and some work evil."

"It is rather puzzling. I hadn't thought of it before."

"I often wonder," said Dr. Dimble, "whether Merlin doesn't represent the last trace of something the later tradition has quite forgotten about—something that became impossible when the only people in touch with the supernatural were either white or black, either priests or sorcerors.

"Perhaps like no other character in literature, C.S. Lewis's Merlin is 'the really interesting figure.' He rivets all attention on himself, and for good reason. The standard distinction between flat and rounded characters in literature has said to be that a rounded character believably surprises the reader. Merlin comes remarkably close to delivering nothing but believable surprises.

"And Lewis has Merlin, and reference to being the Devil's son; the opening prehistory of the main story has a figure say, 'Marry, sirs, if Merlin who was the Devil's son was a true King's man as ever ate bread, is it not a shame that you, being but the sons of bitches, must be rebels and regicides?', but even Amazon reviewers have asked why Lewis has Merlin come if he's not allowed to do anything. And indeed one monumental goal when the Pendragon speaks with him is to shut down every single service Merlin offers to do for him (and finally corner him into one terrifying service)."

Thimble said, "Well and done, but does that one character tarnish into oblivion the entirety of the encyclopedia's worth of Arthurian legends that have been written?"

Redemption paused, and said, "Now that you mention it, I think it does in a much more direct way than I expected."

Thimble said, "How's that?"

Redemption said, "The Arthurian legends represent a never-never land to us, but it shows historical insensitivity to assume that they were realistic fiction to the Brut's first audience, or Chrétien de Troyes, or Sir Thomas Mallory. The Arthurian legends were a never-neverland when the ink on those pages was still wet: a land in which anything can happen, at least anything wondrous or supernatural. Commerce never sullies the pages, and one of very few peasants to get a physical description has a striking description that seems to describe a pachyderm more than any human. The dates for Arthurian legends to spread through Europe like wildfire are twelfth century and following, but the dates given as ostensible historical references for the original events are fifth or sixth century. In other words, the medievals telling the legends lived about as far after Arthur's supposed time as we are after them. There are a similar number of centuries in between.

"Furthermore, you get comments, in relation to chivalry and courtly love, that 'People don't really love nowadays, not like they loved then,' which is a perfect recipe for the same thing as you get today in the Orthodox Church with a nuclear family all wearing cassocks like monks and priests, and having an Irish last name. It's an attempt to re-create a past that never existed, and that is a gateway drug not just to silliness but trouble."

Thimble said, "Yes, but are stories about never-never land really as bad as a baptized Merlin?"

Redemption said, "I'm trying to think of a pleasant analogy. An unpleasant analogy might be to ask if soft porn is really as bad as hard porn. We ought ideally steer clear of both.

"In the desert, monks were perennially warned of the danger of escapism. When escape seems like something we need, it is a temptation, and the proper way of dealing with it is to keep on praying. Escape and the occult both have a sense that we know better than God what circumstances we should be in, and not see the here and now as a gift from God the Father. The whole temptation is a hydra. Whatever else Muslims have wrong, there is a very good reason why, historically, Muslim science may have been very good at observation, but very bad at entertaining competing theories: the basic objection is, in Christian terms, 'How can you want anything but what God in his Sovereignty has willed?' And this repugnance stems from something Western Christianity has lost in its transition to modernity.

"And this is why Lewis's distinction between 'fairy magic', meaning fairy-tale magic, which he saw as harmless and most often supplying plot devices, and 'real magic', meaning realistic depiction of occult practice, which he condemned, does not hold well enough. Of course the distinction is to be made, but when one reads the Chronicles of Narnia and reads Aslan saying, 'This was the very reason why you were brought to Narnia, that by knowing me here for a little, you may know me better there,' one wants to be in Narnia in escape and not to set down Narnia to experience real joy. To wish to be in Narnia represents the same passion, in the classical sense, as to wish to be Merlin.

"And if a tree may be judged by its fruit, the many fantasy authors who have followed Lewis in writing medieval fantasy have scarcely understood medieval history or been Christians, writing for Christian edification. Even as far as escape goes, Aslan sends all the children back from Narnia to our world, and says that trips to Narnia are only appropriate up to a certain age. In some subsequent works, the traveler from our world never returns: he remains in escape."

Thimble asked, "So we're best off leaving the Arthurian legends, and Merlin, with the medieval world?"

Redemption said, "I have trouble answering that question Aye or Nay."

Thimble asked, "Why? You see shades of grey?"

Redemption said, "No. I don't believe we've left the medieval world."

Thimble asked, "How's that?"

Redemption said, "I don't believe we've left the medieval world. I believe we've delved deeper into it than any figure who died before modern or postmodern history. If you know anything about how the katana—the sword that was called the soul of the samarai—is made, you would know that a smith makes a particular iron block, then stretches it and folds it in on itself, then that is hammered until it is stretched out, then folded in on itself, and the process is repeated many, many times. When the manifold steel is shaped into a sword, the blade is sharp as a razor, incredibly strong, and will last for ages, perhaps for centuries. The medieval West, isolated from the Greek Fathers, then later on infatuated with "the Philosopher" Aristotle to Thomas Aquinas's own great harm, and with its stream of Renaissances, represents that block of steel stretched out and folded in on itself. The chain continues for more than the more spectacular eccentricities to be found in the postmodern world. But the future sword blade stretched out and folding in on itself is a process of and by the medieval world, and a process that will perhaps continue until that terrible day when the Lord comes again in glory to judge the living and the dead—and may help pave the way for it!"

iPun said, "Do you not make allowances for greater ignorance in the past?"

Redemption said, "I do not make any allowance for greater ignorance in the past, although allowances for different ignorance in the past are more negotiable. You, personally, would do well to make allowances for greater ignorance in the present."

iPun said, "Do you not deny that we live in the ongoing wake of an explosion of knowledge in the sciences?"

Redemption said, "Knowledge can be ignorance. There has been a shift, as the steel has folded in on itself, of moving from heart-knowledge, knowledge of the whole person, to head-knowledge, to a knowledge that in its proper use serves as a moon to the sun of heart-knowledge. And in that sense we have gone from seeing by sunlight to being expert at seeing by moonlight. In the heyday of Arthurian legends, Rome warned its members about "idle romances," and even someone as foundational as Chrétien de Troyes has a privileged woman reading a romance on top of a sweatshop. As far as an explosion goes, we are spiritual heirs to the wreckage of a bomb exploding, so that even in Africa it is common to have multiple mobile devices per house. Lewis wrote of the press as spewing Western venom across the world; we've done his press one better, or perhaps many better for that. And the press of his day did not match the vile content on the web, nor accept as normal the intrusion of unsolicited porn, except that today you need a pill to make love.

"It is as if you stopped using the light of the sun himself, and would only see by the light of the moon, and as events unfolded you regained the natural human ability to see truly but imperfectly by the light of moon and star, and then you invented night vision systems that let you see by infrared indication of heat, or the little bit of green light that takes the lion share of natural light by night, and then to your pride combined them to make one cadaverous combination. And in all of this you remain in Plato's cave, and will not step out in the light of the sun, and not only because the people who see by moonlight would call it lunacy if you helped them see by the light of the sun."

Thimble said, "And in the light only of the moon herself, intimacy itself turns artificial."

Redemption said no more.

Gain flipped the page of the book, and read:

...accounts of Satan as God's jester. For all of us do the will of God; that is not the question. The real question is whether we will do God's will as instruments, like Satan and Judas, or Sons, as St. Peter and St. John.

That is why Christians need not fear the Antichrist, even if he is knocking at the door. For Satan will ever remain God's jester, and though an Antichrist be possessed of God's jester or not, to Christians there is no Antichrist and Christ is ever present to those who only "keep their eyes on Jesus." Do you fear not being able to buy and sell if you do not accept the Mark of the Beast on your hand and forehead? Know then that, as is said in the Philokalia, a man can live without eating (or drinking) if God so wills? Do not worry that the grace of God which so strengthened the martyrs in ages past need fail if you cannot buy bread or perhaps water. God is merciful, and no one can use force to stop God from being gracious to you. Remain faithful, that is all. Christians may, in the end, be saved simply because they refused the mark of the beast. Many monastics would have given everything to buy the grace of God at such a light price!

Gain heard footsteps on the floor behind the door, snapped shut the book and turned red, and then slowly opened it again.

Redemption laughed.

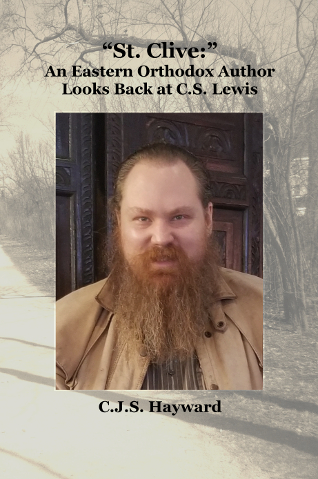

Read more of "St. Clive:" An Eastern Orthodox Author Looks Back at C.S. Lewis on Amazon!

The Consolation of Theology

Author's Note

This work is an intentional variation on Boethius's little gem of a classic: The Consolation of Philosophy (modern translation, old translation, another (old) translation online, wiki). It is like Plato: The Allegory of the... Flickering Screen?, but more deliberately divergent. This book is meant both to stand on its own and to take a road less travelled for the reader already acquainted with Boethius. For that matter, it is also intended in the tradition of another, lesser author following How Shall We Then Live?, following it with How Now Shall We Live?, and another author following Leviathan with Behemoth, and indeed how The Consolation of Philosophy has already been followed with The Consolations of Philosophy.

If you like to curl up with a good book, this is included in the collection The Best of Jonathan's Corner (Kindle, paperback), and I strongly encourage you to read the whole collection, perhaps starting with this piece.

Song I.

The Author's Complaint.

The Gospel was new,

When one saint stopped his ears,

And said, 'Good God!

That thou hast allowed me,

To live at such a time.'

Jihadists act not in aught of vacuum:

Atheislam welcometh captors;

Founded by the greatest Christian heresiarch,

Who tore Incarnation and icons away from all things Christian,

The dragon next to whom,

Arius, father of heretics,

Is but a fangless worm.

Their 'surrender' is practically furthest as could be,

From, 'God and the Son of God,

Became Man and the Son of Man,

That men and the sons of men,

Might become Gods and the Sons of God,'

By contrast, eviscerating the reality of man.

The wonder of holy marriage,

Tortured and torn from limb to limb,

In progressive installments old and new,

Technology a secular occult is made,

Well I wrote a volume,

The Luddite's Guide to Technology,

And in once-hallowed halls of learning,

Is taught a 'theology,'

Such as one would seek of Monty Python.

And of my own life; what of it?

A monk still I try to be;

Many things have I tried in life,

And betimes met spectacular success,

And betimes found doors slammed in my face.

Even in work in technology,

Though the time be an economic boom for the work,

Still the boom shut me out or knocked me out,

And not only in the Church's teaching,

In tale as ancient as Cain and Abel,

Of The Wagon, the Blackbird, and the Saab.

And why I must now accomplish so little,

To pale next to glorious days,

When a-fighting cancer,

I switched discipline to theology,

And first at Cambridge then at Fordham,

Wished to form priests,

But a wish that never came true?

I.

And ere I moped a man appeared, quite short of stature but looking great enough to touch a star. In ancient gold he was clad, yet the golden vestments of a Partiarch were infinitely eclipsed by his Golden Mouth, by a tongue of liquid, living gold. Emblazoned on his bosom were the Greek letters Χ, and Α. I crossed myself thrice, wary of devils, and he crossed himself thrice, and he looked at me with eyes aflame and said, 'Child, hast thou not written, and then outside the bounds of Holy Orthodoxy, a koan?':

A novice said to a master, "I am sick and tired of the immorality that is all around us. There is fornication everywhere, drunkenness and drugs in the inner city, relativism in people’s minds, and do you know where the worst of it is?"

The master said, "Inside your heart."

He spoke again. 'Child, repent of thine own multitude of grievous sins, not the sins of others. Knowest thou not the words, spoken by the great St. Isaac and taken up without the faintest interval by the great St. Seraphim, "Make peace with thyself and ten thousand around thee shall be saved?" Or that if everyone were to repent, Heaven would come to earth?

'Thou seemest on paper to live thy conviction that every human life is a life worth living, but lacking the true strength that is behind that position. Hast thou not read my Treatise to Prove that Nothing Can Injure the Man Who Does Not Harm Himself? How the three children, my son, in a pagan court, with every lechery around them, were graced not to defile themselves in what they ate, but won the moral victory of not bowing to an idol beyond monstrous stature? And the angel bedewed them in external victory after they let all else go in internal and eternal triumph?

'It is possible at all times and every place to find salvation. Now thou knowest that marriage or monasticism is needful; and out of that knowledge you went out to monasteries, to the grand monastery of Holy Cross Hermitage, to Mount Athos itself, and thou couldst not stay. What of it? Before God thou art already a monk. Keep on seeking monasticism, without end, and whether thou crossest the threshold of death a layman or a monk, if thou hast sought monasticism for the rest of thy days, and seekest such repentance as thou canst, who knows if thou mightest appear a monk in lifelong repentance when thou answerest before the Dread Judgement-Throne of Christ?

'Perhaps it is that God has given thee such good things as were lawful for God to give but unlawful and immature for thou to seek for thyself. Thou hast acquired a scholar's knowledge of academic theology, and a heresiologist's formation, but thou writest for the common man. Canst not thou imagine that this may excel such narrow writing, read by so few, in the confines of scholarship? And that as thou hast been graced to walk the long narrow road of affliction, thou art free now to sit in thy parents' splendid house, given a roof when thou art homeless before the law whilst thou seekest monasticism, and writest for as long as thou art able? That wert wrong and immature to seek, sitting under your parents' roof and writing as much as it were wrong and immature to seek years' training in academic theology and heresy and give not a day's tribute to the professorial ascesis of pride and vainglory (thou hadst enough of thine own). Though this be not an issue of morality apart from ascesis, thou knewest the settled judgement that real publication is traditional publication and vanity press is what self-publication is. Yet without knowing, without choosing, without even guessing, thou wert again & time again in the right place, at the right time, amongst the manifold shifts of technology, and now, though thou profitest not in great measure from thy books, yet have ye written many more creative works than thou couldst bogging with editors. Thou knowest far better to say, "Wisdom is justified by her children," of thyself in stead of saying such of God, but none the less thou hadst impact. Yet God hath granted thee the three, unsought and unwanted though thou mayest have found them.'

I stood in silence, all abashed.

Song II.

His Despondency.

The Saint spoke thus:

'What then? How is this man,

A second rich young ruler become?

He who bore not a watch on principle,

Even before he'd scarce more than

Heard of Holy Orthodoxy,

Weareth a watch built to stand out,

Even among later Apple Watches.

He who declined a mobile phone,

Has carried out an iPhone,

And is displeased to accept,

A less fancy phone,

From a state program to provide,

Cell phones to those at poverty.

Up! Out! This will not do,

Not that he hath lost an item of luxury,

But that when it happened, he were sad.

For the rich young ruler lied,

When said he that he had kept,

All commandments from his youth,

For unless he were an idolater,

The loss of possessions itself,

Could not suffice to make him sad.

This man hast lost a cellphone,

And for that alone he grieveth.

Knoweth he not that money maketh not one glad?

Would that he would recall,

The heights from which he hath fallen,

Even from outside the Orthodox Church.'

II.

Then the great Saint said, 'But the time calls for something deeper than lamentation. Art thou not the man who sayedst that we cannot achieve the Holy Grail, nor even find it: for the only game in town is to become the Holy Grail? Not that the Orthodox Church tradeth in such idle romances as Arthurian legend; as late as the nineteenth century, Saint IGNATIUS (Brianchaninov) gaveth warnings against reading novels, which His Eminence KALLISTOS curiously gave embarrassed explanations. Today the warning should be greatly extended to technological entertainment. But I would call thy words to mind none the less, and bid thee to become the Holy Grail. And indeed, when thou thou receivest the Holy Mysteries, thou receivest Christ as thy Lord and Saviour, thou art transformed by the supreme medicine, as thou tastest of the Fount of Immortality?

'Thou wert surprised to learn, and that outside the Orthodox Church, that when the Apostle bade you to put on the whole armour of Christ, the armour of Christ wert not merely armour owned by Christ, or armour given by Christ: it were such armour as God himself wears to war: the prophet Isaiah tells us that the breastplate of righteousness and the helmet of salvation are God's own armour which he weareth to war.

'Thou art asleep, my son and my child; awaken thou thyself! There is silver under the tarnishment that maketh all seem corrupt: take thou what God hath bestowed, rouse and waken thyself, and find the treasure with which thy God hath surrounded thee.'

Song III.

A Clearer Eye.

'We suffer more in imagination than reality,'

Said Seneca the Younger,

Quoted in rediscovery of Stoicism,

That full and ancient philosophy,

Can speak, act, and help today,

Among athletes and business men,

And not only scholars reading dusty tomes.

And if thus much is in a school of mere philosophy,

An individualist pursuit deepenening division,

What of the greatest philosophy in monasticism,

What of the philosophy,

Whose Teacher and God are One and the Same?

I stood amazed at God,

Trying to count my blessings,

Ere quickly I lost count.

III.

Then said I, 'I see much truth in thy words, but my fortunes have not been those of success. I went to Cambridge, with strategy of passing all my classes, and shining brightly on my thesis as I could; the Faculty of Divinity decided two thirds of the way through the year that my promptly declared dissertation topic was unfit for Philosophy of Religion, and made me choose another dissertation topic completely. I received no credit nor recognition for the half of my hardest work. That pales in comparison with Fordham, where I were pushed into informal office as ersatz counselour for my professors' insecurities, and the man in whom I had set my hopes met one gesture of friendship after another with one retaliation after another. Then I returned to the clumsy fit of programming, taken over by Agile models which require something I cannot do: becoming an interchangeable part of a hive mind. I have essayed work in User eXperience, but no work has yet crystallised, and the economy is adverse. What can I rightly expect from here?'

Ere he answered me, 'Whence askest thou the future? It is wondrous. And why speakest thou of thy fortune? Of a troth, no man hath ever had fortune. It were an impossibility.'

I sat a-right, a-listening.

He continued, 'Whilst at Fordham, in incompetent medical care, thou wert stressed to the point of nausea, for weeks on end. Thy worry wert not, "Will I be graced by the noble honourific of Doctor?" though that were far too dear to thee, but, "Will there be a place for me?" And thus far, this hath been in example "We suffer more in imagination than in reality." For though what thou fearest hath happened, what be its sting?

'Thou seekedst a better fit than as a computer programmer, and triedst, and God hath provided other than the success you imagined. What of it? Thou hast remained in the house of thy parents, a shameful thing for a man to seek, but right honourable for God to bestow if thou hast sought sufficiency and independence. Thou knowest that we are reckoned come Judgement on our performance of due diligence and not results achieved: that due diligence often carrieth happy results may be true, but it is nothing to the point. Thou art not only provided for even in this decline; thou hast luxuries that thou needest not.

'There is no such thing as fortune: only an often-mysterious Providence. God has a care each and all over men, and for that matter over stones, and naught that happeneth in the world escapeth God's cunning net. As thou hast quoted the Philokalia:

We ought all of us always to thank God for both the universal and the particular gifts of soul and body that He bestows on us. The universal gifts consist of the four elements and all that comes into being through them, as well as all the marvellous works of God mentioned in the divine Scriptures. The particular gifts consist of all that God has given to each individual. These include:

- Wealth, so that one can perform acts of charity.

- Poverty, so that one can endure it with patience and gratitude.

- Authority, so that one can exercise righteous judgement and establish virtue.

- Obedience and service, so that one can more readily attain salvation of soul.

- Health, so that one can assist those in need and undertake work worthy of God.

- Sickness, so that one may earn the crown of patience.

- Spiritual knowledge and strength, so that one may acquire virtue.

- Weakness and ignorance, so that, turning one's back on worldly things, one may be under obedience in stillness and humility.

- Unsought loss of goods and possessions, so that one may deliberately seek to be saved and may even be helped when incapable of shedding all one's possessions or even of giving alms.

- Ease and prosperity, so that one may voluntarily struggle and suffer to attain the virtues and thus become dispassionate and fit to save other souls.

- Trials and hardship, so that those who cannot eradicate their own will may be saved in spite of themselves, and those capable of joyful endurance may attain perfection.

All these things, even if they are opposed to each other, are nevertheless good when used correctly; but when misused, they are not good, but are harmful for both soul and body.

'And again:

He who wants to be an imitator of Christ, so that he too may be called a son of God, born of the Spirit, must above all bear courageously and patiently the afflictions he encounters, whether these be bodily illnesses, slander and vilification from men, or attacks from the unseen spirits. God in His providence allows souls to be tested by various afflictions of this kind, so that it may be revealed which of them truly loves Him. All the patriarchs, prophets, apostles and martyrs from the beginning of time traversed none other than this narrow road of trial and affliction, and it was by doing this that they fulfilled God's will. 'My son,' says Scripture, 'if you come to serve the Lord, prepare your soul for trial, set your heart straight, and patiently endure' (Ecclus. 2 : 1-2). And elsewhere it is said: 'Accept everything that comes as good, knowing that nothing occurs without God willing it.' Thus the soul that wishes to do God's will must strive above all to acquire patient endurance and hope. For one of the tricks of the devil is to make us listless at times of affliction, so that we give up our hope in the Lord. God never allows a soul that hopes in Him to be so oppressed by trials that it is put to utter confusion. As St Paul writes: 'God is to be trusted not to let us be tried beyond our strength, but with the trial He will provide a way out, so that we are able to bear it (I Cor. 10 : 13). The devil harasses the soul not as much as he wants but as much as God allows him to. Men know what burden may be placed on a mule, what on a donkey, and what on a camel, and load each beast accordingly; and the potter knows how long he must leave pots in the fire, so that they are not cracked by staying in it too long or rendered useless by being taken out of it before they are properly fired. If human understanding extends this far, must not God be much more aware, infinitely more aware, of the degree of trial it is right to impose on each soul, so that it becomes tried and true, fit for the kingdom of heaven?

Hemp, unless it is well beaten, cannot be worked into fine yarn, whilst the more it is beaten and carded the finer and more serviceable it becomes. And a freshly moulded pot that has not been fired is of no use to man. And a child not yet proficient in worldly skills cannot build, plant, sow seed or perform any other worldly task. In a similar manner it often happens through the Lord's goodness that souls, on account of their childlike innocence, participate in divine grace and are filled with the sweetness and repose of the Spirit; but because they have not yet been tested, and have not been tried by the various afflictions of the evil spirits, they are still immature and not yet fit for the kingdom of heaven. As the apostle says: 'If you have not been disciplined you are bastards and not sons' (Heb. 12 : 8). Thus trials and afflictions are laid upon a man in the way that is best for him, so as to make his soul stronger and more mature; and if the soul endures them to the end with hope in the Lord it cannot fail to attain the promised reward of the Spirit and deliverance from the evil passions.

'Thou hast earned scores in math contests, yea even scores of math contests, ranking 7th nationally in the 1989 MathCounts competition. Now thou hast suffered various things and hast not the limelight which thou hadst, or believeth thou hadst, which be much the same thing. Again, what of it? God hath provided for thee, and if thou hast been fruitless in a secular arena, thou seekest virtue, and hast borne some fruit. Moreover thou graspest, in part, virtue that thou knewest not to seek when thou barest the ascesis of a mathematician or a member of the Ultranet. Thou seekest without end that thou mayest become humble, and knowest not that to earnestly seek humility is nobler than being the chiefest among mathematicians in history?

'The new Saint Seraphim, of Viritsa, hath written,

Have you ever thought that everything that concerns you, concerns Me, also? You are precious in my eyes and I love you; for his reason, it is a special joy for Me to train you. When temptations and the opponent [the Evil One] come upon you like a river, I want you to know that This was from Me.

I want you to know that your weakness has need of My strength, and your safety lies in allowing Me to protect you. I want you to know that when you are in difficult conditions, among people who do not understand you, and cast you away, This was from Me.

I am your God, the circumstances of your life are in My hands; you did not end up in your position by chance; this is precisely the position I have appointed for you. Weren’t you asking Me to teach you humility? And there – I placed you precisely in the "school" where they teach this lesson. Your environment, and those who are around you, are performing My will. Do you have financial difficulties and can just barely survive? Know that This was from Me.

I want you to know that I dispose of your money, so take refuge in Me and depend upon Me. I want you to know that My storehouses are inexhaustible, and I am faithful in My promises. Let it never happen that they tell you in your need, "Do not believe in your Lord and God." Have you ever spent the night in suffering? Are you separated from your relatives, from those you love? I allowed this that you would turn to Me, and in Me find consolation and comfort. Did your friend or someone to whom you opened your heart, deceive you? This was from Me.

I allowed this frustration to touch you so that you would learn that your best friend is the Lord. I want you to bring everything to Me and tell Me everything. Did someone slander you? Leave it to Me; be attached to Me so that you can hide from the "contradiction of the nations." I will make your righteousness shine like light and your life like midday noon. Your plans were destroyed? Your soul yielded and you are exhausted? This was from Me.

You made plans and have your own goals; you brought them to Me to bless them. But I want you to leave it all to Me, to direct and guide the circumstances of your life by My hand, because you are the orphan, not the protagonist. Unexpected failures found you and despair overcame your heart, but know That this was from Me.

With tiredness and anxiety I am testing how strong your faith is in My promises and your boldness in prayer for your relatives. Why is it not you who entrusted their cares to My providential love? You must leave them to the protection of My All Pure Mother. Serious illness found you, which may be healed or may be incurable, and has nailed you to your bed. This was from Me.

Because I want you to know Me more deeply, through physical ailment, do not murmur against this trial I have sent you. And do not try to understand My plans for the salvation of people’s souls, but unmurmuringly and humbly bow your head before My goodness. You were dreaming about doing something special for Me and, instead of doing it, you fell into a bed of pain. This was from Me.

Because then you were sunk in your own works and plans and I wouldn’t have been able to draw your thoughts to Me. But I want to teach you the most deep thoughts and My lessons, so that you may serve Me. I want to teach you that you are nothing without Me. Some of my best children are those who, cut off from an active life, learn to use the weapon of ceaseless prayer. You were called unexpectedly to undertake a difficult and responsible position, supported by Me. I have given you these difficulties and as the Lord God I will bless all your works, in all your paths. In everything I, your Lord, will be your guide and teacher. Remember always that every difficulty you come across, every offensive word, every slander and criticism, every obstacle to your works, which could cause frustration and disappointment, This is from Me.

Know and remember always, no matter where you are, That whatsoever hurts will be dulled as soon as you learn In all things, to look at Me. Everything has been sent to you by Me, for the perfection of your soul.

All these things were from Me.

'The doctors have decided that thy consumption of one vital medication is taken to excess, and they are determined to bring it down to an approved level, for thy safety, and for thy safety accept the consequence of thy having a string of hospitalizations and declining health, and have so far taken every pain to protect thee, and will do so even if their care slay thee.

'What of it? Thy purity of conscience is in no manner contingent on what others decide in their dealings with thee. It may be that the change in thy medicaments be less dangerous than it beseemeth thee. It may be unlawful to the utmost degree for thou to seek thine own demise: yet it is full lawful, and possible, for our God and the Author and Finisher of our faith to give thee a life complete and full even if it were cut short to the morrow.

'Never mind that thou seest not what the Lord may provide; thou hast been often enough surprised by the boons God hath granted thee. Thou hast written Repentance, Heaven's Best-Kept Secret, and thou knowest that repentance itself eclipseth the pleasure of sin. Know also that grievous men, and the devil himself, are all ever used by God according to his design, by the God who worketh all for all.

'Know and remember also that happiness comes from within. Stop chasing after external circumstances. External circumstances are but a training ground for God to build strength within. Wittest thou not that thou art a man, and as man art constituted by the image of God? If therefore thou art constituted in the divine image, why lookest thou half to things soulless and dead for thy happiness?'

Song IV.

Virtue Unconquerable.

I know that my Redeemer liveth,

And with my eyes yet shall I see God,

But what a painful road it has been,

What a gesture of friendship has met a knife in my back.

Is there grandeur in me for my fortitude?

I only think so in moments of pride,

With my grandeur only in repentance.

And the circumstances around me,

When I work, have met with a knife in the back.

IV.

The Golden-Mouthed said, 'Child, I know thy pains without your telling, aye, and more besides: Church politics ain't no place for a Saint! Thou knowest how I pursued justice, and regarded not the face of man, drove out slothful servants, and spoke in boldness to the Empress. I paid with my life for the enemies I made in my service. You have a full kitchen's worth of knives in your back: I have an armory! I know well thy pains from within.

'But let us take a step back, far back.

'Happiness is of particular concern to you and to many, and if words in the eighteenth century spoke of "life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness," now there are many people who make the pursuit of happiness all but a full-time occupation.

'In ages past a question of such import would be entrusted to enquiry and dialogue philosophic. So one might argue, in brief, that true happiness is a supreme thing, and God is a supreme thing, and since there can not be two separate supreme essences, happiness and God are the same, a point which could be argued at much greater length and eloquence. And likewise how the happy man is happy not because he is propped up from without, by external circumstance, but has chosen virtue and goodness inside. And many other things.

'But, and this says much of today and its berzerkly grown science, in which the crowning jewel of superstring theory hath abdicated from science's bedrock of experiment, happiness is such a thing as one would naturally approach through psychology, because psychology is, to people of a certain bent, the only conceivable tool to best study to understand men.

'One can always critique some detail, such as the import of what psychology calls "flow" as optimal experience. The founder of positive psychology, Martin Seligman, outlined three versions of the good life: the Pleasant Life, which is the life of pleasure and the shallowest of the three; the Engaged Life, or the life of flow, called optimal experience, and the Meaningful Life, meaning in some wise the life of virtue.

'He says of the Pleasant Life that it is like vanilla ice cream: the first bite tastes delicious, but by the time you reach the fifth or sixth bite, you can't taste it any more. And here is something close to the Orthodox advice that a surplus of pleasures and luxuries, worldly honours and so on, do not make you happy. I tell you that one can be lacking in the most basic necessities and be happy: but let this slide.

'Of the Meaningful Life, it is the deepest of the three, but it is but a first fumbling in the dark of what the Orthodox Church has curated in the light of day. Things like kindness and mercy have built in to the baseline, curated since Christ or rather the Garden of Eden, so Orthodox need not add some extra practice to their faith to obtain kindness or gratitude. Really, the number of things the Orthodox Church has learned about the Meaningful Life far eclipse the Philokalia: the fount is inexhaustible.

'But my chief concern is with the Engaged Life, the life of flow. For flow is not "the psychology of optimal experience," or if it is, the theology of optimal experience hath a different base. Flow is legitimate and it is a wonder: but it is not additionally fit to be a normative baseline for mankind as a whole.

'Flow, as it occurs, is something exotic and obscure. It has been studied in virtuosos who are expert performers in many different domains. Once someone of surpassing talent has something like a decade of performance, it is possible when a man of this superb talent and training is so engrossed in a performance of whatever domain, that sits pretty much at the highest level of performance where essentially the virtuoso's entire attention is absorbed in the performance, and time flies because no attention is left to observe the passage of time or almost any other thing of which most of us are aware when we are awake.

'It seemeth difficult to me to market flow for mass consumption: doing such is nigh unto calling God an elitist, and making the foundation of a happy life all but impossible for the masses. You can be a subjectivist if you like and say that genuis is five thousand hours' practice, but it is trained virtuoso talent and not seniority that even gets you through flow's door. For that matter, it is also well nigh impossible for the few to experience until they have placed years into virtuoso performance in their craft. Where many more are capable of being monastics. Monastics, those of you who are not monastics may rightly surmise, have experiences which monastics call it a disaster to share with you. That may be legitimate, but novices would do well not to expect a stream of uninterrupted exotic experiences, not when they start and perhaps not when they have long since taken monastic vows. A novice who seeth matters in terms of "drudgework" would do well to expect nothing but what the West calls "drudgework" for a long, long time. (And if all goeth well and thou incorporatest other obediences to the diminution of drudgery, thou wilt at first lament the change!) A monastic, if all goes well, will do simple manual labour, but freed from relating to such labour as drudgery: forasmuch as monastics and monastic clergy recall "novices' obediences", it is with nostalgia, as a yoke that is unusually easy and a burden unusually light.

'And there is a similitude between the ancient monastic obedience that was par excellence the bread and butter of monastic manual labour, and the modern obedience. For in ancient times monks wove baskets to earn their keep, and in modern times monks craft incense. And do not say that the modern obedience is nobler, for if anything you sense a temptation, and a humbler obedience is perhaps to be preferred.

'But in basket making or incense making alike, there is a repetitive manual labour. There are, of course, any number of other manual obediences in a monastery today. However, when monasticism has leeway, its choice seems to be in favour of a repetitive manual labour that gives the hands a regular cycle of motion whilst the heart is left free for the Jesus Prayer, and the mind in the heart practices a monk's watchfulness or nipsis, an observer role that traineth thee to notice and put out temptations when they are a barely noticeable spark, rather than heedlessly letting the first temptation grow towards acts of sin and waiting until thy room be afire before fightest thou the blaze. This watchfulness is the best optimal experience the Orthodox Church gives us in which to abide, and 'tis no accident that the full and unabridged title of the Philokalia is The Philokalia of the Niptic Fathers. If either of these simple manual endeavours is unfamiliar or makes the performer back up in thought, this is a growing pain, not the intended long-term effect. And what is proposed is proposed to everybody in monasticism and really God-honoured marriage too, in force now that the Philokalia hath come in full blossom among Orthodox in the world, that optimum experience is for everyone, including sinners seeking the haven of monasticism, and not something exotic for very few.